The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (18 page)

It was also at this meeting that Nina made it clear that if we were going to make this movie, we were going to do it right. She was not going to go down in history as the executive who screwed up

Hitchhiker’s.

It

had

to be rooted in Douglas’s world-view but to work for Disney it had to reach out to a new audience too.

Through the summer of 2003, Hammer and Tongs worked on the design, story and budget. A crucial part of finally moving into production was finding an approach which could be made to work at a budget level with which Disney were going to be comfortable. This was a challenge Nick and Garth relished. For them invention and problem-solving are worn as a badge of honour. In the autumn Roger Birnbaum decided that the pieces were now lined up. “We had a script, a director, a vision and a budget. Now was the time to find out if Disney were ready to play.” Under the terms of the agreement concluded when Spyglass had picked up Karey’s fee, Roger and Gary were now in control of the project and Disney had first right of refusal to be their financial or distribution partner. Nick and Garth flew out to LA and made their pitch to Nina. It was still by no means certain that Disney would go for it and Jay remembers calling Nina from his car on the Pacific Coast Highway and sensing that there was still some way to go before she was convinced.

On 17 September Nina took the meeting and, as Jay had promised, was bowled over by the energy and vision that Nick and Garth had. The final step was a meeting with Nina’s immediate boss, Dick Cook, chairman of Walt Disney Studios. A kind and highly respected executive, Dick was the final person who needed convincing, and after an agonizing wait of several days Nick and Garth, the Spyglass team, Jay and Nina gathered in his office on Thursday 25 September 2003 at 4:00 P.M. LA time. Garth, who in a wonderful Hollywood phrase is “very good in the room,” launched into his pitch. Dick heard him out and quietly asked if he could have the movie ready for next summer. Garth heard this to mean was it “technically” feasible to have it ready for summer 2005 and simply said that that was possible. Dick and Nina had a few whispered words with each other. As everybody was leaving the meeting and Garth was gathering up the designs and story boards he had used during his pitch, Dick said to Garth that if there was anything he needed he should just be in touch. It took Nina following everybody out to the lift to point out that the movie had just been greenlit. Even for experienced Hollywood players such as Roger and Gary and Jay, a greenlit movie with no caveats on cast was unusual and as the doors closed on the lift the whole team literally screamed for joy. I received a call at about 1:00 A.M. my time in London from Nick, who simply said, “We’re making a movie.” Jay came on the phone and was almost in tears. For all those who had worked with Douglas all those years it was truly a bittersweet moment; he had longed to hear those words, longed to be in a meeting just like that where a senior Hollywood executive said, “Yes, let’s make the

Hitchhiker’s

movie.”

Having greenlit the movie, Disney made two very important decisions. The first was to bring the project back in-house. Nina Jacobson’s faith in Nick and Garth and her excitement about the material in their hands made her determined to bring it centre stage at Disney in preparation for a major “live action” summer release. The second was perhaps even more important; having made a very bold creative choice in letting a first-time director and producer loose on a big-budget movie, Nina now also allowed Garth and Nick to hire the core creative team with whom they had worked in their music video and commercial career. The director of photography, Igor Jadue-Lillo, the production designer, Joel Collins, the second unit director, Dominic Leung, and the costume designer, Sammy Sheldon, were all key members of the Hammer and Tongs family. Indeed it was precisely because Garth and Nick had gathered around them a group of highly creative people with whom they had worked for many years that Nina felt confident in allowing them to simply “get on with it.” Spyglass remained as the movie’s producers and in late autumn 2003 we went into “pre-production,” the period in which the film is cast, scheduled and budgeted and the shooting script is prepared.

The story of how the key cast was gathered together is best told in their own words in the interviews that follow, but one theme occurs again and again as they reflect on the experience of working with Garth and Nick—the enormous attention to detail that lies at the heart of their approach. From the outset Garth and Nick were determined that

Hitchhiker’s

should not be a totally “computer-generated” galaxy. Even the most cursory of looks at their body of work shows their love of puppetry, of props that work “in camera,” of real sets. Of course in a movie like

Hitchhiker’s

there were always going to be some spectacular computer graphics, but in the end the actors spent very little of their time acting opposite a tennis ball on a stick on a sound stage covered in blue or green cloth. Henson’s Creature Shop in Camden, London, was hired to create the Vogons and dozens of “real” creatures with whom the actors could interact. Over the sixteen-week shooting period at Elstree, Frogmore and Shepperton Studios, and on location in North Hertfordshire, Wales and central London, the production design team created a series of lovingly realized “real worlds” for the cast to inhabit.

