The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (18 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Between 454 and 476, the Vandals sack Rome, and the last emperor leaves Ravenna

A

ETIUS HAD NOT ANSWERED

Vortigern’s plea for help because he had troubles of his own.

Sentiment against his domination of the western empire had been growing, and the Hun invasion of Italy had given him a black eye. He had powerful enemies at court—most notably Petronius Maximus, a Roman senator who had been prefect of Rome twice. In 454, Aetius made a final misstep when he arranged the engagement of his son to Valentinian III’s daughter. It was a clear attempt to put his family in line for the western throne.

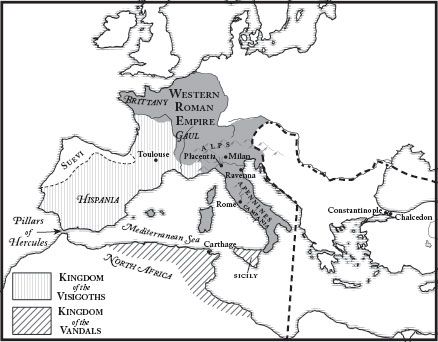

Valentinian III, still only thirty-six, had been emperor of Rome for thirty years but had always ruled in the shadow of his general. He had lost much of his empire; Hispania and much of Gaul were gone to the Suevi and the Visigoths, and North Africa to the Vandals, who under their great king Geiseric had already taken Sicily and were eyeing Italy itself. Huns had stormed through Italy almost without check, and the bishop of Rome had done Valentinian’s job while he cowered. It was easy for Petronius Maximus to convince the emperor to focus his discontent on Aetius. “The affairs of the western Romans were in confusion,” writes the historian John of Antioch, “and Maximus…persuaded the emperor that unless he quickly slew Aetius, he would be slain by him.”

1

In 455, Valentinian III was in Ravenna when Aetius came to court on a routine visit to discuss tax collection. He was standing in front of Valentinian III, absorbed in presenting the difficulties of raising money, when Valentinian III leaped up from his seat, shouting that he would no longer put up with treachery, and swung his sword against Aetius’s head. The great general died on the floor of the throne room while the stunned courtiers watched.

John of Antioch says that Valentinian then turned in satisfaction to one of his officers and said, “Was not the death of Aetius well accomplished?” The officer answered, “Whether well or not I do not know, but I do know that you have cut off your right hand with your left.” And so it proved. In killing the man who prevented him from claiming full power, Valentinian had destroyed his only chances of retaining any power at all. Just weeks later, Petronius Maximus convinced two old army cronies of Aetius’s to assassinate the emperor as he practiced archery in the Campus Martius. They stole the dead man’s crown, and fled with it to Petronius Maximus—who took it and declared himself emperor.

2

20.1: The Collapse of the Western Roman Empire

Thus began a seven-year cycle of death and destruction. Petronius Maximus tried to head off the Vandals by sending the retired prefect of Gaul, a native of Gaul named Avitus who was living peacefully on his own Gaulish estates, to negotiate an alliance with the Visigoth king at Toulouse. But Avitus had not yet returned with Visigoth allies when Geiseric and his Vandals landed their ships on the shores of southern Italy.

The news was greeted in Rome with panic and riots. Petronius Maximus, seeing the mood of the city grow increasingly ugly, tried to leave, but he was riding away from the walls when a rock thrown by a rioter struck and killed him. Rome was without an emperor and without a general. Three days after Maximus’s death, on April 22 of 455, the Vandals arrived at the city and broke through the gates.

3

For fourteen days, the North African barbarians roved through the city, plundering and wrecking so thoroughly that their name became a new verb: to “vandalize,” to ruin without purpose. In fact, the plundering had a very definite purpose. Geiseric did not intend to try to hold the city. He wanted its wealth, and the Vandals did a thorough job of stealing all the gold and silver of Rome—even tearing the gold plating off the roof of the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus.

The intercession of the pope, Leo the Great, prevented the burning of the city and the large-scale massacre of the people, but even Leo could not prevent Geiseric from kidnapping Valentinian’s widow and his two teenage daughters. The Vandals returned to Carthage with the three women and ships full of treasure; one ship, loaded with statues, sank and is still in the Mediterranean mud somewhere, but the others reached North Africa safely. Geiseric then married his son Honoric to the older of the two girls, Eudocia (the same daughter Aetius had chosen for his own son), and sent the other two women, with his compliments, to Constantinople.

4

In Constantinople, the new eastern Roman emperor, Marcian, welcomed Valentinian’s family, but he refused to send eastern Roman soldiers west to avenge the sack of Rome. He had sworn, more than twenty years earlier, never again to fight against the Vandals; it had been a condition of his release after he had been taken prisoner at the capture of Carthage by Geiseric and his invading army.

When the news of Petronius Maximus’s death and the sack of Rome arrived in Toulouse, where the Gaulish ambassador Avitus was still negotiating with the Visigoths, the Visigoth king Theodoric II suggested that Avitus declare

himself

emperor. He offered his own Visigoth forces as allies. Avitus accepted and marched south across the Alps, entering Rome in triumph as the third emperor to rule within the year.

By this point, Rome was robbed, wrecked, and hungry. Avitus found himself grappling with a city devastated by famine and plunder. There was so little food that he was forced to send the Visigothic allies away, since there was no way to feed them. First, though, he had to pay them, and since there was no money left in the treasury, he stripped all the remaining bronze off the public buildings and handed it over to them.

