The History of White People (13 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

B

LUMENBACH’S IDEA

of Caucasian was as much mythical as geographical. On the one hand, he means the 170,000 square miles of land separating the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising the embattled Muslim Chechnya as well as Christian Georgia and being home to some fifty ethnic groups. Today anthropologists parse these ethnicities into three main categories: Caucasian, Indo-European, and Altaic. Among the Altaic peoples are the Kalmyk/Kalmuck, whom Western tradition deemed ugly. Right beside them live the Circassians and Georgians, those beautiful white slave people of legend, both in the category of Caucasian peoples. Note that in 1899 William Z. Ripley pictured Caucasians in his authoritative

Races of Europe

. (See figure 6.6, Ripley’s “Caucasus Mountains.”)

Fig. 6.6. “Caucasus Mountains,” in William Z. Ripley,

The Races of Europe

(1899).

W

HITENESS NOW

takes its place in racial classification, reorienting the science of human taxonomy from Linnaeus’s geographical regions to Blumenbach’s emphasis on skin color as beauty. Once Blumenbach had established Caucasian as a human variety, the term floated far from its geographical origin. Actual Caucasians—the people living in the Caucasus region, cheek by jowl with Turks and Semites of the eastern Mediterranean—lost their symbolic standing as ur-Europeans. Real Caucasians never reached the apex of the white racial hierarchy; indeed, many Russians call them

chernyi

(“black”) on account of their supposed wild troublesomeness.

18

Somehow specificity faded while the idea of a supremely beautiful “Caucasian” variety lived on, eventually becoming the scientific term of choice for white people. When scholars nowadays use “Caucasian” as racial terminology, they are harking back to the illustrious Blumenbach. But the term has a more complex genealogy, too, one connecting it to the larger history of race, beauty, and reactionary politics.

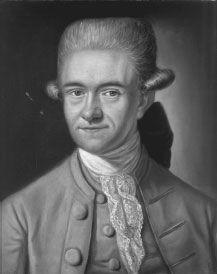

That part of the story brings in Blumenbach’s cranky Göttingen colleague Christoph Meiners (1747–1810). (See figure 6.7, Christoph Meiners.) For lack of documentation, we cannot know the exact degree of the personal interaction between Blumenbach and Meiners.

19

Clearly, however, Meiners, with his preoccupation with human beauty and his counterrevolutionary politics, shadows the background of German racial theory.

Both Blumenbach and Meiners studied and then taught at the University of Göttingen, where Meiners assumed a professorship in 1776, about the same time as Blumenbach.

*

The eminence of the egalitarian-minded Blumenbach lives on, and when Blumenbach died at eighty-eight, in 1840, his membership in seventy-eight learned societies attested to his eminence in the masculine realm of letters.

20

†

Led by the illustrious Humboldts, Blumenbach’s students had supervised the celebration of his jubilee—the fiftieth anniversary of his doctorate—in 1825. The politically retrograde Meiners has largely been forgotten.

During the 1790s Blumenbach, already the more distinguished colleague, seems to have taken note of Meiners’s voluminous, if obscure, publications.

21

To be sure, Meiners’s name appears only once in the 1795 edition of

Varieties of Humankind

, but Blumenbach’s emphases—notably beauty (and the evocation of an ancient Greek ideal), the repeated mention of Tacitus and the “ancient Germans’” racial purity, and even the name “Caucasian”—betray the pull of his contrary colleague.

Both Meiners and Blumenbach focused on the same towering subject—humankind’s divisions—but otherwise their views diverged over methodology, politics, and conclusions, converging only on the naming of varieties and, increasingly, the importance of personal appearance. Blumenbach, as we know, accorded pride of place to skull measurement, whereas Meiners relied on travel literature, with its inevitable ethnocentrism. Another difference: Meiners wrote hastily and at great length, distorting the meaning of scholars he cited and filling his pages with wildly contradictory claims. Blumenbach and more rigorous colleagues, though themselves no paragons of consistency, objected to such sloppiness, criticizing Meiners’s reactionary intellectual one-sidedness. Meiners made no bones about it—inferior peoples’ inferiority justified, even required, their enslavement and the use of despotism for their control.

