The History of White People (8 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

Fig. 4.2. “Ossetian Girl,” 1883.

Next to weigh in was one of Kant’s younger East Prussian colleagues, the philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744–1803), who remains almost as influential. Although remembered for questioning the idea of an unchanging, universal human nature, Herder’s

Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit

(

Ideas for the Philosophy of History of Humanity

, 1784–91) carries on by connecting servitude, beauty, and the Black Sea / Caspian Sea region, “this centre of beautiful forms.” Like Kant’s treatise, Herder’s text—when translated into English—echoes Chardin, but changing Chardin’s Persians into Turks, and spelling with a lower-case

T

: “The

turks

, originally a hideous race, improved their appearance, and rendered themselves more agreeable, when handsomer nations became servants to them.”

14

In taking note of slavery’s alteration of a host society’s personal appearances, Chardin mentions a demographic role that upper-class Europeans and Americans seldom recognized at home.

Fig. 4.3. Georgians reading in the “Square of the Heroes of the Soviet Union in Tbilisi,” in Corliss Lamont,

The Peoples of the Soviet Union

(1946).

B

Y EARLY

in the nineteenth century, these iconic notions of beauty and its whereabouts had moved steadily westward, across France and over the English Channel into British literature. In

Travels in Various Countries of Europe, Asia and Africa

(1810), the prolific scholar-traveler Edward Daniel Clarke (1769–1822) considers the notion of Circassian beauty an established truth. The contrast between handsome Circassians and ugly Tartars appears prominently in Clarke’s narrative: “Beauty of features and of form, for which the

Circassians

have so long been celebrated, is certainly prevalent among them. Their noses are aquiline, their eye-brows arched and regular, their mouths small, their teeth remarkably white, and their ears not so large nor so prominent as those of

Tahtars

[

sic

]; although, from wearing the head shaven, they appear to disadvantage, according to our

European

notions of beauty.” And once again, Circassian beauty resides in the enslaved: “Their women are the most beautiful perhaps in the world; of enchanting perfection of features, and very delicate complexions. The females that we saw were all of them the accidental captives of war, who had been carried off together with their families; they were, however, remarkably handsome.”

15

Also in play were military rivalries that broke out around the Black Sea region, pitting the Russian and Ottoman empires against each other first during Greece’s war for independence in the 1820s and then during the Crimean War in the 1850s.

*

Both hostilities brought white slavery increased attention in the West, especially once word spread that Turkish slave dealers were flooding the market with Circassian women slaves before the Russians cut off the supply. Even Americans followed the Crimean War closely, picking up European culture’s enthrallment with the beautiful Circassian slave girl. This was only natural, given the American slave system, with its fascination for beautiful, light-skinned female slaves and growing sectional tensions, as exemplified in the figure of Eliza in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s best-selling

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

(1851–52).

16

*

The New York impresario P. T. Barnum, never one to ignore a commercial opportunity, took note of this purported glut of white slaves, and in 1864, as the Civil War raged, directed his European agent to find “a beautiful Circassian girl” or girls to exhibit in Barnum’s New York Museum on Broadway as “the purest example of the white race.” In the American context, a notion of racial purity had clearly gotten mixed up with physical beauty. Barnum cared a lot less about ethnicity than about how his girls looked, advising his agent that they must be “pretty and will pass for Circassian slaves.”

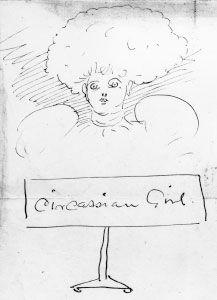

Barnum’s “Circassian slave girls” all had white skin and very frizzy hair, giving them the appearance of light-skinned Negroes. This combination reconciled conflicting American notions of beauty (that is, whiteness) and slavery (that is, Negro). In light of this figure’s departure from straight-haired European conceptions of Circassian slave girls, it was probably for the better that Barnum never imported the real thing. In truth, few in the United States knew what a Circassian beauty would actually look like. But by the late 1890s Barnum’s formulation had jelled sufficiently for Americans that the idly doodling artist Winslow Homer captured her essences of white skin and Negro hair. (See figure 4.4, Homer, “Circassian Girl.”)

