The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (14 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

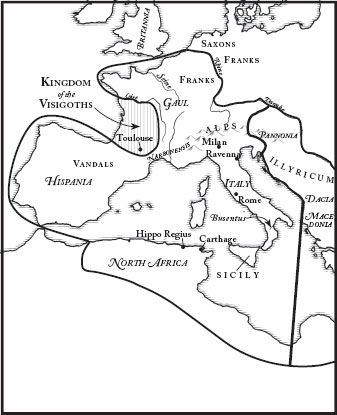

Between 410 and 418, the Visigoths settle in southwestern Gaul

W

ITH

R

OME BEHIND THEM

, Alaric and his Visigoth army headed south to attack Africa, taking their loot and their captives with them.

It was a short journey. Jordanes tells us that a sudden fierce storm wrecked the ships as they sailed from Sicily, forcing the Visigoths to retreat back into southern Italy. Alaric was deciding on his next course of action when he was struck by illness and suddenly died. His men diverted the path of the nearby river Busentus and “led a band of captives into the midst of its bed to dig out a place for his grave. In the depths of this pit they buried Alaric, together with many treasures, and then turned the waters back into their channel. And that none might ever know the place, they put to death all the diggers.” The first king of the Visigoths had never gained the recognition he spent most of his life seeking, but at least he received a hero’s burial.

1

The Visigoth Ataulf became king in his place. Not long after Alaric’s death, Ataulf married Placida, in a formal ceremony in a small city in northern Italy (the Visigoths had apparently given up their plan of crossing over to North Africa). He was, says Jordanes, “attracted by her nobility, beauty, and chaste purity.” Whether this was a romance of captor and captive or a political move, the result was the same: “the Empire and the Goths,” Jordanes concludes, “now seemed to be made one.” Alaric’s lifetime of fighting had failed either to overcome that persistent Roman identity or to merge his own with it; Ataulf’s marriage, blending Visigoth blood with Roman, accomplished much more in a single stroke.

2

Once married, Ataulf decided that Gaul would provide easier pickings than either southern Italy or North Africa. Gaul was in turmoil. It had been in the hands of the British pretender Constantine III, and while Ataulf was getting married in north Italy, the western emperor Honorius was sending an army over the Alps to get Gaul back. The reconquest succeeded almost at once. Constantine III’s soldiers, once in Gaul, had begun to desert him in favor of life in the countryside; his weakened troops fled in the face of the Roman soldiers, and Constantine III ran to the nearest church and had himself ordained as a priest.

3

This blatant attempt to shield himself with the cross was only temporarily successful. Alaric had refused to burn the churches of Rome, and Honorius (the nonbarbarian) could do no less. He spared Constantine III’s life and instead took him prisoner. While he was being brought back to Rome, however, an assassin murdered him, and his accomplices were, as Jordanes puts it, “unexpectedly slain.” The supposed unity between fellow Christians was not strong enough to save the life of a challenger to the imperial throne.

4

Ataulf’s Visigoths inserted themselves into the middle of Gaul while Honorius was busy with Constantine III. By 413, they had conquered land in the old Roman territory of Narbonensis, in southern Gaul, and Ataulf had made the city of Toulouse into the capital of a small Visigothic kingdom. He had finally found a possible homeland for Alaric’s nation.

