The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (81 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

After seven years of fighting, Sancho the Strong managed to drive his brother Alfonso out of Leon. He reunited Castile and Leon into one kingdom, while Alfonso took refuge in the

taifa

kingdom centered around Toledo. But like his grandfather, Alfonso was crafty and willing to shed family blood; he paid off one of Sancho the Strong’s own soldiers to kill the king during the siege of an outlying city. “By treachery,” says the

Historia Silense

, “the king was transfixed with a spear by him, unexpectedly, from behind, and shed his life together with his blood.”

12

Alfonso denied until his death that he was involved in Sancho’s murder, but the benefit came to him; with his brother dead, Alfonso returned from his exile in the Muslim lands and reclaimed both kingdoms as Alfonso VI of Castile and Leon. He also inherited Sancho the Strong’s army, along with its general, El Cid.

Alfonso did his best to buy El Cid’s loyalty, giving him a position at court and a royal cousin as his wife. But he never fully trusted his dead brother’s general, and over the next few years El Cid was sent on numerous foreign trips, acting as Alfonso’s ambassador to the

taifa

kingdoms in the south and east. This kept him out of Castile and Leon and away from Alfonso, but it also gave him a chance to demonstrate his brilliance as a warrior. Some time around 1080, he was dispatched for a friendly visit to the

taifa

kingdom at Seville, which was under the rule of the Arab king al-Mu’tamid. While he was there, Seville was attacked by the neighboring

taifa

kingdom at Granada. El Cid and his men marched out with al-Mu’tamid to assist him in his fight against the army of Granada. El Cid fought so ferociously that he won all credit for the victory. He wrapped up this performance by attacking Toledo, taking seven thousand captives and wagons of treasure back to Castile and Leon with him.

“In return for this success and victory granted to him by God,” his biographer laments, “many men both acquaintances and strangers became jealous and accused him before the king of many false and untrue things.” Alfonso was jealous of El Cid’s reputation and popularity, and he took the attack on Toledo as an excuse to exile El Cid from his kingdom. The anonymous twelfth-century poem that praises El Cid’s heroic exploits adds that Alfonso also sent his men to sack El Cid’s home:

rifled coffers, burst gates, all open to the wind,

nor mantle left, nor robe of fur, stripped bare his castle hall.

13

Deprived of his home, his lands, and his profession, El Cid exercised his professional skill in the only way he could: he became a mercenary. His reputation ensured him of employment, and he was snapped up at once by the Arab king of Zaragoza, a

taifa

state with its capital not far from Alfonso’s border.

This put him on the wrong side of his previous employer. Although the two men did not come face to face in battle, El Cid was fighting for the Arabs, and Alfonso VI was planning a serious attempt to reconquer large parts of Muslim Spain. In 1079, he captured the city of Coria, well south of his own kingdom, and by 1085 he had pushed eastward all the way to Toledo, center of one of the stronger

taifa

states. When he conquered it, ripples of fear went through the surviving

taifa

kingdoms: if Alfonso VI managed to fight his way through the

taifa

kingdoms all the way to the coast, he could divide the northern and southern

taifa

kingdoms from each other and pick them off, one at a time. They could not fight the determined Christian advance without reinforcements.

14

Led by the king of Seville, the

taifa

rulers sent an appeal across the Strait of Gibraltar to the North African Muslims known as the Almoravids.

Until this point, the Almoravids had been confined to North Africa. Originally an unruly collection of North African tribes, they had been shaped into a nation by a North African chief named Yahya ibn Ibrahim, who had come to power some fifty years earlier. The tribes had been vaguely Muslim for two centuries, but since they were spread across the western desert with no central city or mosque for them to gather around, their practice of Islam had become more and more idiosyncratic. In 1035, ibn Ibrahim, at that time merely the chief of one of the tribes, had made his way to Mecca for the sacred pilgrimage, the

hajj

. There he discovered just how odd the western African version of Islam was.