17

Fig. 4.4. Winslow Homer, “Circassian Girl,” 1883–1910. Ink on paper drawing, 53/4 x 83/4 in.

The durable notion of Circassian beauty invaded even the classic eleventh edition (1910–11) of the

Encyclopædia Britannica,

which fulsomely praised Circassians as the loveliest of the lovely: “In the patriarchal simplicity of their manners, the mental qualities with which they were endowed, the beauty of form and regularity of feature by which they were distinguished, they surpassed most of the other tribes of the Caucasus.”

18

A

N INTRIGUING

disjunction dogs this literary metaphor—few images existed of actual people, whether in photographs, in paintings, or in the works of anthropologists. Such a deficit left nineteenth-century artists of the odalisque dependent on four sources: the eighteenth-century tradition of erotic art, all those sexually titillating scenes invented for aristocratic patrons; Napoleon’s time in Egypt from 1798 to 1801, which yielded a bounty of plundered objects and triggered a harvest of scholarly books; the early nineteenth-century French conquest of Algeria, which opened a window onto the Ottomans; and the Italian career of one of France’s greatest painters.

19

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), a wildly successful French painter when the French dominated Western fine art, began his career in Italy, a country rife with Eastern influences. His odalisques, epitomes of

luxe et volupté

, lounge languidly amid the splendor of the Turkish harem. They look like the girl next door, always so white-skinned that they could be taken for French. The result was a sort of soft pornography, a naked young woman fair game for fine art voyeurs. Witness

Grande Odalisque

(1814), an early Ingres work painted in Rome, which established his reputation. (See figure 4.5, Ingres,

Grande Odalisque

.) Typical of the Orientalist genre,

Grande Odalisque

depicts an indolent, sumptuously undressed, white-skinned young woman with western European features. Her long, long back to the viewer, she looks over an ivory shoulder with a come-hither glance.

Grande Odalisque

portrays the subject by herself, surrounded by heavy oriental drapery, but many other works feature a spacious harem full of beautiful young white women. Even when “odalisque” does not figure in the title, characteristic scenery and personnel designate the scene as the Ottoman harem and the naked white woman as a slave. Now and then black characters appear as eunuchs or sister slaves.

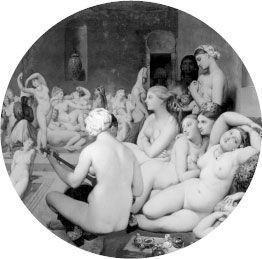

Le Bain Turc

(1863), painted when Ingres was eighty-three years old, displays a riot of voluptuous white nudes and one black one lounging about the bath and enjoying a languid musical pastime. (See figure 4.6, Ingres,

Le Bain Turc.

)

Fig. 4.5. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres,

Grande Odalisque,

1819. Oil on canvas, 91 x 162 cm.

American art was not far behind. The country’s most popular piece of nineteenth-century sculpture was

The Greek Slave

(1846) by Hiram Powers (1805–73). Larger than life and sculpted from white marble, it depicts a young white woman wearing only chains across her wrists and thigh. (See figure 4.7, Powers,

The Greek Slave

.) Granted, Powers’s title makes the young woman Greek not Georgian/Circassian/Caucasian, and a cross within the drapery makes her Christian rather than Muslim. But even so,

The Greek Slave

demonstrates Orientalist whiteness in its material, the white Italian marble so critical to notions of Greek beauty. When this monumental piece toured the United States in 1847–48, young men unused to viewing a naked female all but swooned before it. To be sure,

The Greek Slave

was no ordinary naked woman; Powers deemed his sculpture historical, the image of a Greek maiden captured by Turkish soldiers during the Greek war for independence. Only a few abolitionists drew connections between Powers’s white slave and the white-skinned slaves of the American South, where no measure of beauty or whiteness or youth sufficed to deliver a person of African ancestry from bondage.

20

Fig. 4.6. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Le Bain Turc, 1862. Oil on wood, 110 x 110 cm. diam. 108 cm.