The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (19 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Ricimer, who was in Milan, heard of the witch hunt with exasperation. He recalled six thousand soldiers from the North African front, marched into Rome, and in 472 defeated Anthemius and put him to death.

The marriage had not saved Anthemius, but Ricimer did not survive much past his father-in-law. He had barely arrived in Rome when he came down with a fever. Two months later, Ricimer was dead.

Without its puppet-master, the empire stumbled even more fatally. Anthemius was followed by four emperors in four years, none of them managing to assert any kind of real power. Finally another barbarian soldier stepped forward to take control. His name was Orestes, and he had already emerged once at a turning point of Roman history: he had been the Roman-born ambassador sent from Attila the Hun to Constantinople back in 449.

After the Hun disintegration he had returned to serve in the western Roman army and had gained an increasing following. In 475, with the title of Roman emperor held by the useless Julius Nepos, Orestes rallied his troops behind him, hired a collection of Germanic mercenaries from various tribes, and marched on Ravenna. Julius Nepos fled without putting up a fight. Rather than taking the throne himself (the myth that Roman emperors were not barbarians had been exposed, but still lived), Orestes appointed his own ten-year-old son, Romulus, to the imperial throne. Romulus, the child of Orestes and his fully Roman wife, was less barbarian by blood than the father.

The court at Ravenna was willing to accept this fiction, which kept the Roman title alive for one more year. Romulus—given the patronizing nickname “Augustulus,” meaning “little Augustus,” by his subjects—sat on the throne for a single year while the western empire fell apart around him.

In 476, even the fiction failed. Orestes had promised to pay his Germanic mercenaries by giving them land in Italy to settle on. Now their leader, the general Odovacer—a German and a Christian—demanded more land for his followers. Orestes refused, and in the hot days of August, Odovacer and the mercenaries marched toward Ravenna, seeking payment and revenge. Orestes met him in battle at Placentia, in northern Italy. The Roman forces were defeated; Orestes was killed in the fighting.

Odovacer went on to Ravenna unopposed, took little Romulus prisoner, and sent him to live in a castle in Campania: Castel dell’Ovo, a fortress on an island reached only by a causeway. There he spent the rest of his days in obscurity. “Thus the Western Empire of the Roman race,” says Jordanes, “which Octavianus Augustus, the first of the Augusti, began to govern in the seven hundred and ninth year from the founding of the city, perished…and from this time onward kings of the Goths held Rome and Italy.”

14

The old western empire, with its stubborn insistence that Romans must rule in Roman land, was no more.

But the death warrant for the western empire had been signed by Constantine over a century before, when he had decided that

Romanness

alone could hold the empire together. Odovacer’s rise to the throne of Italy was merely the final admission of what had already happened: the barbarians had given up on the project of becoming Roman. Italy was largely Christian; Odovacer was a Christian. He took the title “King of Italy,” separating himself from the old imperial past. He was a competent soldier, and a decent administrator; and as far as his supporters were concerned, his blood no longer mattered.

Between 457 and 493, the Isaurians ascend to the eastern throne, the Ostrogoths take control of Italy, and the Benedictines retreat

I

N

457,

THE EASTERN

Roman emperor Marcian died at the age of sixty-five. His wife, Pulcheria, had died four years earlier. The Theodosian dynasty that had ruled in Constantinople since 379 had ended.