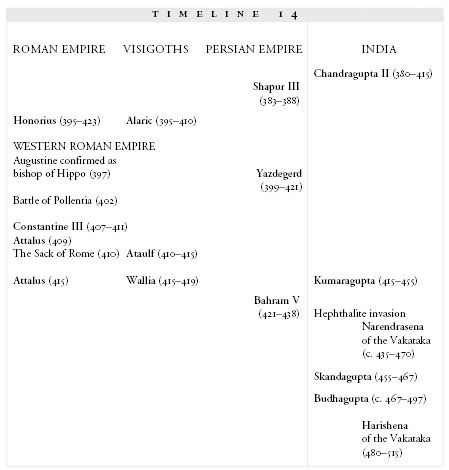

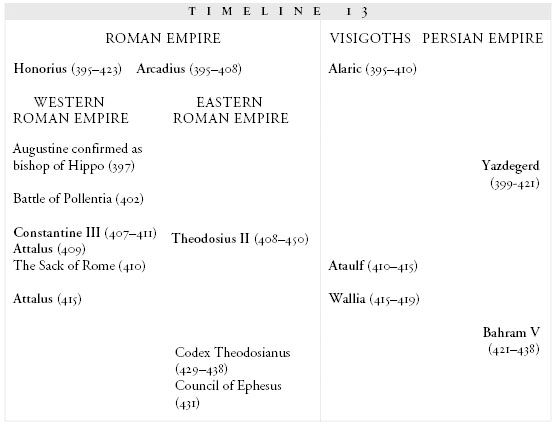

13.1: Visigoth Kingdom

But rather than establishing his kingdom as a Visigothic nation, Ataulf returned to the seductive idea of Roman rule. His marriage to Placida had given him visions of a world in which he controlled not just the ragtag Visigoths but the empire itself. He hoped, says the historian Orosius, to “seek for himself the glory of completely restoring and increasing the Roman name by the forces of the Goths, and to be held by posterity as the author of the restoration of Rome, since he had been unable to be its transformer.”

5

Attalus, the ex-emperor that Alaric had created and then stripped of his title, had been trailing around in the Visigothic army ever since. Now, Ataulf again crowned him, setting him up once more as a rival emperor to Honorius.

He would have done better to throw himself into building up the Visigoths. Honorius sent his right-hand general and

magister militum

, the Roman-born Constantius, against the new emperor. Constantius’s army harassed the Visigoths, eventually capturing and beheading Attalus and reducing Ataulf’s newborn kingdom to hunger and desperation. Resentment against Ataulf began to simmer among his own people. In 415, one of his own countrymen murdered him and claimed the position of Visigoth king, only to be killed in turn seven days later by another Visigoth warleader named Wallia.

6

Wallia retrenched and sent word to Constantius that he was willing to make a deal. He would help the western Roman army in Hispania to fight against a coalition of Germanic tribes who had made their way onto the peninsula; and he would send Honorius’s sister Placida, the young hostage Aetius (now nineteen), and the other captives taken in Rome, five years earlier, back to Ravenna. In exchange, he wanted southwestern Gaul for the Visigoths.

Honorius agreed to the treaty. After nearly two decades of wandering, the Visigoths finally had a homeland.

The freed captives were soon put back into the service of the state. In 417, two years after her return to Ravenna, Placida was ordered by her brother to marry his general Constantius, the man who had driven her first husband, Ataulf, into desperation and death. We do not know what she said; we do know that she obeyed him. And in 418, Honorius sent Aetius off in another hostage exchange. The Huns, still hovering on the distant edges of the known world, had agreed to make a temporary peace. The treaty demanded that both sides provide guarantees of goodwill by sending young men to live at the enemy court. Honorius offered the Huns Aetius, who had been home for only a short time. In return, the Huns sent a relative of the Hun warleader Rua: Rua’s nephew, a twelve-year-old boy named Attila.

Between 415 and 480, the Gupta empire fades away, while Theravada Buddhism encourages the pursuit of individual enlightenment

W

HEN THE

I

NDIAN KING

Chandragupta II died in 415, he left behind him an empire of internal contradictions. It was modelled on the ancient glories of Asoka but built on the armed conquests that Asoka had renounced. Sanskrit, the moribund language of nomadic invaders, had become its language of sophistication and education. It boasted a huge expanse, but in much of its territory the king ruled in name only.

To complicate these internal contradictions, an outside threat arose. During the thirty-nine-year reign of his son and successor Kumaragupta, the Hephthalites began to straggle down across the Kush mountains.

The Hephthalites were nomads from the wide steppes of central Asia. The Indians called them

hunas

, not because they were related to Huns in the west, but because the Indians used the general name “Huns” for all roaming nomadic groups north of the mountains.