Probably the “holy of holies” for fans and cast alike was the

Heart of Gold

set. On the famous George Lucas sound stage at Elstree was built a fully realized interior for the ship. It was truly a thing of beauty: gleaming white curves, a magnificent control panel with the Improbability Drive button in the middle, a kitchen and even a bar area for the serving of Pan Galactic Gargle Blasters. And fittingly, on 11 May 2004, the third anniversary of Douglas’s death, it was on the set of the

Heart of Gold

that the whole cast and crew gathered for a minute’s silence to say thank you to Douglas. Jay Roach, who had his own moment’s silence in LA later that day, reflects: “It all started with Douglas and for all of us it has been about serving what was amazing about the radio plays and the books. The spirit of Douglas united all of us and none of us ever wanted to do anything that did not take it down a path that we hope he would have loved and that his fans will love. It needed to morph itself into this new channel but it didn’t need to be essentially anything other than it always was, this amazing prism that you could look at the world through and be inspired and uplifted by, and all of us knew that it would not work without that essence, and when we found Garth and Nick I genuinely thought that they would do a better job at letting that essence breathe than I would have done.”

Roger Birnbaum too considers that “this has been one of those great adventures in my career. When it takes a long time to get a film off the ground, and then it works, it makes it so much more satisfying . . . everybody has been passionate about this project and has gone the extra mile. We’ve done it for Douglas’s spirit.”

Over the long period of making a film there are many moments that stick in your mind. One such moment for me was when we were filming just outside Tredegar, South Wales, in a disused quarry (keeping alive a long and honourable tradition of British science fiction and quarries), and all day we had been jumping in and out of vans as the rain came in squalls, horizontally down the quarry. The producer from Henson’s Creature Shop was wrapped head to toe in Arctic-exploration gear she had borrowed from a friend, whilst in a splendid display of ruggedness some of the film crew remained in their shorts and Timberlands, no matter how cold it got. The rare periods of sunshine necessary for filming had been all too brief. But now in the gentle evening light I could see a very small man, standing all by himself in the middle of the quarry floor, trying to hold a large white head in place against the wind. I could also see the director, with his inexhaustible energy and enthusiasm, testing out a gadget that three of the lead actors were going to have to use the next day. By pushing a little button a paddle flicked up in front of him with alarming speed and stopped just short of his nose. Meanwhile a man in pyjamas and dressing gown, clutching a towel, passed the time of day with the president of the Galaxy. In the distance a Ferrari-red spacecraft, which had gouged out a fifty-metre trench when it had crash-landed, caught the sun on its tail fin.

The date was 1 July 2004. We were filming the exterior shots for the planet Vogsphere and not for the first time I felt a surge of pride and excitement that after so many years we were actually making “the movie” of

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the

Galaxy.

It was something that Douglas had wanted so badly and as usual that pride was mixed straightaway with deep sadness that he was not there to share it with everybody.

Many dozens of times during the pre-production and filming of

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

I was asked things like, “Do you think Douglas would have approved of the design for the box for the Ravenous Bugblatter Beast of Traal?” or “Would he have enjoyed the use of a thirty-foot-high sculpt of his nose as the entrance to Humma Kavula’s temple?” My answer was pretty much the same each time: it’s hard to say on the specifics of the box or the nose (though I can hazard a guess that in both those cases the answer would have been yes), but what I do know is that he would have been delighted by the passion, attention to detail and sheer creative exuberance that everybody involved in the production has brought to making the movie. And there in that tableau in the quarry—with Warwick Davis’s stand-in, Gerald Staddon,

7

helping to line up Marvin the Paranoid Android’s next shot; Martin Freeman and Sam Rockwell, as Arthur Dent and Zaphod Beeblebrox respectively, making the most of some pretty trying conditions; Garth Jennings putting a prop through its paces; and the crew doggedly climbing in and out of cramped cars—was everything that I hope would have made Douglas proud.

