The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (43 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Justinian II, still only twenty-four, took vengeance on the traitorous Bulgarians by massacring their wives and children. But his army was inclined to blame him, not the mercenaries. In 695, the officers rebelled against him, took him captive, and mutilated him by cutting off his nose, slitting his tongue, and sending him in chains to Cherson, the fortress where military prisoners languished. They acclaimed one of their own generals, Leontios, as emperor in his place.

With Leontios at the helm the empire suffered the final loss of Carthage, its complete occupation by Arab forces, and the end of eight hundred years of Roman settlement in North Africa. The caliph al-Malik appointed an Arabic governor named Musa bin Nusair to rule the new Muslim province, Ifriqiya. And back in Constantinople, the general Leontios suffered the wages of defeat and was in turn overthrown. In 698, he was taken prisoner, mutilated, and sent to a monastery, and the army chose another soldier as emperor.

15

By 702, the Islamic conquest of North Africa was nearly complete. The Berbers, the native North Africans, converted in remarkable numbers. Their tribal structure made conversion a mass event rather than an individual decision; when the leaders of a tribe converted, the rest of the tribe followed.

The Arabic realm itself was beginning to cohere a little more tightly under al-Malik’s expert administration. He had already introduced standard currency; he put his brothers, whom he trusted, into the most vital governors’ offices; and he began to construct a new mosque in Jerusalem that would provide a place of worship and pilgrimage even more central than the Ka’aba in Mecca (although Mecca retained its importance). This mosque, the Dome of the Rock, was built on the site of the destroyed Second Temple of the Jews;

*

it protected the rock from which Muhammad was said to have ascended into heaven.

Al-Malik also decreed that the Arabic language would be the official language of the empire, something no previous caliph had done. This provided a desperately needed glue for the widely scattered realm. Islam and the Arabic language were the two constants throughout the lands of the Arab conquests; Christianity and Latin had parted ways somewhat, as the Franks and Visigoths and Lombards and Greeks translated the texts of their religion into their own tongue, but Islam and Arabic (and Islam and Arabic culture) would remain tied closely together.

Between 661 and 714, the heavenly sovereigns of Japan decree a Great Reform, issue a code of law, and write a legendary history

T

HE TIDAL WASH

and ebb of attacking and retreating armies had shaped the internal politics of almost every medieval nation but Japan. On their jagged islands, protected on the west by sea and on the east by a vast expanse of ocean, the heavenly sovereigns ruled: the borders of their power nebulous, making little attempt to conquer themselves an empire by force, their attention fixed firmly on home ground.

But although Tang warships did not dock at the harbors of the Yamato rulers, the Tang were nevertheless invading, by a slow and insidious infiltration of ideas.

After her second spell on the throne, Heavenly Sovereign Saimei died in 661, leaving the Yamato crown to her son. Naka no Oe finally stood at the top of the pyramid of power, with his long-time ally Nakatomi no Kamatari as his right-hand man. But for nearly seven years after his mother’s death, Naka no Oe continued to govern as crown prince and regent. Not until 668 did he finally claim the rightful title of heavenly sovereign and the imperial name Tenji. He was forty-two years old; he had spent twenty-three years waiting for the stain of Soga blood to fade from his hands before reaching for the sceptre.

Not long after his formal accession, he rewarded Nakatomi no Kamatari’s lifelong loyalty by giving him a new name: Fujiwara. By this act, he made his friend the patriarch of a new clan, founder of a new family. The Fujiwara clan would rise steadily in power, eventually reaching a height of influence greater than that of the broken-backed Soga.

Tenji’s disastrous plunge into foreign politics—his attempt to help Baekje’s king regain the throne had ended with a shattering defeat of the Japanese army by the Tang-Silla alliance—had merely reinforced the natural Yamato tendency to focus on the home front. As crown prince, and with the help of Nakatomi no Kamatari, he had already written and tried to put into place a whole series of reforms intended to transform the Yamato domain—still a linked series of clans, dominated by clan leaders who jealously guarded their own authority—into a single royal realm, governed without dispute by a single monarch. The new sweeping decrees were called the Great Reform, or the “Taika reforms.” By legal fiat, all of the Yamato domain was declared to be a single public realm, held by the crown on behalf of the people. Private estates and hereditary clan rights over them were abolished. So was the old system of titles. “Let the following be abolished,” the first Reform Edict declared: “private titles to lands and workers held by ministers and functionaries of the court, by local nobles, and by village chiefs.”