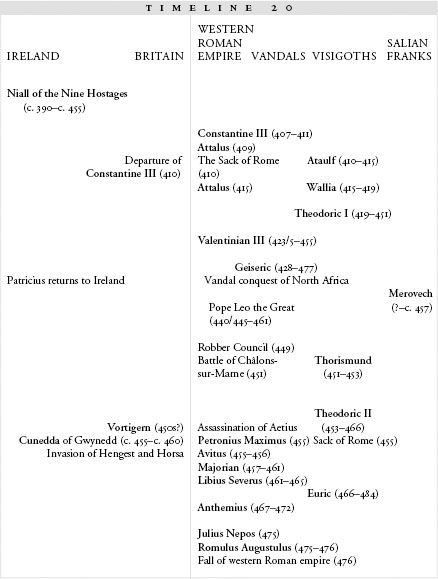

*

As there was no blood heir available, the army had the greatest say in who would become emperor next. Their commanding general would normally have been a top candidate, but in 457 the army was commanded by a man of barbarian descent: Aspar, who belonged to a tribe known as the Alans (they had once lived east of the Black Sea and had been driven from their own lands by the Huns decades earlier). The eastern empire, still calling itself Roman, clung to its old suspicion of barbarian blood: Aspar could no more become emperor of the eastern Roman realm than the Vandal Stilicho or the Visigoth Ricimer could have become emperor in the west.

Instead, Aspar chose the agreeable fiftyish steward of his household, Leo the Thracian, to be his voice-piece. Leo was crowned emperor by the patriarch of Constantinople—the first time the bishop had taken on this pope-like role in the east.

But once on the throne, Leo the Thracian proved impossible to manipulate. Aspar had the loyalty of the army, so in order to reduce his general’s influence, Leo made a new series of alliances with the Isaurians, a mountain people of southern Asia Minor. The Isaurians had been under Roman rule for five hundred years, but they had remained warlike and free-acting, carrying on their own affairs almost independently on the slopes of the Taurus Mountains. They had the advantages of barbarians—the skill at war, the self-directed purpose—without the disadvantages; they were, thanks to the centuries that had passed since their incorporation into the empire, undisputably Roman.

Leo, who had no sons (another reason why Aspar had fingered him for the job of emperor), made a match between his daughter Ariadne and the Isaurian leader Zeno. With the Isaurians behind him, he accused Aspar of treachery and, in 471, executed him.

1

Three years later, the elderly emperor died of dysentery. His daughter’s six-year-old son, Leo II, was crowned as emperor in his place. Leo II’s father, the Isaurian warrior Zeno, served as his regent. The child ruled for ten months, rubber-stamped his father’s coronation as co-emperor, and then died, leaving the Isaurian on the throne of the eastern Roman empire.

This was a dizzying rise to power for the Isaurians, and it created temporary unrest in Constantinople; Leo the Thracian’s brother-in-law managed to raise an army against Zeno and drive him out of the city. The brother-in-law, Basiliscus, then crowned himself emperor. Thanks to his policies of heavy taxation, though, Basiliscus made himself unpopular; meanwhile Zeno had gone home and assembled an Isaurian army of his own, which he marched back into Constantinople eighteen months later. The financially strapped population greeted him with relief, and Basiliscus deserted his throne and fled to a nearby church. Zeno, standing outside the church, got Basiliscus out by promising that he would not shed the usurper’s blood; when Basiliscus emerged, Zeno then shut him up in a dry cistern and let him starve to death.

2

Firmly back in power by 476, Zeno the Isaurian watched from the east as the remnants of the western Roman empire spun apart. Odovacer, the Germanic general who had just removed little Romulus from the throne, was now king of Italy. He had taken Ravenna by force; Jordanes says that his initial strategy was to “inspire a fear of himself among the Romans.”

3

But there was a limit to how long he could rule over the larger territory of Italy through terror. To bolster his claim to power, Odovacer sent a message to Zeno suggesting a new strategy: he would acknowledge Zeno as overlord and emperor, and would rule Italy in submission to the eastern empire, if Zeno would in turn recognize him as rightful ruler of Italy.

Zeno accepted the offer and gave Odovacer the title of patrician (not king) of Italy. It was a titular reunification: for a brief time, under Zeno the Isaurian, the empire was again one. But Odovacer, having obtained a legitimacy that made his mastery of the Romans in Italy a little easier, went on to ignore Zeno and do exactly as he pleased. In 477, he conquered Sicily, which had been in the hands of the Vandals; the great Vandal king Geiseric had just died, and the Vandal kingdom declined in power without his leadership. He made treaties, just like an independent king, with the Visigoths (who now ruled a kingdom that stretched from the Loire all the way across Hispania) and with the Franks.

4

By 488, Zeno was seriously worried about Odovacer’s growing ambition.