Robbie Stamp

London, December 2004

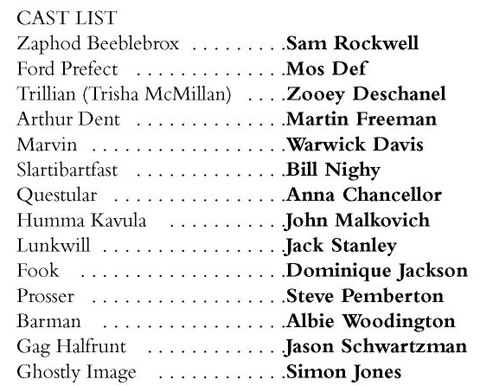

The Cast

For years, while the

Hitchhiker’s

movie was still in the pipeline, one of the favourite games for fans was to choose who they would cast in each role. Before he died Douglas Adams had this to say on the matter: “When it comes down to it, my principle is this—Arthur should be British. The rest of the cast should be decided purely on merit and not on nationality.”

The cast that was chosen fulfilled this wish and it was an exciting and unusual collection of actors who came to work on the

Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

movie in 2004. The full cast is as follows:

During filming, Robbie Stamp was able to talk extensively with the main human-cast members about how they brought to life Douglas Adams’s iconic characters. In a series of conversations in trailers, on golf buggies, in between takes and over the odd beer, the stars talked about how well they had known

Hitchhiker’s

before they were cast and what working on the movie meant to them. Those interviews follow.

Interview with Martin Freeman—Arthur Dent

Credits include

Shaun of the Dead, Love Actually, Ali G Indahouse

and “Tim” in

The Office.

Robbie Stamp:

Had you ever heard of

Hitchhiker’s

before you were approached about the movie?

Martin Freeman:

I certainly had heard of

Hitchhiker’s.

It was a bit of a favourite in my home growing up, not with me but with one of my brothers and my stepdad. I was very young when the series was on but I do remember watching that. I remember the books being in the house and kind of dipping and delving into those intermittently, but not reading the whole journey from start to end—but yes I was definitely, definitely aware of it, growing up.

RS:

And how did you get involved?

MF:

By being sent the script and reading the script, thinking I wasn’t right for it and then going to meet Garth and Nick and Dom.

8

I was more concerned with the fact that my girlfriend, Amanda, was on a double yellow line waiting for me. I thought, “I’m only going to be in there fifteen, twenty minutes.” But it was fifteen, twenty minutes before I even saw Garth because I’d been speaking to Nick and then Garth came and was very “Garthy” and really welcoming so we just chatted for another twenty, twenty-five minutes, then I went to do the reading. All the time I was thinking, “Christ, Amanda’s going to kill me,” so by the time we got in and read it I thought, “I’ve got to get out of here, I’m not even right for this! I’m not going to get it.”

RS:

Why did you think you weren’t right?

MF:

Because of my memories of the television series. I’m a very different actor to Simon Jones

9

and I think Simon Jones was Arthur Dent in my mind. And in a lot of people’s minds too— or if not Simon Jones then someone very like him, and that’s just not me. Anyway it transpired that they were very interested but had to see other people and had to work things out because I’m not a name and I always thought, “Why would anyone in Hollywood agree to me being the main part in a film?” Well, the main human, anyway. But after a bit of iffing and umming and other people passing and other people coming into the frame I was screen-tested again with Zooey

10

and that was that.

RS:

Your gut instinct that you weren’t right was the complete opposite of mine. From the moment I saw that first read I was convinced. While finding the essence of

Hitchhiker’s

we’ve all also been keen not to try and re-create what it was like twenty-five years ago.

MF:

Part of me would have thought you would go for a recreation of that, and if you didn’t go for that, that the approach would be ultra hip and trendy and cool, that you’d go for the exact opposite of past versions and get a nineteen-year-old kid to play Arthur Dent, and make it just really street or really urban, and I thought, “Well, I’m neither of those things.” That was why I thought at that original read, “I’ve got to get out. Amanda’s parked.” I think Garth picked up on that. We were very nice to each other and very friendly but I think he must have thought, “This guy just doesn’t care, and he’s not interested.” He was aware I was going to get told off, and I was told off! But it all worked out well.

RS:

Told off by . . . ?

MF:

By Amanda, she did indeed remind me that I had said I was only going to be fifteen minutes but I’m really glad that people took a punt on me and I’m very appreciative of it, because I know there are loads of people who in terms of film sense should’ve been in the queue before me.