*

Rather, the Hephthalites were most likely a branch of the Turkic peoples: Asian tribes that had long ago shared a common language, and began to spread out from their homeland in central Asia during the fifth century. They had been fighting off and on with the Persians for forty years already; the Armenian historian Faustos of Byzantium says that Shapur III fought against “the great king of the Kushans,” his term for the Hephthalites.

1

Roman historians say that the Hephthalites were quite different from other nomadic invaders: “They are ruled by one king,” Procopius writes, “and have a lawful government and deal in an upright and just way with each other and with their neighbors, just like Romans and Persians.” Later Arab geographers, putting the history of the Persians into the context of their own holy books, record a genealogical tradition that the Hephthalites were descended from Shem, the son of Noah. But as far as the peoples of north India were concerned, they were simply

mleccha

, speakers of other tongues—barbarians in the classical sense.

2

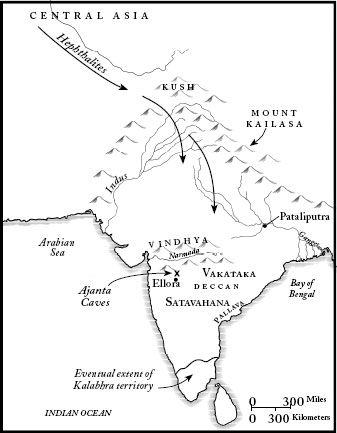

14.1: Invasion of the Hephthalites

Kumaragupta drove them back, preserving the Gupta domain for the time being. Details of his other accomplishments are scarce, but one royal inscription boasts that his fame “tasted the waters of the four oceans.” Another inscription lays out the extent of his empire. By 436, it stretched from Mount Kailasa on the north, to the forests on the slopes of the Vindhya Mountains in the south, and was bordered by the oceans on the east and west. This was the largest area that the Guptas ever claimed for their own; Kumaragupta brought the empire to its peak. Legends of his reign reflect his real conquests. He was “lord of the earth,” with the “valour of a lion” and the “strength of a tiger,” the “Moon in the firmament of the Gupta dynasty.”

3

But the end of his reign seems to have been clouded by troubles. Inscriptions mention fighting in the region called “Mekala”—the land of the Vakataka in the western Deccan, the peoples that Chandragupta II had folded into the Gupta empire by marriage. The new king of the Vakataka was Kumaragupta’s own great-nephew, Narendrasena; he came into his throne at just about the time that Kumaragupta was at the height of his power. But despite his great-uncle’s fame, Narendrasena rebelled.

4

The fighting seems to have taken place just as Kumaragupta was occupied with the Hephthalite invasions, and so Narendrasena was able to assert his independence.

From this point on, the Gupta fortunes began to decline. A hostile invasion came next: it is not completely clear who the invaders were, but a stone pillar inscription says that they “had great resources in men and money” and “threatened the Gupta kingdom with utter ruin.” The fight against them, led by Kumaragupta’s son and heir Skandagupta, was long and difficult. At one point Skandagupta was so bereft of men and supplies that he had to spend the night on the bare ground of a battlefield.

5

Ultimately, the inscriptions tell us, the Guptas won the war against the invaders. But all was not well in the empire. Coins from the last years of Kumaragupta’s reign are no longer made from silver or gold; instead they are made of copper, with a thin coating of silver concealing the inferior metal. The royal treasury had been thoroughly drained.

When Kumaragupta died in 455, Skandagupta inherited his troubles. He beat the Hephthalites off once again: “He destroyed at its roots the pride of his enemies,” his victory inscription reads. But the battles had taken a heavy toll. In the years after Skandagupta’s accession, events become increasingly muddled, but a hazy picture of increasing disorder emerges: poverty, quarrelling officials, rebellions of warlords and minor kings at the edges of the empire, constant war. Skandagupta fought for his entire reign, managing to keep the empire from disintegrating; through most of the 460s, victory inscriptions continue to appear throughout the old Gupta territory.