1

Instead of owning their land and claiming the titles of nobility, the former clan leaders and village chiefs would be

granted

the right to govern the land, which now essentially belonged to the Yamato ruler. And instead of claiming their noble titles, they would be awarded ranks that positioned them in a newly formed bureaucracy.

The Great Reform was not invented by the Yamato; it came over the water from China. Naka no Oe had sent scores of scholars and priests over to the Tang, to learn the long history of the Chinese emperorship, to study the structures of Tang government, and to bring back what they learned. The world that the Great Reform attempted to create is modelled after the ancient Chinese map of the world, a set of concentric rings with the emperor’s power all-encompassing at the center and executed by proxy at the distant edges; in places, the edicts of the Great Reform quote, word for word, from the Chinese histories that Naka no Oe’s emissaries brought back from their travels. The centuries of disorder in Luoyang and Nanjing made little difference. The Chinese emperors could claim—fairly or not—to belong to a tradition of royal authority that flowed down from the beginnings of time, and the Yamato aspired to join the ancient stream.

2

As Heavenly Sovereign Tenji, the former Naka no Oe now set himself to create a court in which he would stand—like the emperors of China—not merely as warleader and chief general (a position vulnerable to the fortunes of war), but as representative of an entire culture, leader of civilization, guarantor of cosmic order. Historian Joan Piggott, borrowing the term from Confucius, calls this “polestar monarchy” the sovereign, says the

Analects

, “exercises government by means of his virtue and thus may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it.” In his effort to become the orienting point of Japanese culture, Heavenly Sovereign Tenji brought historians and poets to his court and founded a university. He and his court read the Chinese classics, which had arrived in the hands of a travelling Buddhist monk in 660. He led his court in celebrating Chinese rites that linked heavenly order to earthly tranquillity.

3

According to his biographers, Heavenly Sovereign Tenji also ordered his ministers to collect the laws of Japan into a written legal code, distinct from the Great Reforms. Japan, filled with discrete communities, with a heavenly sovereign whose rule was largely theoretical rather than hands-on in many of its parts, had existed without a legal code for a long time. But partly due to the contact with Tang China and United Silla, partly due to Tenji’s sense that a heavenly sovereign should have a little more power on earth, it was time for written laws.

This code does not seem to have ever been completed. Whatever work was done on it stalled when Heavenly Sovereign Tenji became ill after a mere four years of official rule. The illness caused him severe unrelieved pain in his last days and hours. Finally, the atonement for Soga no Iruka’s death was complete.

4

Tenji’s grandson Mommu became heavenly sovereign in 697; the fourteen-year-old boy continued the task that Tenji had begun, and in 701 issued the first surviving set of laws from Japan. The

Taiho ritsu-ryo

, or Great Treasure, enfolded the legal work Tenji had begun within it. It outlined a thoroughly well-controlled country, one where authority was laid out in an elaborate series of branching bureaucracies, each with its own set of ranks and offices.

5

It was a beautifully structured set of laws, and the world it envisioned was just as orderly as the concentric rings of authority laid out in the edicts of the Great Reform. But despite several royal generations of intense borrowing, the Tang-inspired decrees had a stronger existence on paper than in reality. The Tang template had been laid over the Japanese islands, but beneath the template vast swathes of the country ran along just as they had before. The clan leaders might hold bureaucratic ranks instead of noble titles, but they exercised the same authority; the land might belong to the crown in name, but it was still farmed and divided, plowed and shaped, by the same men who had owned it before the reforms.

Not long after issuing his legal code, Mommu died at the age of twenty-five and was succeeded on the throne by his mother. Gemmei, daughter of the heavenly sovereign Tenji, was the fifth woman to sit on the throne within a matter of decades—a preponderance of female rulers almost unknown elsewhere in the medieval world. Like the tip of an ancient pyramid, the heavenly sovereign touched the divine and connected it to the people at the base. Whether a man or woman occupied that position at the pyramid’s tip was relatively unimportant. In the culture of the Tang Chinese, where trade routes and food supplies lay under the emperor’s purview, only a woman unusually talented at administration and people management could convince her court that she was worthy of their loyalty. But Gemmei was not a Tang monarch, despite her court’s adoption of all those Tang customs; and she could act as the polestar of her people, regardless of her gender.