RS:

So how did you start? When you’re thinking, “Well, I’m not a Simon Jones but I have been asked to play Arthur Dent, and he means a lot to many people,” what starts going through your mind?

MF:

Just what I had done in the audition. I thought if they liked that enough to be very interested then that’s what I’m going to do. Just trying to infuse it with reality and not playing Arthur Dent as we think we know him. It requires a bit of playing up because it’s a light kind of comedy, but I didn’t want it to not matter and I didn’t want it to not mean anything. I had to approach him as if I’d never heard of

Hitchhiker’s.

Because it would be very boring for me and everybody else to try and just do an impression of something that was à la mode twenty-five years ago. If Arthur had been very upper-middle-class with an Uncle Bulgaria dressing gown, if everything had basically been Edwardian, then the contrast with people like Sam and Mos

11

and Zooey, who are all very contemporary current people and although they’re not playing Americans are playing space people with American accents, just would’ve been another one in the long line of movies where the Americans are hip and the Englishman is a bit dull. It’s just not very interesting anymore. Take the dressing gown. There were certain points that they had to hit, in terms of my costume especially, that had to be in the film. I wasn’t going to say, “Can I wear a tracksuit or a suit?” It was always going to be a dressing gown, slippers and pyjamas. It was just a question of what kind and to be honest I wasn’t going to have too many objections. Sammy

12

is a good designer; she knows what she wants, and Garth has got his finger in every single pie, how it looks, how it sounds, everything. He’s got fantastic people working for and with him. My job is to come in and act. If I’d been presented with something I hated I would’ve said no, but as long as Arthur looked contemporary and it didn’t look like a joke, like we were judging him before he even opened his mouth, that was OK by me. From a make-up and hair point of view I just didn’t want him to look like a real mummy’s boy because that’s another thing about lame English men, they’re boring. They’ve got plastered-down hair and look like they’ve been dressed by their spinster mothers, but as long as he looked like a normal person who lived in the normal world that was all I needed to know because then I could play him as a normal person. I just didn’t want to play a caricature.

RS:

Very early on in the story we see Arthur lying down in front of a bulldozer: this is a guy who’s got something to him.

MF:

He has, he has, and I think it would take an enormous amount of balls for him to lie there . . . because that doesn’t come easy to him. It doesn’t come easy to most people to lie down in front of a bulldozer, but he gets on with it. It’s funny because to be honest my own jury is still out on whether I’ve got Arthur. I’ll see when the film comes out, because you never really know when you’re doing something, but Christ the world is full of films with people whose instincts are telling them it’s great and it ends up being terrible. I don’t think the film will be anything like that. I think the film will be really good and I’ll be a really feasible Arthur Dent, but we’ll wait and see.

RS:

Did the responsibility weigh on you?

MF:

To be honest I’ve let other people worry about that because I was never a Hitchhiking anorak. I hope I was respectfully aware that it was a big deal for lots and lots of other people, but they’re not playing it, I am. You can’t take on that responsibility for them and again, because I’m not a rabid

Hitchhiker’s

fan, it wouldn’t be like playing John Lennon, someone who means more to me in my everyday life. Or playing Jesus Christ or just someone who really, really

everybody

knows, and you really know the story and you’d better get it right. This is just an interpretation of a screenplay based on a book and a radio series and I’ve got as much warrant to play it as anybody else. We’ll see if I do it well. I’m just trying my best.

RS:

What about the relationship with Trillian? We have worked hard to develop her character.

MF:

Absolutely, and I think it’s to really good effect. It doesn’t look like it’s tacked on in a Hollywood way. It still has the essence of the original material. And I think without it, it wouldn’t be as good, to be honest.

RS:

So the first meeting with Trillian, at the party at the Islington flat; what’s happening, why is there a connection made?

MF:

Arthur’s a fairly intelligent bloke and I think a connection is made because Arthur sees someone . . . well, he sees a woman who is not afraid to come dressed as an old man and who is still physically beautiful. Not only has she come as a scientist, she gets jokes and references, more so than he thinks anyone else would at that party. It’s not as if he’s exactly outgoing. He’s in no position to say these people are idiots. What does he know? He doesn’t speak to anybody. He’s a typical repressed person, who is able to judge everyone from the comfort of knowing that he’s not actually going to find out if he’s right because he’s too shy. But here’s a woman who’s showed an interest in him and what a woman she is, she’s come as fucking Darwin. She’s gorgeous and she’s funny, who wouldn’t want that?