22

Beauty and ugliness, he said, led naturally to different fates. Blumenbach did not agree.

Fig. 6.7. Christoph Meiners.

Meiners initially posited a counterintuitive binary racial scheme whose strange two-way racial classification appears in

Grundriß der Geschichte der Menschheit

(

Foundations of the History of Mankind

), published in 1785:

- Tartar-Caucasian, divided into Celtic and Slavic, and

- Mongolian.

The Tartar-Caucasian was first and foremost the beautiful race. The Mongolian was the ugly race, “weak in body and spirit, bad, and lacking in virtue,” as characterized by the Kalmucks. Meiners classifies Jews as Mongolian (i.e., Asian) along with Armenians, Arabs, and Persians, all of whom Blumenbach defined as Caucasian. Meiners makes his ugly Mongolian race dark-skinned. And he joined most of his German contemporaries in locating the ideal of human beauty in ancient Greece, but, he adds immodestly, the Germans rival the Greeks in beauty and bodily strength.

23

Göttingen’s scholarly community muttered a good deal about Meiners’s lack of rigor and cranky conclusions, but mostly the criticism remained buried in private and rather academic letters. In any case, Meiners’s fringy popularity was widespread, and his work circulated extensively.

Grundriß der Geschichte der Menschheit

went through three editions and was translated into several languages.

*

His circle included French counterrevolutionaries who later fed the intellectual history of twentieth-century National Socialism.

Blumenbach may well have borrowed the name “Caucasian” from Meiners. But even if that borrowing took place, Blumenbach reached for higher authority in publication. He cited the illustrious Jean Chardin, not his neighbor’s cantankerous book. Though Meiners lacked the status of a member of the Royal Society, he did convince a certain circle of his own acolytes.

In the early 1790s, Meiners began to move racial discourse in Göttingen beyond comparisons between Europeans and non-Europeans and to concentrate on an intra-European hierarchy of lightness and beauty, with ancient Germans on top.

24

In a series of articles vaunting the superiority of Germans among Europeans, Meiners describes non-German Europeans’ color as “dirty white” and compares it unfavorably with the “whitest, most blooming and most delicate skin” of the Germans. The early Germans he describes as “taller, slimmer, stronger, and with more beautiful bodies than all the remaining peoples of the earth.” Meiners maintains, following Tacitus, that Germans possess the prized quality of racial purity. By the late eighteenth century, Meiners was making claims for stereotypical Nordic/Teutonic attributes that some in the academic world would echo for another hundred years.

25

That was radical enough, but he did not stop there.

As his thought continued to evolve, Meiners teased out distinctions not only between different kinds of Europeans but also between different kinds of Germans: Germans of the north and Germans of the south. Northerners, such as the Protestants of Dresden, Weimar, Berlin, Hanover, and Göttingen were in; southerners—the Catholics of Vienna—were out.

This may seem a strained dichotomy, but, in fact, it was not new. At this time the idea of southern Germany meant Vienna, the sophisticated, nineteen-hundred-year-old capital of the Holy Roman Empire. That empire, self-proclaimed heir of the Roman empire of antiquity, sprawled across Europe from the Low Countries to the Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian lands bordering the Ottoman empire. It might have been on its next-to-last legs, but Vienna, created as a barrier against the Germani tribes, still occupied at least a rhetorical space between peoples within and those outside civilization. Thus differences between southern and northern Germans in the late eighteenth century could be thought to resemble Caesar’s and Tacitus’s civilized Gauls within the Roman empire and wild Germans—those northerners outside. Envy also played its part. A wealthy imperial capital, Vienna had long boasted a high culture beyond the means of Germans of the north.

Such envy coupled easily with contempt. It was only a small step for north Germans to feminize the Viennese, to turn them into soft Gauls and trumpet the enduring masculinity of untamed northerners. This anticivilization strategy gendered north and south, Gaul and German, a Gaul/French, German/German metaphor that held a promising future as an anthropological strategy. It also contained a political dimension. Like most advocates of racial hierarchy, Meiners resented the French for their revolution, which had led to unfortunate leveling tendencies in the German lands and, critically, to Jewish emancipation.