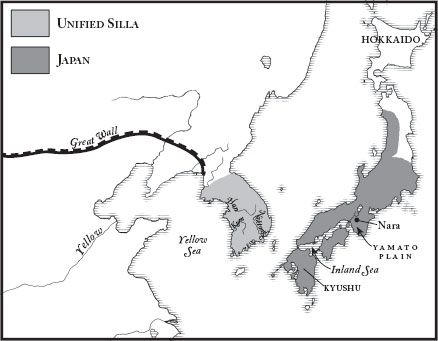

43.1: The Nara Period

In the third month of her reign, Gemmei announced that her capital would be at Nara, a city to which Heavenly Sovereign Mommu had intended to move, before his plans were cut short by death. Until this point, the capital city of the Yamato rulers had been moveable; each ruler declared his or her residence to be the new center of government. But Gemmei’s new capital was an innovation. The city, which was known to her as Heijo, the City of Peace, would remain the capital for the next eighty years (the “Nara period” of Japan). She also had new plans drawn up for its enlargement and glorification, plans modelled (naturally) on the layout of the Tang capital of Chang’an. The glories of Chang’an had deeply impressed the Japanese visitors to the capital city.

6

In the past, the dwelling place of the heavenly sovereign had been a minor matter because the sovereign was a locus of heavenly power, not earthly power. There was no need for earthly power to accrue in a physical place, no sense that a stone Senate building, a royal court, or even a throne was necessary to connect the heavenly sovereign’s rule to the earth. But over the next decades, as the ruler remained at Nara, she would gain a slightly less tenuous connection with the political establishment. The polestar would not merely shine; it would reach meddlesome hands into earthly matters.

At the same time, the polestar would claim greater and greater divinity. Gemmei abdicated in 714 in favor of her daughter, Heavenly Sovereign Gensho, and in the middle of her nine-year reign, Gensho presided over the publication of the Yoro Code. The Code put into words an idea that had been growing in popularity: that the heavenly sovereign not only touched the divine but was herself godlike. The polestar did not relay heavenly illumination. It was the source.

7

During the rule of the next heavenly sovereign, Gensho’s younger brother Shomu, a new foundation was carefully built underneath the shaky, already erected structure of Japanese royal privilege. For a Yamato king, Shomu ruled in “unprecedented grandeur,” with an elaborate court, a rabbit-warren of bureaucrats, and all the trappings of full kingship. And he commissioned something that was, so far, missing: an ancient past for the Yamato kings. During his reign, the first mythical histories of Japanese kingship, the

Kojiki

and the

Nihon shoki

, were written.

8

According to these accounts, the first Yamato king had been the grandson of the sea god and the great-great-grandson of the sun goddess. With the blood of both sea and sky running in his veins, the boy Jimmu rose to rule his people. As a grown man, he gathered his sons together and gave them a charter. Long ago, he told them, the world had been “given over to widespread desolation,” to darkness, disorder, and gloom. But then the gods had given man a gift—the leadership of the imperial house. Under the heavenly sovereign, darkness and chaos had given way to beauty and order, and the land had become a place of fertility and light, good crops and peaceful days and nights. “But the remote regions do not yet enjoy the blessings of Imperial rule,” he told them. “Every town has always been allowed to have its lord, and every village its chief, who, each one for himself, makes division of territory and practices mutual aggression and conflict…. [Those lands] will undoubtedly be suitable for the extension of the heavenly task, so that its glory should fill the universe. Why should we not proceed there?” And so they did, marching behind the god-king on their way to drive out chaos and darkness.

9

It had become vital to lay a myth-foundation for Japanese kingship, even if that myth-foundation had to be partially constructed out of nothing. The histories of Japanese kingship created a past full of righteous warfare and divine approval, and that past was carefully thrust underneath the present. It re-created Yamato Japan as a country founded on heroism, legendary feats of strength, and the favor of the gods.