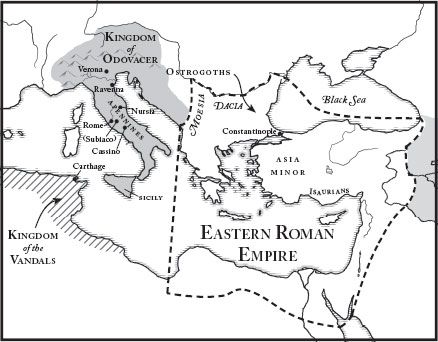

21.1: Odovacer’s Kingdom

Zeno also had another western problem to solve. A coalition of Ostrogoths was moving from their lands in the west eastwards, towards Constantinople. They were led by a soldier named Theoderic, son of a Gothic chief who had spent ten years as a child in Constantinople, a hostage guaranteeing the good behavior of his father. At eighteen, he had returned to his people and become their leader—which meant that he had the task of finding them more land. The Ostrogoths had too many people and not enough space; they were hungry and overcrowded.

*

Between 478 and 488, the Ostrogoths under Theoderic advanced steadily towards Constantinople, claiming food and territory as they went. Zeno tried to appease Theoderic with the title of

magister militum

, awarded him land in the regions of Dacia and Moesia, and even paid him a substantial amount of money when Theoderic threatened to besiege Constantinople itself in 486. But none of these solutions had pacified the Ostrogoths for long.

5

Zeno decided to solve the two problems simultaneously: he offered to recognize Theoderic the Ostrogoth as king of Italy and give him the peninsula, as long as Theoderic would go west and get rid of Odovacer. The sources disagree about who first came up with this plan, Theoderic or Zeno, but whoever thought it up, Theoderic liked it. He headed west, marching at the head of a heterogeneous mass of adventurers: Ostrogoths, random Huns, discontented Romans, displaced members of other Germanic tribes. The Gaulish writer Ennodius, who was a child at the time, writes that a “whole world” followed Theoderic to Italy—perhaps as many as a hundred thousand people, in search of a country.

6

When they marched into northern Italy, Odovacer tried to resist; he assembled an army on the plain of Verona to block the path of the invaders, but Theoderic destroyed it “with great slaughter” and stormed towards Ravenna.

The fight over Italy went on for three years. Jordanes says that Odovacer spent most of those three years holed up in Ravenna: “He frequently harassed the army of the Goths at night,” he writes, “sallying forth with his men…and thus he struggled.” Ravenna grew increasingly shabby and hungry. Finally, in 491, Odovacer suggested a compromise. He would sign a treaty making the two of them co-rulers of Italy if Theoderic would lift the siege.

Theoderic had found the siege frustrating; Odovacer could resupply the city by sea, and Theoderic, with no fleet, couldn’t stop him. He agreed to the compromise, but in 493 he ended their joint rule by killing his colleague. The contemporary account of Valensianus says that the Ostrogoth king hewed his co-ruler in two “with his own hands, boasting that his suspicions were at last confirmed—Odovacer had no backbone.”

7

Unlike Odovacer, Theoderic had a spine. He was not interested in being a “patrician” and paying lip service to Constantinople. He was now Theoderic the Great, king of Italy, and as king he had no duty to pay the eastern Roman emperor.

One of his first acts was to declare that only the Romans who had supported him in his takeover of Italy could still claim to be Roman citizens; the rest were deprived of their rights. Roman citizenship, that once-prized distinction, was now connected directly to the person of Theoderic the Great.

8

U

NDER

T

HEODERIC’S RULE

, the prestige of Rome, once queen of the world, faded away. Theoderic visited Rome only once, in the year 500, and never bothered to go back. The Senate still met in Rome, but the power of law lay with the king, and ultimately the Senate rubber-stamped his rule.

Roman culture made inroads into Gothic practice; the Goths increasingly spoke Latin, adopted Roman names, married Roman women, and cultivated Roman estates. But while Romans held many of the civil offices in Theoderic’s government, high

military

posts were held almost exclusively by Goths. Boys were sent to Rome to study grammar and rhetoric, but Ravenna, dominated by Goths, was the power center of the kingdom.

