The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (20 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

As the first abbot of Monte Cassino, Benedict was the ruler that Italy lacked: devoted to a calling higher than his own ambitions, offering a law that was the same for all and was enforced with absolute justice and regularity, providing a clear and straightforward path into happiness. The Benedictine way of life provided the monks with unity, with an identity as members of a community they themselves constituted. And it was, above all,

orderly

. “You who hasten to the heavenly country,” the Rule concluded, “perform with Christ’s aid this Rule, which is written down as the least of beginnings: and then at length, under God’s protection, you will come to the greater things that we have mentioned; to the heights of learning and virtue.” Learning and virtue had once been prized in Rome, but now they led nowhere; only in the Benedictine monastery did the exercise of the mind and the discipline of the spirit yield great reward.

14

Between 471 and 518, the Persians object to social reform, Slavs and Bulgars appear, and the Blues and Greens fight in Constantinople

P

ERSIA WAS SUFFERING

, and in 471 the suffering was compounded when the Persian king led the empire into war.

Yazdegerd II had died in 457, and his oldest son, Peroz, had taken the throne after a brief struggle with his brothers. Peroz’s twenty-seven-year reign was a difficult one; Persia suffered from a severe famine and, according to the eyewitness account attributed to the eastern monk Joshua the Stylite, locusts, earthquake, plague, and a solar eclipse.

1

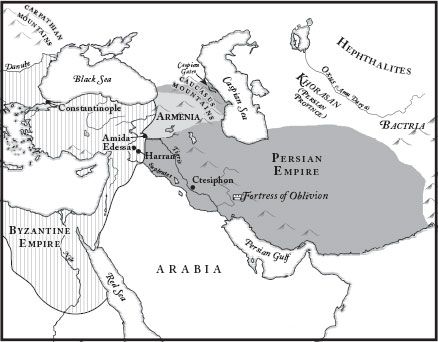

On the heels of the famine came war with the Hephthalites, the same peoples who had straggled down across the Kush mountains to cause trouble for the Gupta kings of India. They had settled into a kingdom on the eastern side of the Persian empire, but Peroz quarrelled repeatedly with the Hephthalite king over the boundary between their lands.

In 471 he finally marched an army into Hephthalite territory. The Hephthalites retreated in front of them, craftily, and then circled around behind and trapped the Persian army. Peroz was forced to surrender, swear an oath that he would never attack again, and retreat. He also agreed to pay the Hephthalites an enormous tribute, so large that it took him two years to raise it from his people. Meanwhile his oldest son, Kavadh, spent two years at the Hephthalite court as a hostage, a guarantee that the money—thirty mules loaded with silver, according to Joshua the Stylite—would eventually be handed over.

2

Peroz finally managed to tax the tribute out of his people, and Kavadh returned home. But the defeat simmered in the mind of the Persian king until he could no longer bear it. In 484 he assembled an even greater army and invaded Hephthalite land once more.

Again he was tricked. Procopius says that the Hephthalites dug a pit and covered it over with reeds sprinkled with earth, and then withdrew beyond it to set up their battle line; al-Tabari adds that the Hephthalite king stuck the treaty that Peroz had signed, promising not to invade Hephthalite territory again, on the tip of his spear. The Persians, thundering forward into battle, fell into the pit—horses, lances, and all. Peroz himself was killed “and the whole Persian army with him.” It was a shattering defeat, perhaps the worst in the history of Sassanid Persia. The Hephthalites, who up until this point had remained on the eastern side of the Oxus river, now took control of Khorasan (the Persian province on the western side), and the Persians “became subject and tributary to the Hephthalites.” Peroz’s body, crushed by the twisted mass of men and horses in the battlefield trench, was never recovered.

3

Back at the Persian capital Ctesiphon, Peroz’s son and heir, Kavadh, was driven out by Peroz’s brother, Balash. The brief civil war that followed was complicated by the fact that the Persian treasury was empty. Balash sent ambassadors to Constantinople to ask for Roman help, but none appeared. Unable to fight on multiple fronts, he agreed to put an end to the ongoing problem of Armenia by signing a treaty that gave the Armenians independence to run their own affairs.