It is not surprising, therefore, that Meiners later became the Nazis’ favorite intellectual ancestor, for he knew his Tacitus and built castles upon it. In phrases characteristic of nineteenth-century Teutomania, Meiners describes Germans’ possession of the “whitest, most blooming and most delicate skin,” the “tallest and most beautiful” men not only in Europe, but in the entire world, and a “purity of blood” that made them the physical, moral, and intellectual superiors of everyone. The ancient Germans were “strong like oak-trees,” but their descendants, though still better than everyone else, had degenerated through indulgence in civilization’s luxuries. Rigorous practice of the martial arts would restore Germans to their former virility and beauty.

26

Some in Europe lapped up this super-racist theory, as Meiners attracted a coterie of French counterrevolutionaries in the late 1790s, including Jean-Joseph Virey, whose

Histoire naturelle du genre humain

(1800) divided humanity into “beautiful whites” and “ugly browns or blacks,” and Charles de Villers.

27

A correspondent with Madame Germaine de Staël and an expert on Kant, Villers settled in Göttingen and studied with Meiners. With his influence on de Staël, German racial theory moved west. It consisted of a bundle of notions predicated on contrasts between European and African, but also between European and Asian, northerner and southerner, lighter and darker, and Germans and French.

I

n the world of influence and the transmission of ideas, it is good to be rich, and Anne-Louise-Germaine Necker de Staël (1766–1817) was one the richest—materially and intellectually.

1

(See figure 7.1, Madame de Staël.) Without question a giant of her age, de Staël wrote novels featuring beautiful, smart, and independent protagonists who star as foremothers for women writers to come. Reaching across time and space, her work has inspired women writers as various as George Sand, George Eliot, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Willa Cather. De Staël also furnished a template for the American transcendentalist Margaret Fuller, the brainiest in her company of elevated spirits.

2

All of that was yet to come, but in her own time de Staël also built the crucial conveyor belt between German thinkers of all kinds and a vast audience of lay readers in France, Britain, and the United States who lacked direct access to writing in German. She publicized the genius of Goethe, the naturalist religion of transcendentalism, and the way of categorizing Europeans as members of several different races. Her book

De l’Allemagne

(

On Germany

, 1810–13), in particular, forms the vital link between German and non-German intellectuals.

Possessing “a European spirit in a French soul,” Germaine Necker displayed a passionate intellectual curiosity early on.

3

Her mother, Suzanne Curchod Necker (1737–94), nurtured Germaine’s intelligence, exposing her to the best minds (Denis Diderot, Jean D’Alembert, Claude Helvétius, and other luminaries frequenting Madame Necker’s salon) and encouraging her even as a child to write novels and poetry. Such nurturing came naturally to the phenomenally wealthy Necker family. Jacques Necker, a Protestant banker originally from Geneva, had made a fortune in the financial world and gone on to serve as controller general of finances for Louis XVI. When Germaine at age twenty married an aristocratic Swedish diplomat, her husband received a dowry of £80,000, the equivalent of more than US$1.5 million in the early twenty-first century.

4

*

Fig. 7.1 Germaine de Staël as Corinne, by Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, French painter of the aristocracy, ca. 1807. Oil on canvas, 140 x 118 cm.

Although her husband soon squandered the dowry, Madame de Staël still continued to enjoy ample wealth and a large retinue throughout her life. She lived in her own château, traveled in comfort, and met other aristocrats on an equal footing. (She and her fellow exiles ran short of money while in England in 1792 only because the revolutionary government froze her French accounts.) Towering German intellectuals served her pedagogic needs. She learned German from Wilhelm von Humboldt, the Berlin aristocrat responsible for Prussia’s educational system and the founding of the University of Berlin and brother of the noted traveling scholar Alexander von Humboldt.

*

She also employed August Wilhelm Schlegel, a poet and critic known as an originator of German romanticism, as her son’s tutor.

