Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

The History of White People (10 page)

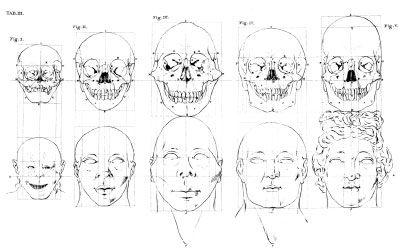

Camper’s most famous chart (likely drawn in the 1770s but not published until 1792, after his death) delivers sharply conflicting messages in a deeply confusing manner.

†

(See figure 5.3, Petrus Camper’s chart of contrasted faces.) Apparently comparing faces and skulls as viewed straight on with lines drawn through several points on each skull and face, the chart is intended to depict the “facial angles” of an orangutan (chimpanzee), at top left, a Negro, a Kalmuck, over to a European, and

Apollo Belvedere

, in that order. One source of confusion lies in the use of frontal views to illustrate measurements reckoned in the profile. The facial angles shown are 58 degrees for the orangutan/chimpanzee, whose mouth projects beyond his forehead; 70 degrees for both the Negro and the Kalmuck, whose faces are more vertical; 80 degrees for the European; and 100 degrees for the Greek god. Camper’s order introduces a further, crucial ambiguity.

As an advocate of human equality, Camper held all along that this chart demonstrates the near parity of the human races. The numbers associated with the chart—58, 70, 80, and 100—do, in fact, reveal Negro and Kalmuck facial angles closer to the European than to the orangutan/chimpanzee and less separate from the European than the European is from the Greek god. This, Camper maintained, was his message, whose fundamental meaning lay in his numbers. He insisted on the unity of mankind, even going so far as to suggest that Adam and Eve might well have been black, because no one skin color was superior to the others. Brotherhood, however, was not the meaning the chart conveyed to others.

Fig. 5.3. Petrus Camper’s chart of contrasted faces, 1770s.

A far different message emerges from Camper’s chart’s visual layout, one that completely undercut his egalitarian beliefs. Circulating at the height of the Atlantic slave trade in the late eighteenth century, his image places the Negro next to the orangutan/chimpanzee and the European next to the

Apollo Belvedere

. Position, not relative numbers, came across most clearly. The apparent pairing in this visual architecture soon embodied anthropological truth among laymen.

European scholars, meanwhile, were asking harder questions.

*

In France and Germany, Camper faced mounting criticism, and in the long run his paltry record of publication hindered his scholarly reputation. While he produced hundreds of papers and drawings, he published no one dominant book, and the “facial angle” lost credibility in academic science. By the mid-nineteenth century, methodical measurers of skulls had denounced Camper’s simplistic reliance on a single head measurement. But even as Camper lost scholarly standing in continental Europe, scientific racists in Britain and the United States such as Robert Knox, J. C. Nott, and G. R. Gliddon went on reproducing his images as irrefutable proof of a white supremacy that Camper himself had never embraced. Johann Kaspar Lavater of Switzerland traveled a somewhat parallel trajectory.

A

S A

P

ROTESTANT

clergyman and poet in Zurich, Lavater firmly believed that God had decreed one’s outer appearance, especially the face, to reflect one’s inner state. His illustrated books

Von der Physiognomik

(

On Physiognomy

, 1772) and

Physiognomische Fragmente, zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntis und Menschenliebe

(

Essays on Physiognomy Designed to Promote the Knowledge and Love of Mankind

, 1775–78) were immediately translated and widely circulated. Familiar among scholars and laymen alike, these works lavishly demonstrate the supposed correlation between personal beauty and human virtue, between outer looks and inner soul—an attractive and simpleminded notion.

Lavater amplified Winckelmann’s views on the ancient Greeks, dedicating sections of his masterwork,

On Physiognomy

, to “the Ideal Beauty of the Ancients.” He also repeated the commonplace that modern Greeks differed fundamentally from the ancients: “The Grecian race was then [in antiquity] more beautiful than we are; they were better than us—and the present generation [of Greeks] is vilely degraded!”

9

Although Lavater, like Camper, saw Greek beauty as typically European, he disagreed with Camper over the ideal facial angle, and this was an important feature in their minds. The forehead of Lavater’s Apollo sloped backwards rather than rising vertically. Of course, none of these (to us) trivial disagreements undermined the central concept of white beauty’s embodiment in the same Greek god.

Opinions swept back and forth across Europe on these racial matters. At first Lavater (like Camper) impressed practically everyone, including the young Goethe, with his vivid illustrations, and his books became best sellers. But Goethe and other supporters soon fell away as Lavater faced critics led by Blumenbach’s friend, the Göttingen intellectual Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742–99), known then for his witty epigrams (none understandable in English and now remembered mainly in Germany). Lichtenberg had excellent reasons for mistrust. According to Lavater’s theories, he—being humpbacked and uncommonly ugly in the popular view—would thereby lack inner worth: there was nothing Grecian about Lichtenberg. Camper, too, viewed Lavater’s work skeptically, even though the two men shared the same conceptual weaknesses.

Scholars also ultimately rejected Lavater’s views as too simplistic, yet his conceits—that the skull and face, in particular, reveal racial worth and that the head deserves careful measurement—lingered on among natural scientists.