15

A reformer by nature, ibn Ibrahim spent years studying the faith practiced by the Arabs in Islam’s homeland, and when he returned to west Africa he brought with him a missionary, an

imam

named ibn Yasin. Ibn Yasin spent the next twenty years among the tribes, teaching them his brand of Islam. It was a militant and ascetic interpretation that ordered the heterodox believers to straighten up, shun alcohol, devote their time to prayer and fasting, study the Qur’an—and then to spread these practices, by force if necessary. “God has reformed you and led you to his straight path,” he told them. “Warn your people. Make them fearful of God’s punishments…. If they repent, return to the truth, and abandon their ways, let them be. But if they refuse, continue in their error, and persist in their wrongheadedness, then we shall ask for God’s help against them and wage Holy War on them.”

16

By 1085, the Almoravids’ dedication to holy war had roused them to conquer most of the northwestern African coast. Led by ibn Ibrahim’s brother Abu-Bakr, they built a capital city and central mosque at Marrakesh; they proclaimed their loyalty to the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad and took for their own the existing Abbasid laws and customs. In bringing his message to northwest Africa, ibn Yasin had also brought with him a template for life as an empire, giving these nomads a fast track to nationhood.

When the panicked message arrived from Seville, Abu-Bakr sent his cousin, the general Yusuf ibn Tashfin, to answer it. Ibn Tashfin transported an Almoravid army across the strait and marched north to fight against Alfonso VI. On October 23, 1087, the combined armies of the

taifa

kingdoms and Almoravids defeated the soldiers of Leon and Castile in pitched battle at Sagrajas, southwest of Toledo. The slaughter covered the ground with the dead: “There was no place for a foot but a corpse or blood,” wrote one chronicler.

Alfonso survived but was forced to flee the battlefield in agony, badly wounded in the leg. The defeat frightened him so badly that he recalled El Cid from exile to fight the Almoravid threat; El Cid agreed to come home in exchange for two castles, a small territory of his own, and a written pardon from Alfonso, which stipulated that “all lands and castles which [El Cid] might acquire” by conquering

taifa

territory would belong solely to him.

17

El Cid helped Alfonso’s armies hold the border of Leon-Castile in place. Meanwhile, ibn Tashfin was soon frightening the Muslims of the south as much as he had terrified the Christians. The

taifa

rulers who had invited him in knew their history; they remembered the conquests of Tariq in 711, which had first brought Islam to Spain, and they were aware that asking a North African army for help was not unlike asking a fox to guard the henhouse. But they had been desperate. As a shaky defense against Tashfin’s ambitions, they had managed to get him to promise that he would return to Africa as soon as the Christians were defeated.

18

By 1091, the promise was ancient history. Abu-Bakr had died in 1087, leaving ibn Tashfin as ruler of the Almoravid lands. Tashfin had conquered Granada, Cordoba, and Seville; southern Spain had become merely a province of the Almoravid empire, which now stretched from Marrakesh across the water. But the extent of the empire made it difficult for Almoravid armies to advance much farther north. Alfonso’s kingdom remained intact in the north. The peninsula was divided between the two empires; the

taifa

kingdoms, falling one at a time, were a thing of the past.

But with the peninsula divided into Christian and Muslim segments, El Cid resisted belonging to either. Instead, in 1094 he laid siege to the city of Valencia, on the eastern coast, between the borders of the northern Christians and the southern Muslims. Once the city was in his hands, he claimed it as his own under the terms of Alfonso’s pardon and moved into it. Around Valencia, he conquered himself a kingdom.

El Cid was now in his fifties, and he had spent his entire life fighting for Muslim kings against other Muslims, for Muslim kings against Christians, for Christian kings against Muslims, for Christian kings against their own brothers. He was tired of war and fed up with changing sides. And for a brief time, his kingdom was home to both Christians and Muslims, a brief mingling of faiths in a polarized land.

