The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (12 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

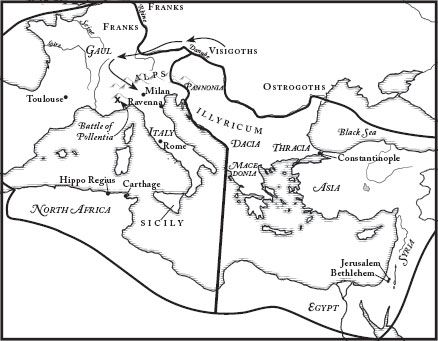

Between 396 and 410, the North African province rebels, the emperor of the west retreats to Ravenna, and the Visigoths plunder Rome

F

OR THE

R

OMAN CITIZENS

on the North African coast, crosscurrents in authority were nothing new. For centuries they had lived under the double authority of the distant emperor and of his local representative, the Roman provincial governor. North Africa was far from Rome; it was not uncommon for the governor to pay lip service to the emperor while doing the opposite of the emperor’s orders.

In 396, while Stilicho and Eutropius were jousting over control of the empire, a new bishop was appointed to watch over the Christian church in the busy coastal city of Hippo Regius. Augustine was a native African, born into Roman citizenship and trained at Roman schools in Carthage. His struggle to explain the nature of the divided authority he lived under would provide an imaginative picture of the world so strong that the entire Christian church—and, eventually, the kings of the western world—would grasp hold of it.

In his twenties, Augustine had lived in Rome as a teacher of rhetoric; in his thirties, he lived in Milan, where the bishop Ambrose became his friend and advisor. For most of this time Augustine was a Manichee, a follower of the religion established by the Persian prophet Mani more than a century before. Manichaeism taught that the universe was made up of two powerful forces, Good and Evil, which were eternally opposed; that matter was intrinsically Evil; and that human beings could only return to the Good by withdrawing from as much contact with matter as possible.

1

After listening to Ambrose, though, Augustine rejected his Manichee past and, after some thought, decided to become a catechumen (a student) of Nicene Christianity. His new training threw him into increasing uncertainty and distress; one day, as he sat in a garden in Milan, weeping over the misery in his soul, he heard a child’s voice chanting, “Pick up and read, pick up and read.” This he interpreted as a command to pick up St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, which lay nearby. When he read from it, he was instantly converted to belief in Christ: “A light of relief from all anxiety flooded into my heart,” he wrote in his autobiography, the

Confessions

. “All the shadows of doubt were dispelled.”

2

He went back home and took up a career in the church. But the North African church to which he returned had been almost ripped apart by a dispute peculiar to it. Rather than arguing about the nature of Christ, the North African Christians were struggling with a question that had to do with the nature of his church.

The dispute was rooted in the persecutions by Diocletian, a hundred years before. Diocletian had executed Christians all across the empire, but down in North Africa the local Roman governor hadn’t thrown himself behind the persecution. Instead, he told the local clergy that if Christians would just hand over their Scriptures as a symbol of recantation, they could go about their business.

3

Some did; others refused. When the persecution was over, the Christians who had rejected the governor’s offer were incensed to find that one of the priests who

had

turned over his Scriptures to the authorities was about to be made bishop of Carthage. They insisted that any baptisms administered by this man would be a sham, and that his bishopric would contaminate the entire Christian church.

4

The protesting North African Christians, who became known as Donatists, after their leader Donatus Magnus, believed that the church was a place where the grace of God was conveyed to believers through holy men. For the Donatists, baptisms were effective and Eucharists were real only when the priest who administered them was himself a holy man. “What perversity must it be,” asked the Donatist leader Petilianus, “that he who is guilty through his own sins should make another free from guilt?”

5

To this, Augustine replied, “No man can make his neighbor free from sin, because he is not God.” His answer reflected the official position of the bishop of Rome: the church was a place where the grace of God was conveyed to believers because God willed it to be so, not because of the character of the men who occupied its official positions. The Donatists were the first

puritan

Christians, the first to insist that the church was supposed to be a gathering of holy and righteous people, and that the unrighteous and unworthy should be purged from its midst; against them, the orthodox,

catholic

thinkers of the church argued that it was impossible (and just plain wrong) for men to attempt to purify the church of God.