10

Lavater, for his part, went much further, publishing books filled with portraits of the illustrious and the lowly in order to document what he deemed the close relationship between head shape and character. Both Camper and Lavater correlated outer appearance with inner worth through the instinct of “physiognomonical sensation,” and both used images of Greek gods to stand for the ideal white person; others they took from people off the street. Their theories and images, a huge extension of the association of whiteness with beauty, soon reverberated through the work of authors writing in English, as Camper’s and Lavater’s images moved across the English Channel through the learned lectures and publications of John Hunter and Charles White.

11

D

R

. J

OHN

H

UNTER

(1728–93), an overbearing, arrogant, unpolished Scot, had served as a surgeon in the British army during the Seven Years’/French and Indian War in North America. Returning to London in 1763, and now possessed of much practical knowledge, he gained high patronage positions (surgeon extraordinary to the king, surgeon general of the army, inspector of army hospitals) through advantageous political connections in prosperous Hanoverian London. By the mid-1780s Hunter also enjoyed the recognition conferred by membership in several learned societies.

*

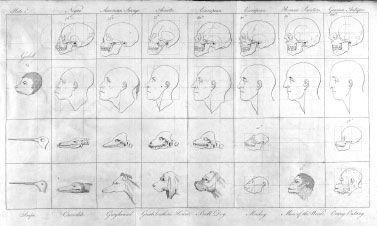

Scholarly communication between Europe and England flourished. Hunter knew Camper’s work and, like Camper, had analyzed a series of human and animal skulls to illustrate gradations of the vertical profile, an exercise rather similar to Camper’s work on the facial angle. Hunter compared various human skulls (

the

European,

the

Asian,

the

American,

the

African) to the skulls of an ape, a dog, and an alligator. And although he specifically denied any hierarchical intent, Hunter’s imagery inspired the obstetrician Charles White (1728–1813) to think about race as physical appearance.

Like Hunter, White had made his reputation as an innovative surgeon. Specializing in obstetrics, he was known as a “man midwife” and initially practiced alongside his physician father.

†

As eighteenth-century industrial Manchester grew in wealth and power, White’s social and intellectual reputation soared. Long interested in natural history, he increased his study of the links between various kinds of humans and animals in the 1790s. One of White’s illustrated 1795 lectures to the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (of which he was a founding member) appeared in print in 1799 as

An Account of the Regular Gradation in Man, and in Different Animals and Vegetables; and from the Former to the Latter

.

‡

(See figure 5.4, Charles White’s chart.)

Following Camper, White arranges his human heads (skulls and faces in profile) hierarchally, left to right, and names them by race, status, and geography. The “Negro,” whose mouth juts far out in front of the rest of his face, sits next to the ape. On the other side of the Negro are, in ascending order, the “American Savage,” the “Asiatic,” and three “Europeans,” one the model of a “Roman” painter. At the far right, next to the “Roman” painter’s model sits the “Grecian Antique,” whose nose and forehead hang far over his mouth. White’s text crucially departs from Camper’s, however, by questioning the descent of all people from a single Adam-and-Eve pair. Occasionally employing the word “specie” rather than “race,” White surmises that different colored humans grew from separate acts of divine creation. This view, soon known as polygenesis, traced humanity to more than the one origin of Genesis. Polygenesis went on to flourish in the mid-nineteenth century among racists of the American school of anthropology. While the publication of

The Origin of Species

in 1859 much reduced the allure of creationism of all kinds, Darwinism did not kill off polygenetic thinking entirely.

White correlated economic development with physical attractiveness, joining the lengthening lineage of those who considered the leisured white European not only the most advanced segment of humanity but also “the most beautiful of the human race.” To close his

Account of the Regular Gradation in Man

, White poses a series of rhetorical questions focused on two persistent themes of racial discourse: intelligence and beauty.

White asks, “Where shall we find, unless in the European, that nobly arched head, containing such a quantity of brain…?” The mention of brain leads to a physiognomy of intelligence that recalls Camper’s facial angle; White continues, “Where the perpendicular face, the prominent nose, and round projecting chin?” He ends with a soft-porn love note to white feminine beauty that incorporates the fondness for the blush found in many a hymn to whiteness. White and Thomas Jefferson shared with many others this enthusiasm for the virtuous pallor of privileged women.

*

White asks, “In what other quarter of the globe shall we find the blush that overspreads the soft features of the beautiful women of Europe, that emblem of modesty, of delicate feelings, and of sense? Where that nice expression of the amiable and softer passions in the countenance; and that general elegance of features and complexion? Where, except on the bosom of the European woman, two such plump and snowy white hemispheres, tipt with vermillion?”

12

Fig. 5.4. Charles White’s human chart, 1799, in Charles White,

An Account of the Regular Gradation in Man, and in Different Animals and Vegetables; and from the Former to the Latter

(1799).

I

N GUSHING

prose or in drier scientific utterance, beauty early rivaled measurement as a salient racial trait. While scholars seldom approached White’s exuberance of language, others of much greater influence got the science of race barreling along, with beauty steadily rising as a meaningful scientific category.