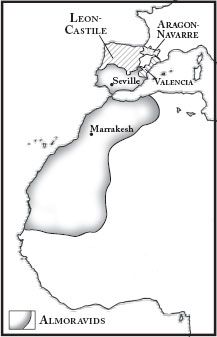

79.2: The Almoravid Empire

El Cid was no peacemaker; he killed the inhabitants of Valencia who opposed him, sacked villages that refused to surrender, and stole treasure from the conquered for his own personal use. But neither was he a zealot. He served neither Christianity nor Islam, but simply himself. Any Spaniard who behaved himself and obeyed El Cid could live in the kingdom of Valencia. In a world divided by religion, the great general’s self-interest had accidentally built an oasis of tolerance.

B

Y

1097,

THE

A

LMORAVID

commander Yusuf ibn Tashfin had conquered almost all of the land that had once belonged to the Caliphate of Cordoba; his Muslim empire stretched from northwestern Africa up into the south of Spain. The Christian realm of Leon-Castile, ruled by the long-lived Alfonso VI, dominated most of the north. The little kingdom of Aragon-Navarre was the junior power on the Iberian Peninsula; the only realm smaller than Aragon-Navarre was Valencia, the independent realm of El Cid, which lay on the eastern coast.

Valencia existed entirely through the strength and resolution of El Cid; when he died, Valencia fell. He drew his last breath peacefully in his bed in 1099, at age sixty. As soon as the news of his death reached the Almoravids, they marched against Valencia, invaded its territory, and besieged the city for seven months.

His wife finally sent an appeal to Alfonso of Castile, begging for deliverance. She knew that this would be the end of her independence as queen of Valencia, and so it was. Alfonso arrived with his army and fought his way into the city to rescue her, but he refused to commit himself to lifting the siege. “It was far removed from his kingdom,” the

Historia Roderici

tells us, “so he returned to Castile, taking with him Rodrigo’s wife with the body of her husband…. When they had all left Valencia the king ordered the whole city to be burnt.” The Almoravids, who had backed away, returned and claimed the burned city. They “resettled it and all its territories,” the

Historia

concludes, “and they have never lost it since that day.”

19

The fall of Valencia was the beginning of a series of changes in the Spanish landscape. In 1104, Alfonso VI’s first cousin (once removed) inherited the throne of Aragon-Navarre and began a double quest: to reconquer the Muslim south and to reverse the relationship between Leon-Castile and his own kingdom so that the larger realm paid homage to the smaller. Like his elder cousin, he was named Alfonso; while Alfonso VI of Castile eventually earned himself the nickname “Alfonso the Brave,” the thirty-year reign of Alfonso of Aragon-Navarre earned the younger cousin the nickname “Alfonso the Battler.”

The Battler’s rise to power was assisted by the deaths, in rapid succession, of Tashfin, Alfonso the Brave’s only son, and Alfonso himself.

Tashfin died in 1106 at nearly a hundred years old. Preoccupied with age and infirmity, he had allowed the armies of Leon-Castile to push deep into Muslim territory in the years before his death. He left the Almoravid empire to his son Ali ibn Yusuf, who recognized the need to drive back the Christian invaders. In 1108, an Almoravid army commanded by ibn Yusuf’s two younger brothers laid siege to the border city of Ucles. Alfonso the Brave of Castile sent his fifteen-year-old son Sancho at the head of ten thousand troops to lift the siege. He had given the boy two experienced generals to help him, and he expected a quick victory. But with the elderly Tashfin dead, the Almoravids had regrouped. In vicious fighting around the city, young Sancho and both of his generals were killed. The Almoravids occupied Ucles, creating a new frontier.

Alfonso the Brave, devastated by his son’s death and in failing health, had one surviving legitimate child: his daughter Urraca, who had been married and widowed several years before. Since she would inherit the crown of Castile and Leon, her father arranged for her to marry the king of Aragon; Alfonso the Battler, now an experienced soldier in his early thirties, could then defend the realm from the Almoravids.

20