9

The conflict between the two races came sharply to the fore when Theoderic died in 526. His heir, his ten-year-old son Athalaric, became the pawn in a struggle for power between his mother Amalasuntha (who served as his regent) and the Ostrogoth nobles who wanted to control the kingdom from behind the throne. Amalasuntha wanted to send her son to school in Rome, to receive the sort of education that “Roman princes” received. The Goths objected that a Roman education would make him a sissy. Procopius writes, “For letters, they said, are far removed from manliness, and the teaching of old men results for the most part in a cowardly and submissive spirit. Therefore the man who is to show daring…ought to be freed from the timidity which teachers inspire and to take his training in arms.” Apparently Theoderic himself, careful though he was to keep the Romans and Goths in his empire on more or less equal footing, had nurtured misgivings of his own over the value of a Roman education: the Goths claimed that he “would never allow any of the Goths to send their children to school; for he used to say that, if the fear of the strap once came over them, they would never have the resolution to despise sword or spear.” Clearly, a literary education in Rome was not the high road to power and influence it had once been, and the lifestyle of young men studying in the once capital grew increasingly dissolute and aimless.

10

One of the young men sent to school in Rome was Benedict of Nursia, son of a Roman nobleman. Like Augustine, he dabbled in the less respectable pastimes available to him; but finally he grew exasperated with the noise and licentiousness of the city, gave up his studies (which weren’t providing him with advantage in any case), and left.

According to Gregory the Great, who provides us with the only early account of Benedict’s life, he ended up in a cave in the Apennines about forty miles east of Rome, near the modern town of Subiaco. At some point he had heard the teachings of Christianity and had been converted; now he devoted himself to the lifestyle of a pious hermit, seeking to understand the grace of God in solitude. News of the hermit in the wilderness spread, and several years later monks in a nearby monastery asked him to come and take charge of their community, since their abbot had just died.

Benedict agreed. His chaotic years in Rome and his solitary meditation had given him a vision for community life that was regulated, quiet, and productive: “Having now taken upon him the charge of the Abbey,” says Gregory the Great, “he took order that regular life should be observed, so that none of them could, as before they used, through unlawful acts decline from the path of holy conversation, either on the one side or on the other.” The monks, unused to such strict supervision, decided to poison his wine; but Benedict got wind of the plan and went back to his cave. There he taught the shepherds who came to see him, converting a number of them to the monastic lifestyle.

11

Around 529, he led them up a mountain near the town of Cassino. On the mountaintop, an old temple of Apollo had been slowly decaying into ruins. Benedict and his monks burned it and in its place began to build a monastery of their own.

In this monastery, Monte Cassino, Benedict developed the rules by which his community would live: the Rule of St. Benedict. The Rule was the

lex

of a kingdom removed from the political struggles, a conscious attempt to bring Christian practice back to the realm where the Indian and Chinese monks dwelt. “We desire to dwell in the tabernacle of God’s kingdom,” Benedict wrote, “and if we fulfill the duties of tenants, we shall be heirs of the kingdom of heaven.”

12

He listed those duties: to relieve the poor, clothe the naked, visit the sick, bury the dead, to prefer nothing to the love of Christ. In daily life, silence was preferable to speech, since words so often led to sin; the monks, rising regularly during the night to sing psalms, were to sleep clothed so that they would always be prepared for worship and service; the abbot was to consult the monks over decisions that affected the whole community, but in the end his decisions were final; the “vice of personal ownership” was to be “cut out in the monastery by the very root,” so that monks were to own nothing, not even books or writing materials; each monk was to spend a prescribed number of hours per day in manual labor; any monk who persisted in breaking the Rule was to be barred from eating with the community or taking part in worship until he repented. Gregory the Great reports that the “spirit of prophecy” allowed Benedict to know when the monks were breaking the Rule even when they were away from the monastery; when they returned, he would tell them their faults. They repented, and “would not any more in his absence presume to do any such thing, seeing they now perceived that he was present with them in spirit.”

13