6

Augustine, forced by the Donatists to define the church, wrote that the church on earth would always be a “mixed body,” true believers and hypocrites temporarily united in a single group. “The Church declares itself to be at present both,” he concluded, “and this because the good fish and the bad are for the time mixed up in the one net.” It was not for man to separate the good and bad; only at the end of time, when Christ returned and all things were set right, would the frauds be winnowed out.

7

This was not a minor problem. It was a major difference, and from the North African turmoil would eventually spring inquisitions and heresy trials and English Puritans. And although the question was a theological one, it was not unaffected by politics. In a time of chaos, when what it meant to be a Roman was increasingly unclear, the Donatists insisted on creating an identity they could control and a community that was thoroughly well defined—without ambiguity, without uncertainty.

The political chaos only worsened over the next years. In 397, the North African province revolted. The leader of the revolt was Gildo, the Comes Africae—the officer in charge of the defense of the Roman territory in North Africa. Since North Africa was part of the western Roman empire, it belonged under the control of the young emperor Honorius and his guardian Stilicho. But the eunuch Eutropius, Stilicho’s enemy and the power behind the eastern throne of the young emperor Arcadius, had convinced Gildo to repudiate his loyalty to Honorius. “He annexed it [instead] to the empire of Arcadius,” writes Zosimus, “[and] Stilicho was in extreme displeasure at this, and knew not what course to pursue.”

8

The rebellion caused an immediate problem for Stilicho because the fertile fields of North Africa were the primary supplier of grain to the western part of the empire. Gildo’s first move was to hold up the shipments of corn headed for Rome, which very quickly reduced the population of the city to hunger. In response, Stilicho convinced the Senate to declare a war against Gildo. Five thousand Roman soldiers, under the command of Gildo’s own brother Mascezel, sailed to Africa to meet Gildo and his seventy thousand men. Mascezel had more than Rome to avenge; Gildo had murdered his two sons, Gildo’s own nephews.

What could have been a bloodbath of Roman troops turned into a travesty. Mascezel, meeting one of Gildo’s standard-bearers, slashed at the bearer’s arm with his sword; the bearer dropped the standard, upon which all of Gildo’s standard-bearers down the line assumed that surrender had been called and lowered their standards as well. The soldiers behind them surrendered at once. Mascezel declared victory with barely a death on either side. Gildo tried to flee, but when his ship was shoved back to African shores by the wind, he killed himself.

In declaring Stilicho an enemy of the east, Eutropius had won round one of the battle for power; now Stilicho, reclaiming Africa for the west, had won round two. Eutropius’s plot had failed, and this made him vulnerable. Soon, he went the same way as his dead predecessor Rufinus; the Goth general Gainas arrived at the court of Constantinople with his army, demanded that the emperor put Eutropius to death, and then took his place as the third puppet-master to control Arcadius. In less than a year, Gainas too lost his head, and another Goth soldier, named Fravitta, became Arcadius’s consul and advisor.

11.1: The Visigoth Invasion

Then yet another crisis struck Stilicho and Honorius in the west. In 400, the Visigoth king Alaric—still leading his new nation—invaded the north of Italy. The Visigoths came not just with their fighting men, but also with their women and children. They intended to settle. Alaric had a nation; now he was in search of a homeland.

The Visigoth invasion forced Honorius and his court to flee from Milan and take refuge in the city of Ravenna. Ravenna was ringed with swampland and relatively easy to defend, but it was an impossible place from which to launch a fight against the Visigoths. The western Roman empire was entrenching and shrinking. For two years, the Visigoths spread across the north of Italy.