*

Meanwhile Kavadh, like Aetius before him, took advantage of the friendships he had formed as a hostage and went to the Hephthalites for help. It took him several years to talk their king into assisting him, but in 488 he was finally able to claim the Persian throne as his own.

4

Which introduced a brand new complication into Persian attempts to recover from the ill-advised wars with the Hephthalites. Rather than being a follower of the orthodox Zoroastrian religion, Kavadh I was a disciple of a heretical cult led by a Persian prophet named Mazdak. Zoroastrianism, like Christianity, believed that good would ultimately triumph; the Christian savior would return to earth to destroy evil and make all things right, while the Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda would wipe out his evil competitor, Ahriman, renew the earth, and raise the dead so that they could walk upon it in perfect bliss.

5

But Mazdak, like the Christian gnostics, taught that the ultimate power in the universe was a distant and uninvolved deity, and that two lesser but equal divine powers, good and evil, struggled over the universe. Men had to align themselves with the good power and reject the evil, choosing light over darkness. Different gnostic religions suggested various ways in which that might be done; Mazdak believed that the primary way of finding the light was to get rid of human suffering by making all men (and to some degree women) equal. He preached that men should share their resources equally, no one owning private property to the detriment of others; that competition be replaced by equality, strife by brother love. Unlike Christian gnosticism, Mazdakism worked itself out as social justice.

6

22.1: Persia and the Hephthalites

Kavadh I began to reform his country in line with Mazdak’s ideas. The laws he passed puzzled his contemporaries so deeply that some interpretation is necessary if we are to figure out exactly what he intended. Al-Tabari says that he intended “to take from the rich for the poor and give to those possessing little out of the share of those possessing much,” while Procopius writes that Kavadh wanted the Persians to have “communal intercourse with their women.” It is highly improbable that Kavadh I was trying to institute full communism in Persia, but it is very likely indeed that he was attempting to redistribute some of the wealth held by the powerful Persian nobles (this would have reduced their power and influence, which could have only helped Kavadh I), and that he lifted some of the oppressive restrictions that forced women to marry men of their own class and allowed them to be shut up in the harems of wealthy noblemen.

7

The Persian nobles naturally resented the curtailment of their privileges, and Kavadh’s social reforms ended in 496 when the aristocrats of his court removed him by force and put his brother Zamasb on the throne of Persia. Zamasb refused to murder anyone who shared his bloodline, and so Kavadh was hauled away to southern Persia, to a prison called the Fortress of Oblivion. “For if anyone is cast into it,” Procopius writes, “the law permits no mention of him to be made thereafter, but death is the penalty for the man who speaks his name.”

8

While Zamasb rolled back his brother’s reforms, Kavadh languished in the Fortress of Oblivion for two years. Finally, he managed to make his escape. Al-Tabari says that Kavadh’s sister sprung him out of prison by getting visiting privileges (through sleeping with the fortress’s warden), rolling Kavadh up in a carpet, and having the carpet carried out; Procopius says that the woman who slept with the warden was Kavadh’s wife, and that once she had earned the privilege of seeing her husband, the two switched clothes and Kavadh made his escape under cover of a woman’s robe.

9

Either way, Kavadh made his way to the land of the Hephthalites, where he once again pled for help in regaining his throne. The Hephthalite king not only agreed but also gave Kavadh his own daughter as a wife to seal the bargain. Kavadh marched back to Ctesiphon at the head of a Hephthalite army. The Persian soldiers fled as soon as they saw their opponents, and Kavadh broke into the palace, blinded his brother with a hot iron needle, and imprisoned him.

His second possession of the throne lasted over thirty years, but there was no more flirting with communism and no further attempts to level the Persian playing field through social-justice legislation. He could rule only with the support of the Persian noblemen, and with the help of the soldiers they supplied, and this placed a limit on his power.

What he could do, however, was fight the eastern Romans, and in 502 he declared war on the Roman emperor Anastasius.

