The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (8 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Between 364 and 376, natural disaster and barbarian attacks trouble the Roman empire

J

OVIAN’S DEATH MEANT

that the Roman empire had three emperors in four years: a “ferocity of changeable circumstances,” Ammianus Marcellinus calls it, a time when Rome’s religion and Rome’s frontiers had shifted as quickly as Rome’s chief official.

No one supported the claim of Jovian’s infant son. Instead, the army (which had become, without design, representatives for the entire empire) chose another officer to be the next emperor.

Valentinian was forty-three, a lifelong soldier and a zealous Christian, something that makes it slightly difficult to get an accurate portrayal of him from the contemporary sources. The historian Zosimus, a devotee of traditional Roman religion, remarks grudgingly that Valentinian was “an excellent soldier but extremely illiterate” the Christian historian Theodoret rhapsodizes that Valentinian was “distinguished not only for his courage but also for prudence, temperance, justice, and great stature.”

1

What the empire needed at this point was not a learned leader but an experienced general, and Valentinian’s decisions suggest that his army service hadn’t necessarily qualified him to be emperor. He was at Nicaea when the army acclaimed him; before setting out for Constantinople to be crowned, he decided to declare a co-emperor. This was a soldier’s precaution. Life was cheap along the roads in the eastern provinces, and Valentinian had no heir.

According to Ammianus, he gathered his fellow officers together and asked what they thought of his younger brother and fellow soldier Valens. There was a silence at this, until finally the commander of cavalry said, “Your highness, if you love your kin you have a brother, but if you love the state look carefully for a man to invest with the purple.”

2

It was advice that Valentinian decided to ignore. He gave his brother the imperial title and put him in charge of the eastern empire as far as the province of Thracia; then he travelled to Italy, where he set up his court not in Rome, but in Milan.

This was a brief reorientation to the west, with the senior emperor taking up residence in Italy and the junior emperor in the east, although Valens settled not at Constantinople, but at Antioch, on the Orontes river. And it almost immediately became clear why the commander of cavalry had reservations. The empire had all sorts of military problems. Germanic tribes were invading Gaul and pushing across the Danube; the Roman holdings in Britannia were under attack by the natives; the North African territories were suffering from the hostility of the tribes to the south; and Shapur, claiming that the treaty he had sworn with Jovian was nullified by Jovian’s death, was getting ready to attack the east.

3

But Valens, in the east, was apparently more worried about inner purity than outer threat. His older brother Valentinian held to Nicene Christianity but was tolerant both of Arian Christians and of adherents to the traditional state religion. In fact, one of Valentinian’s most aggressive moves was to pass a law restricting evening sacrifices to the gods, but as soon as one of his pro-consuls pointed out that many of his subjects held to these ancient customs as a way to define themselves as part of Roman society, Valentinian immediately ordered everyone to disregard his brand new regulation.

4

But the younger Valens belonged to the Arian branch of Christianity, and he was entirely intolerant of any other form of doctrine. He began a war of extermination against the Nicene Christians in Antioch: exiling their leader, driving out the followers, and drowning some of them in the Orontes. This gave the Persians even more freedom to harass the eastern border, since the inexperienced and preoccupied Valens did little to garrison the fortresses on the east. Valens, Zosimus says, had so little experience with governing men that he could not “sustain the weight of business.” The soldier Ammianus puts it even more succinctly: “During this period,” he writes, “practically the whole Roman world heard the trumpet-call of war.”

5

And then catastrophe struck.

At dawn on July 21, 365, an earthquake rumbled from deep beneath the Mediterranean Sea, spreading along the seabed and rising up to the Roman shores. On the island of Crete, buildings collapsed flat on their sleeping occupants. Cyrenaica was shaken, its cities crumbling. The shock travelled up to Corinth, shivering its way across to Italy and Sicily on the west, Egypt and Syria to the east.

6

As Romans all around the coast began to pick their way through the rubble, putting out fires, digging out possessions, and mourning their dead, the water on the southern coast—right at Alexandria, on the Nile delta—was sucked suddenly away from the shore. The people of Alexandria, diverted, went out to the waterfront to see. “The sea with its rolling waves was driven back and withdrew from the land,” remembers Ammianus Marcellinus, “so that in the abyss of the deep thus revealed men saw many kinds of sea-creatures stuck fast in the slime; and vast mountains and deep valleys…. Many ships were stranded as if on dry land, and many men roamed about without fear in the little that remained of the waters, to gather fish and shells with their hands.”

The entertainment lasted a little less than an hour. “And then,” Ammianus writes, “the roaring sea, resenting, as it were, this forced retreat, rose in its turn; and over the boiling shoals it dashed mightily upon islands and broad stretches of the mainland and levelled innumerable buildings in the cities and wherever else they were found…. The great mass of waters, returning when it was least expected, killed many thousands of men by drowning.”

7

When the tsunami receded, ships lay in splinters all along the shore. Bodies had been tossed into streets and across the tops of buildings and floated face down in the shallows. Several years later, Ammianus, travelling to a nearby city, saw a ship that had been thrown two full miles inland; it still lay on the sand, its seams coming open with decay.

In the wake of the destruction, both Valens and Valentinian struggled to hold their domains together. Valens was challenged by the usurper Procopius, a cousin of the dead emperor Julian, who managed to convince the Gothic soldiers in the army to support his claim to the eastern crown. Valens sent a frantic message west to his brother Valentinian, asking for help; but Valentinian was far away on the battlefield, fighting the Alemanni (another Germanic tribal federation) in Gaul, and he did not have soldiers to spare.