Meanwhile, in the east, Arcadius had fathered a son: the future emperor Theodosius II. It had become the custom for emperors to appoint their infant sons as co-emperors; that way, if the father died, a crowned emperor was already in place to succeed. But Arcadius was afraid that declaring his son his co-emperor would sign the child’s death-warrant. Should Arcadius die—and Arcadius knew just how precarious his hold on life was—no one would protect his son’s power. “Many would inevitably exploit the boy’s isolation and make a bid for the Empire,” writes the Roman historian Procopius, “and once they had attained it, they would easily usurp the throne and kill Theodosius II, who had no relative to be his guardian. He did not imagine that the divine Honorius would help, for things were now bad in Italy.”

9

Instead, Arcadius turned to the Persians. Persia had been at peace with the east since Stilicho’s negotiations on behalf of Arcadius’s father, twenty years earlier; the Persian king who had agreed to Stilicho’s terms, Shapur III, had been succeeded by his younger son Yazdegerd I. Yazdegerd, says Procopius, “adopted and continued without interruption a policy of profound peace with the Romans.”

10

So marked was the friendship Yazdegerd offered that Arcadius, who trusted no one within his own empire, asked Yazdegerd to act as guardian to his baby son.

“T

HINGS WERE BAD

in Italy,” Procopius had written, but they were about to get better. In 402, Stilicho managed to halt the Visigoth invasion. He met Alaric and his army on April 6, at the Battle of Pollentia, and defeated them.

It was not an entirely honorable victory; April 6 fell on Easter weekend, and Alaric, barbarian though he may have been, was a Christian who assumed that Easter was a sacred holiday on which fighting was banned. Stilicho, ignoring the prohibition, drew up his troops and (according to the poet Claudian) exhorted them by shouting, “Win a victory now and restore Rome to her former glory; the frame of empire is tottering; let your shoulders support it!”

11

The fighting that followed was bloody and costly for both sides, but it ended when Stilicho’s soldiers stormed into Alaric’s camp and captured his wife. The two men negotiated a treaty that returned Alaric’s wife to her husband and gave northern Italy back to Stilicho. Alaric retreated back across the Alps, still without a homeland.

12

But despite the victory in Italy, the empire continued to totter. Roman Britannia was in serious trouble. When Magnus Maximus had crossed over into Gaul to claim the throne, he had taken the best part of the Roman army with him, and for years afterwards the remaining soldiers battled desperately against the “fierce peoples of Britain,” invaders from the northern lands and from the sea. In 407, the remnants of the Roman army in Britannia, exasperated with the court politics in distant Ravenna, proclaimed one of their own generals emperor, as Constantine III. Like Maximus, Constantine III wasn’t happy merely to be emperor in Britannia, which was still the Siberia of the Roman empire; he set out to conquer Gaul and Hispania as well.

13

While Constantine III was heading eastward, Honorius made a sudden bid for independence. He was now twenty-three and presumably tired of having his life and his empire run for him by Stilicho. He had begun to hear rumors that Stilicho was planning a match between his own son and Honorius’s sister Placida; raised by Stilicho and his wife after Theodosius’s death, Placida was now eighteen. This sounded like a play for power: Stilicho might be resigned to never holding the title of emperor himself, but his son, with less Vandal blood and with a royal wife, might well ascend to the imperial throne.

14

Honorius allowed himself to listen to the Roman officials at his court who accused Stilicho of planning treason; he arrested his former guardian, and on August 23 Stilicho, not yet fifty and with over thirty years of service to Rome behind him, was put to death at Ravenna.

With his formidable old opponent dead, Alaric the Visigoth immediately came back from his wanderings in central Europe and laid siege to the city of Rome. The Roman Senate tried to negotiate a peace, agreeing to pay him gold, silk, leather, and pepper if he would withdraw. Alaric took the ransom and withdrew, but he hadn’t been merely seeking wealth. In 409, he sent a message to Honorius, threatening a second siege of Rome if Honorius didn’t give him land in Illyricum for his Visigoths to settle on. Alaric was still in search of that elusive homeland.

*