Because she was a woman, descriptions of de Staël always mention her appearance. More charitable observers balance their evaluation of her looks with an appreciation of her brilliance. One 1802 visitor noted, “The man who should murmur against her lack of beauty would fall at her feet dazzled by her intellect. She was born an intellectual conqueror.”

5

The English avatar of romanticism, Lord Byron, thought she towered over all other women, concluding, “She ought to have been a man.” Like most of the men she encountered, Byron found her “overwhelming—an avalanche.”

6

Her first American biographer, the American feminist abolitionist author Lydia Maria Child, began her 1832 study of de Staël as follows: “In a gallery of celebrated women, the first place unquestionably belongs to Anne Marie Louise Germaine Necker, Baroness de Staël Holstein.”

But brilliance could not outweigh the nearly universal impulse to make unattractiveness—she was a fairly ordinary-looking, slightly plump matron—Madame de Staël’s main characteristic. Maria Child chose to note only her “finely formed hands and arms,” which Child described as “of a most transparent whiteness.”

7

In linking transparency to whiteness, Child employs a trope of white beauty whose illogic has not diminished its longevity. Transparent skin—skin with a minimum of melanin—is not white. Instead, it reveals the subcutaneous body as a mottled pink, blue, and gray. This is the “blue” of blue bloods.

*

On the other hand, the appearance of whiteness, of light skin color, requires some melanin to mask the darker blood vessels and flesh underneath. Thus, the metaphor of “transparent whiteness” may signify an idea of perfect whiteness in language, but it has little to do with actual physical appearance.

D

E

S

TAËL

matured during an age of literal revolution. The French Revolution, starting in 1789, with its Enlightenment ideals of human equality and brotherhood, reinforced trends already underway. On one side, it undercut arguments supporting slavery and inequality, fostering emancipation even in places beyond the reach of French power. On another side, however, French revolutionary ideology annoyed conservative believers in natural human hierarchy. De Staël rather tended toward the liberal side, but her lofty social status also attracted trouble.

In fact, de Staël fell quickly on two wrong sides of turbulent French politics. The too radical and too bloody revolution trampled her preference for a constitutional monarchy, which she loudly proclaimed. Her opposition to tyranny, her defense of unlimited freedom of speech, and her outspokenness as a woman made her persona non grata first in Paris and then in all of France. At least she had places to go: fleeing Paris in 1792, she crossed over to England and then doubled back to her family’s château at Coppet, Switzerland. Her parents, originally from the Lake Geneva region, had purchased the Coppet château on the lake before the revolution.

Returning to Paris in 1794, after the Reign of Terror, she leaped into politics, promoting Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup in September 1799 (or 18 Fructidor, according to the French revolutionary calendar) and maneuvering her former lover, the agile aristocratic diplomat Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand into his post as minister of foreign affairs. But politics did not occupy de Staël totally. Her literary career took off commercially with two novels,

Delphine

(1802) and

Corinne

(1807). Both feature the aforementioned brilliant, free-spirited, autobiographical heroines who soar intellectually and emotionally but must eventually fall victim to their limitations as women.

Delphine

and

Corinne

were widely translated and widely read, but

Corinne

became so famous that the very name still symbolizes a smart, independent-minded woman. This was not a figure likely to please Napoleon, whose relationship with de Staël quickly soured.

In a conflict of the “Emperor of Matter vs. the Empress of Mind,” Napoleon disapproved of Madame de Staël for almost two decades, from their first meeting in 1797 until his ultimate downfall in 1815.

*

Toward the end of his life Napoleon reread her

Corinne

, reminding him what he thought of her: “I detest that woman.”

8

Ostensibly it was her outspoken opposition to his policies and her Anglophilia that motivated his persecution, but he also simply could not stand a woman who was so loud.

And de Staël did talk incessantly, about politics and anything else. A friend called her a “talking machine.” To the men who heeded her views, her femininity seemed less essential than her intelligence. Although three children survived her, she failed to embody one of Napoleon’s fundamental womanly ideals: fecund motherhood. In 1803 he forced her to put 150 miles between herself and Paris. So she went to Weimar, in the Saxon center of German romanticism starring the poets Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich von Schiller, and on to Berlin, where she associated with the brothers Schlegel and Johann Gottlieb Fichte, inventors of early German romanticism, with its nature-centered themes of transcendentalism.