5

This infuriated the people of Rome, who were in a mood to be infuriated by any offense, and Avitus’s attempts to rule failed in less than a year. He had appointed as his

magister militum

a half-German general named Ricimer, who had fought under Aetius as a young man. While Avitus was trying to pacify Rome, Ricimer was off south driving the remaining Vandals back from the Italian coast. This made him enormously well liked, in inverse proportion to Avitus’s plummeting popularity. In 456, when Avitus finally fled from the city of Rome in fear for his life, heading back to his estates in Gaul, Ricimer met him on the road and took him prisoner. The early historians disagree on what happened next, but it appears that Ricimer kept him under guard for some months, after which Avitus died of unknown causes.

Ricimer was now the most powerful man in Rome, but he knew that his barbarian ancestry would prevent the Roman Senate from confirming his rule as emperor. So he prepared to appoint a colleague—the soldier Majorian, who now became the western emperor in name and Ricimer’s puppet in reality.

Majorian served, usefully, as Ricimer’s public face, which meant that Ricimer could shift the blame for failure onto his shoulders. In 460, Majorian and the western Roman army gathered on the coast of Hispania (thanks to the friendship of the Visigoths) with three hundred ships, preparing to attack the Vandal kingdom in North Africa. Procopius writes that the ships assembled at the Pillars of Hercules, the entrance to the Mediterranean, planning to “cross over the strait at that point, and then to march by land from there against Carthage.” Geiseric began to prepare for a massive war; the people of Italy, expecting victory, got ready to celebrate.

6

A sneak attack cut the invasion short. The ships, says the chronicler Hydatius, were suddenly seized from the shore “by Vandals who had been given information by traitors.”

7

Some behind-the-scene plot, either carried out with the connivance of the Visigoths or done with the help of someone in the western Roman army, had thoroughly sabotaged the plan.

Majorian began to march from Hispania back towards Italy in disgrace. In the foothills of the Apennines, Ricimer’s men waylaid and beheaded him. In his place, Ricimer chose Libius Severus, who became the next emperor of the western Roman empire.

8

No one seems to have recorded much of anything that Severus did. He was simply another one of Ricimer’s faces, and he only remained in place for four years. In 465, he died in Rome, either of sickness or of poison, and for eighteen months Ricimer did not bother to push for the appointment of another emperor. The idea of a legitimate Roman emperor in the west was suddenly revealed for what it was: a myth which helped the Romans pretend that a disintegrating realm, now consisting of little more than the peninsula of Italy, still had some vital connection with the glory of the past; a useful fiction which disguised the truth that to be Roman and to be barbarian were now one and the same.

Finally, in 467, Ricimer roused himself to appoint a new emperor, not because he needed one but because he found it useful in facing his current problem: the Visigoths. In 466, Theodoric II of the Visigoths had been murdered by his brother Euric, who took up the Visigothic flag and started storming around Gaul with it. He was rapidly expanding his reign over land that had once been Roman, and Ricimer needed to fight back. The Visigoths had once been a useful ally; now they were a menace.

9

But Ricimer did not intend to start an actual war without the figurehead of an emperor to lead it. So in 467 he proposed to the Senate that the Roman general Anthemius, who happened to be married to the daughter of the eastern emperor Marcian, become the new

imperator

.

Anthemius, who was no fool, suggested that Ricimer marry his own daughter Alypia to create an extra layer of loyalty. The marriage was celebrated late in 467, just as the poet Sidonius Apollinaris was arriving in Rome: “My arrival coincided with the marriage of the patrician Ricimer,” he wrote to a friend, “to whom the hand of the Emperor’s daughter was being accorded in the hope of securer times for the State.”

Though the bride has been given away, though the bridegroom has put off his wreath, the consular his palm-broidered robe, the brideswoman her wedding gown, the distinguished senator his toga, and the plain man his cloak, yet the noise of the great gathering has not died away in the palace chambers, because the bride still delays to start for her husband’s house.

10

Apparently Alypia was not pleased with the marriage; Ricimer was now a soldier in his sixties, fifteen years older than her own father.

T

OGETHER

, R

ICIMER

and the new emperor Anthemius prepared for war against the Visigoths.

The Visigoths had provided the Romans with soldiers to fight against the Vandals; now the two men looked around for soldiers who could help them fight against the Visigoths. They found a new alliance in the northwestern corner of Gaul. There, a Briton named Riotimus had settled with some twelve thousand men; they were tired of the ongoing battle between the British and the Angles and Saxons and had crossed the channel to find peace.

11

But peace was hard to come by in the lands of the old empire. Riotimus knew that the spread of Visigothic power threatened his new home, which had become known as Brittany. He agreed to supply twelve thousand men for the fight against the Visigoths, but the Visigothic king Euric did not give the reinforcements time to join up with the main body of the Roman army. “He came against the Brittones with an innumerable army,” Jordanes says, “and after a long fight he routed Riotimus, king of the Brittones, before the Romans could join him.”

12

The fight against the Visigoths had failed almost before it began, and the Visigothic kingdom in Hispania spread still farther. Meanwhile Roman soldiers continued fighting fruitlessly against the Vandals in North Africa. Nothing was going well, and when Anthemius got sick in 470, he decided that his ill fortune had been caused by black magic. He “punished many men involved in this crime,” writes John of Antioch, even though the crime itself was unproven sorcery, and started putting men to death.

13

20.1: Castel dell’Ovo, where the last Roman emperor lived out his days.

Credit: Photo by Davide Cherubini