8

With the help of substantial bribing, which turned Procopius’s two chief generals and part of his army against him, Valens managed to defeat Procopius in battle at the city of Thyatira. Once he had the rebel in his hands, he had Procopius torn apart. He also executed Procopius’s two chief generals, piously condemning them for their helpful treachery.

9

Traditional Roman chroniclers, like Ammianus, found in Procopius’s usurpation an explanation for the horrible wave; they simply moved the wave forward in time, placing it after the revolt and insisting that the rebellion had caused an upheaval in the natural order of things. Christian historians who write of the tsunami were more likely to blame it on Julian the Apostate; God was punishing the empire for Julian’s misdeeds. Libanius, Julian’s old friend, suggested that Earth was mourning Julian’s death; the quake and wave were “the honour paid him by Earth, or if you would have it so, by Poseidon.”

10

Christian or Roman, they all set out to make sense of the devastation. There had to be a reason for it. There was no place in either the Roman or the Christian world for an event that was not a direct response to human action—no place in either world for random evil.

T

HE NATURAL DISASTER

was followed, in short order, by a series of political catastrophes: barbarian attacks that pushed into Roman territory and chipped away at the edges of Roman power.

Valens initiated the first catastrophe by declaring war on the Goths. The Gothic soldiers in the army had supported the usurper Procopius, and he wanted to punish them.

Up until this point, the Romans and Goths had worked out a means of coexisting; the Goths provided soldiers for the Roman army, and in return were allowed to settle in Roman land with some of the privileges of Roman citizens. And they had become increasingly Christian over the past decades. Their native bishop Ulfilas had invented an alphabet and had used it to translate the Bible into their own language, and Ulfilas, like Valens himself, was a zealously Arian Christian. (Nicene Christianity, he preached, was an “odious and execrable, depraved and perverse…invention of the Devil.”)

11

None of this kept Valens from launching his punitive campaign against the Gothic-settled lands. His war of revenge began in 367 and dragged on for three full years without any particular resolution. It was a bad time to start a war against a people who were inclined to be friendly; in the west, Valentinian was already fighting the Alemanni. Late in 367, as Valens fought against the Goths, the Alemanni surged across the Rhine and attacked Valentinian on his own ground. Valentinian managed to defeat them in a pitched battle, but lost so many men that he was unable to push the invaders back out.

Meanwhile, the Roman holdings in Britain were also under barbarian attack.

In this case, the “barbarians” were the tribes who lived to the north. Back in

AD

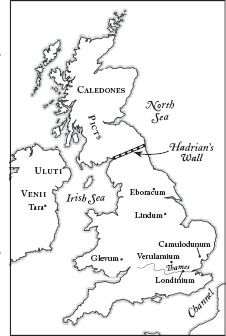

122, the Roman emperor Hadrian had drawn a line between civilization and wilderness by building a wall across the island. Roman Britain—the province of “Britannia”—was south of the wall. Six towns in Britannia had been given the status of full Roman citizenship.

*

The largest, Londinium, had twenty-five thousand inhabitants and a complex Roman infrastructure: shipping lines, baths and drainage, military installations.

12

To the north, as far as the Romans were concerned, lay only wilderness.

The tribes who lived north of Hadrian’s Wall, as well as on the smaller island west of Britannia, had arrived on British shores as invaders, perhaps in 500

BC

. Now

they

were the natives (a thousand years of habitation has a funny way of rooting a people into their land), masters of scores of tribal kingdoms. The strongest tribes were the Picts and Caledones (“red-haired and large-limbed,” wrote the Roman historian Tacitus). On the western island, which had never been invaded by Romans, the Venii dominated the south from their capital city of Tara, while the Uluti controlled much of the north.

13

Britannia had been troubled for more than a century by land invasions from northern Picts, as well as piratical raids launched by tribes on the western island.

*

In the fourth century, these were joined by sea attacks from another Germanic tribe: the Saxons, who came from the lands north of Gaul and sailed across the ocean to plunder the eastern coast of Britannia.

The Roman official who was in charge of defending Britannia from these attacks was the Dux Britanniarum. He was aided by a special commander called the Comes Litori (“protector of the shore”), whose job was to keep the Saxons away from the southeastern coast. But in late 367, while Valentinian was frantically beating back the Alemanni and Valens was deadlocked with the Goths, the British defenses in Britannia fell apart, and barbarians poured into the country from all four sides.

14

6.1: Britain and Ireland

It was a carefully planned and coordinated attack; Ammianus Marcellinus calls it the

Barbarica Conspirato

, the “Barbarian Conspiracy.” Roman garrisons stationed at Hadrian’s Wall, who had been fraternizing with the Picts for years, allowed Pictish soldiers to cross over into Roman Britain. At the same time, pirates from the western island landed on the coast, and Saxons invaded both southeast Britannia and northern Gaul. Both the Dux Britanniarum and the Comes Litori were overwhelmed; in the past decades, Roman forces in Britannia had been slowly depleted by transfers to the army over on the mainland.

15

Although he had his hands full of Alemanni, in 368 Valentinian sent the experienced general Theodosius the Elder over to Britain to try to retake the Roman provinces. Theodosius the Elder went, obediently, taking with him as vice commander his son Flavius Theodosius. He established himself at Londinium, from where he waged a year-long war that finally restored Roman control of Britannia. “He warmed the north with Pictish blood,” one Roman poet wrote, admiringly, “and icy Ireland wept for the heaps of dead.” New forts were built along the southeastern coast, with towers where guards could keep an eye out for the approach of Saxon ships.

16

But all was not well. The invasions had ravaged cities and burned settlements, wiped out entire garrisons, and destroyed the trade that had once existed between Britannia and the northern tribes. The Pictish villages near the Wall had now been burned, their people slaughtered, and along the border the Roman garrisons had shut themselves into crude and isolated fortresses.

17