De Staël had already written a study of European literature,

De la literature considérée dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales

(literally “On Literature Considered according to Its Relationship to Social Institutions,” usually translated simply as

On Literature

, 1800). This work examines the literatures of Italy, France, and Germany; because Germany was only just becoming visible as a source of interesting literature, German intellectuals appreciated notice from a representative of French letters, even an exile. Even a woman. The success of

On Literature

and the warmth of its reception in Germany inspired three German research trips, in 1803, 1804, and 1807, in preparation for de Staël’s greatest work of nonfiction,

De l’Allemagne

(

On Germany

).

During most of Napoleon’s reign de Staël remained exiled outside her beloved Paris, her book on Germany unpublished. Napoleon had seen to that, ordering the destruction not only of the entire 5,000-copy print run of

On Germany

but also of its plates and manuscript. Fortunately de Staël somehow managed to salvage the plates and manuscript for later publication. Such a severe blow to her writing raised fundamental questions: Should she admit defeat, give up on life in Europe, and start afresh in the New World? She and her seventeen-year-old son, Albert, secured passports and prepared to immigrate to the United States.

I

N

1810 de Staël wrote to President Thomas Jefferson, saying she and her son planned to make a life in the United States. The president and de Staël were not strangers. Decades earlier he had frequented her Paris salon. In a warm return letter Jefferson assured her that her military-aged son would find a good welcome in the United States. About Madame de Staël herself, however, he said nothing, a silence that spoke volumes about the current state of American society. Jefferson knew de Staël could never have survived a long stay in such a crude land. Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, one of de Staël’s closest friends, had spent much of 1795 in the United States as a young man, and the experience had driven him to a singular conclusion: “If I stay here another year I’ll die.”

9

Certainly, no American city of the early nineteenth century could give de Staël the brio she enjoyed in Paris. Furthermore, by 1810 not only was de Staël no longer young—at forty-four years old—but she was also addicted to opium, and fragile in health. She obviously needed her brilliant retinue as much as her European setting.

De Staël actually owned land in upper New York State on the shores of Lake Ontario, purchased in 1800. An important factor in this purchase had been one of New York’s founding fathers, Gouverneur Morris (1752–1816), whom de Staël’s family had met in the early 1790s when Morris represented the United States in France. Ever the booster, he urged the rich Neckers to invest in American land. After de Staël and her father did so, Morris advised them on the management of their holdings.

Boosterism notwithstanding, Morris joined the chorus advising de Staël to stay put. During his years in Paris, Morris had experienced the gulf between American and French levels of sophistication. In the Necker/de Staël salon at Coppet, the “Estates General of European Thought,” Morris felt like a provincial bumpkin: “I feel very stupid in this group,” and “I am not sufficiently brilliant for this consultation,” he wrote in a letter back home. Hardly a dull American, Morris at home belonged to the highest reaches of American society. He had attended King’s College (now Columbia University) and studied with New York’s most prominent lawyer. No mean wordsmith, Morris wrote the phrase “We the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union.” Among Americans, Morris could never be a bumpkin. But even upon its highest summit, American society lacked the brilliance of de Staël’s French milieu. Morris described her salon as “a kind of Temple of Apollo.” Utterly lacking counterparts in the United States, she would wilt and die, for Americans “are ignorant of the charms of good French society.”

10

Over to the east, Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s leading poet, drew parallel conclusions. He had seen how the cream of Russian society bored de Staël to death when she visited there as a refugee from Napoleon’s France in 1812. Moscow’s best and brightest had tried to entertain her, but Pushkin realized they were simply not good enough: “How empty our high society must have looked to such a woman!…not a thought, not a remarkable word during these three long hours: frozen faces, a stiff attitude. How she was bored!”

11

Over time, Americans and Russians would often find themselves equated as members of young and promising, but crude, societies.