Zeno the Isaurian died without a son in 491; a month after his death, his widow married Anastasius, a minor but devout court official who became the new emperor of the eastern Romans. He was undistinguished both in peace and in war, and his most notable feature was a mismatched pair of eyes, one black and one blue, which earned him the nickname “The Two-Eyed.”

10

His attempts to fight off Kavadh were inept and futile. The Persians sacked the Roman half of Armenia and laid siege to the border city of Amida, a siege that went on for eighty days while Kavadh’s Arab allies, under the Arab king Na’man of al-Hirah, ranged farther south and sacked the territory around Harran and Edessa. Finally the Persians took Amida; Procopius says that they broke in when the Christian monks who had been given the defense of one of the towers had a religious festival, ate and drank too much, and went to sleep. Once inside the city, they massacred the population—eighty thousand people, according to Joshua the Stylite, who adds that they piled the bodies in two huge heaps outside the city so that the smell of decomposing corpses wouldn’t choke the Persian occupiers.

11

The conquest of Amida would probably have been followed by many more Persian triumphs had Kavadh not found himself dealing with another Hephthalite invasion on his other border; his alliance by marriage had not produced a permanent peace with the eastern enemies. He found himself fighting on two fronts, and although the Persian army continued to devastate the land on the eastern Roman border, by 506 the two empires were ready to negotiate a treaty.

The war was over. Not much had been accomplished, except that the Romans had lost a little more than they had gained. The treaty gave Amida back to the Romans, but the Persians remained in control of their most important conquest: just before peace negotiations opened, they had taken control of the narrow path through the Caucasus Mountains, known to the ancients as the Caspian Gates. The king who controlled the Gates had power to open or close the south to invaders from the north.

12

T

HE

P

ERSIAN INVASION

was only one of Anastasius’s problems. New peoples had appeared on the western border of his empire and were causing unending troubles.

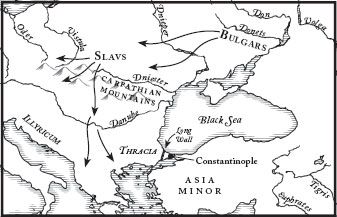

The initial threat came from the Slavs, tribes that were moving south and west towards the eastern Roman borders. The Slavs came from north of the Danube, but they weren’t “Germanic”—a name the Romans had applied indiscriminately to anyone from the northern territories. Imprecise though the term was, the Germanic peoples had spoken languages with a common source, which linguists have reconstructed in the form of “Proto-Germanic”—a hypothetical ancestral tongue. This suggests some sort of shared origin, too far back in time to be located with any certainty, but more than likely the far-distant origin of the Germanic peoples was northern European. The Slavic tribes came from farther east, between the Vistula and Dnieper rivers, and belonged to a different language family.

*

It isn’t always easy to figure out exactly which tribes referred to by ancient historians belong to the Slavic rather than the Germanic language group, but both Jordanes and Procopius describe peoples who seem to be Slavs coming from the Carpathian Mountains, north of the Danube. They were taking up residence in the Danube river valley and threatening to overflow down into the old Roman provinces of Thracia and Illyricum.

†

22.2: Troubles West of Byzantium

Anastasius dealt with the problem by exiling the Isaurians, who had shown a tendency to rebel, from their homeland and settling them instead in Thracia. This had the double effect of weakening their sense of national identity and providing him with a barrier against the Slavs. To survive in their new country, the Isaurians had to fight off the Slavs.

The Slavic invasion was joined by yet another influx of wanderers: the Bulgars. They were from central Asia, from the same land as the Huns, and they were governed by khans. The bulk of the Bulgar tribes (not yet coalesced into any kind of a kingdom) were still east of the Slavs, but trailing after them to the west; the later

Russian Primary Chronicle

says that they followed the Slavs into their territory and “oppressed” them there. They crossed the Danube in 499, fought, raided, and then returned back over the river, “gorged with plunder and crowned with the glory of a victory over a Roman army.” They invaded again in 502, stealing and destroying.

13