6

The last of these inscriptions dates to 467. After that, the evidence is confused. It seems likely that Skandagupta died in this year and a war over the throne broke out, adding internal chaos to the chaos on the outside. First Skandagupta’s brother and then a nephew claimed the throne. Ultimately the victor was a second nephew, Budhagupta. He held onto the Gupta throne for thirty years, but he was the last Gupta king to rule over anything that resembled an empire.

The Gupta attempt to hold together an empire of the mind had lasted only as long as no external threat approached. The Hephthalite attacks during the reigns of Kumaragupta and Skandagupta were serious, but they were hardly civilization-ending and not nearly as overwhelming as the Hun threat in the west. But turning to answer even a medium-sized crisis from the outside had strained the empire’s cohesiveness to its limits. With the king’s attention elsewhere, the states around the empire’s edges—states that were receiving no real benefit from being part of the Gupta empire—immediately seized on the opportunity to declare themselves once again free.

In fact, it seems to have been the nature of Indian kingdoms to organize themselves as relatively small, independent entities with shifting borders. In the south, where the Gupta reach never extended, a multiplicity of dynasties claimed dominance over different parts of the subcontinent. Inscriptions and coins give us dozens of royal names, but no clear story emerges from the southern jostle. Towards the end of Budhagupta’s reign, there was no political power that seemed capable of uniting even a small part of the subcontinent.

I

T WAS A LOW TIME

for empires, but a flourishing time for religion. Buddhist monuments known as “stupas” spread across the country, many carved with scenes of worshippers. In the west of India, a series of temples and monasteries were carved into natural chambers, with pillars and prayer rooms, corridors and staircases, rock-hollowed great halls for the use of those who pursued knowledge rather than political power. They were modelled after wooden buildings, with stone rafters and ribs upholding the domed ceilings sculpted into the rock. The largest series of these temples, the thirty or so caves known as the Ajanta Caves, had already been under construction for the last three hundred years, and work on them would continue for three hundred more.

7

Twelve simpler caves had already been built in Ellora, barely fifty miles south. In this part of India, the Vakataka dominated, and the Vakataka king Harishena celebrated his victories by sponsoring the construction of at least two of these caves. Harishena, rising to the throne around 480 and overlapping the reign of Budhagupta to the north, had acquired a brief empire of his own, but his fleeting kingdom would not outlast his death.

8

The intersection between Harishena’s victories and the cave-temples was an aberration. Most of the caves were excavated simply to provide a place for worship, not to commemorate conquests. They had absolutely nothing to do with politics, and neither did the men who lived there.

Among the cave-temples were other networks of carved rooms: the

viharas

, monasteries complete with individual cells, common rooms, and refectories. Here the monks could devote themselves to the practice of their beliefs without distraction. They did not go into isolation; they lived in community themselves, and since they relied on lay people for clothing and food (items they could not acquire since they had renounced money), they also stayed in touch with the locals. But they took no part in the doings of the empire.

9

By this time, Buddhism had branched into two major schools: the Theravada school and the Mahayana school. Both taught that all physical things were transient, and that only enlightenment—a “state of mind reached through moral conduct and meditation”—could reveal the world for what it is, an impermanent and unreal place. Theravada Buddhism, dominant in India, taught that reasoning, mindfulness, and concentration would lead the mind to enlightenment; in slight contrast, Mahayana Buddhism, which tended to dominate the Chinese experience, stressed prayer, faith, divine revelation, emotion.

10

With its greater emphasis on reasoning and thought, Theravada Buddhism placed a higher value on the monastic existence, which allowed the believer to put all of his energies into study and meditation. Certainly Theravada Buddhism gave no help to an army officer or minor king who wanted to conquer an empire. It was diametrically opposed to earthly conquest, and rather than binding its adherents together under one flag, it encouraged them to live side by side while seeking individual enlightenment.

Which is exactly what the landscape of India in the fifth century reflected. Perhaps Theravada Buddhism helped to produce the patchwork profile of India; or perhaps the Indian patchwork made the country particularly suited to Theravada Buddhism. Either way, the result was the same. All across the Indian countryside, kingdoms existed side by side: each pursuing its own individual goals, none of them dominating the rest.