RS:

He was there reading a book by himself.

MF:

Absolutely, absolutely and she crossed the room to be with him. He was looking at her but she crossed the room. So all this looks very good until this strange person comes along and nicks her. And once he meets up with her again on the

Heart of Gold,

he goes from being just sad that she’s disappeared to being really jealous that she went off with Zaphod. Not only did she go off with someone else but it’s someone else who’s the total opposite of Arthur, not only not human but just an idiot in Arthur’s eyes, all the things Arthur wouldn’t want to be and all the things that he kind of would want to be. He wouldn’t want to be a moron but he would want to be a bit cooler and he would want to be more confident with women, but he’s intelligent enough to know that he can consider Zaphod beneath him because he treats women like objects, which Arthur would never do. But he blows it with her because of everything—the world is against him, he’s literally lost his planet, he’s lost his girl to an absolute idiot and she’s not giving him any proper attention. I think it’s even worse when you’re in a situation where the object of your desire is being nice to you and liking you, but that’s not enough, they’ve got to hate you or love you; anything in between is really upsetting and Arthur finds that very, very difficult. And he knows he’s overstepped the mark and he goes through different things with Trillian, being dumbfounded by her and apologetic to her, but by the end they have reached an understanding. He’s seen the best in her and she has really seen the best in him because he’s finally become a bit of a hero.

RS:

One of the finest lines to tread in developing this whole thing into a movie was to develop Arthur without turning him in to a mega-sword-wielding space hero.

MF:

Exactly. I think you only need to see him do a bit and the bit is that he sort of becomes the leader of the group. He doesn’t become an action man by Hollywood standards, but by Arthur Dent’s standards he becomes more of an action man. You see him come into his own. As the film goes on he becomes more his own person and has more authority and more conviction about what he’s doing. I guess there’s a point where he realizes, “I don’t have a home anymore so whatever this is I’ve got now I better start living in it, not trying to get home wishing something hadn’t happened that did happen.” He’s actually starting to take a bit of control and maybe in a way he could only take control in space. He couldn’t have taken control in his Earth job. Talking it all through it is a surprising movie. There aren’t many movies like this about finding the personal and the ridiculous in the universal. It’s not a big epic space adventure. It’s full of really ridiculous aliens and stupid fucking creatures—well, not [John] Malkovich. Humma Kavula is genuinely scary but there aren’t many like that. The Vogons are ridiculous. You can see they’re preposterous and they kill people with poetry, for fuck’s sake!

RS:

And there’s bureaucracy in space and a lot of the things that we’ve got on Earth, just a bit larger.

MF:

Exactly, and with funny heads. It’s a very human alien movie.

RS:

Talking of human aliens, what about your relationship with Ford?

MF:

Ford is my guide, my

Hitchhiker’s

guide. I’m not a hitchhiker, I’m a hostage. Arthur would be nowhere without Ford. He’d still be on Earth. In fact he’d be dead but due to a debt that Ford feels he owes Arthur, he takes Arthur with him and tells Arthur everything about survival in space, about who the strange creatures are and about what happens on this planet and what happens on that spaceship. So Ford really looks after Arthur.

RS:

And he’s genuinely affectionate towards him, isn’t he?

MF:

He is, as affectionate as Ford can be. It’s still not very recognizable as human affection; it’s slightly odd, and that’s kind of cool because Arthur’s slightly odd and not a particularly gregarious lovey-dovey person. So in that way they’re quite well matched. To begin with, Arthur thinks Ford is just a strange human and when he finds out that he’s actually from somewhere else entirely I suppose it makes a bit more sense to him why Ford’s like he is, but Ford is also totally viable as just an eccentric human being. Arthur certainly hasn’t twigged that Ford’s an alien before he tells him.

RS:

Have there been particular moments that stand out for you?

MF:

Yes. The

Heart of Gold

set—it was huge and we all walked round and went, “Fucking hell, we’re in a space movie.” To be honest, without fail, all of the settings have been amazing. It was the attention to detail, that’s what’s really, really impressed me, the design detail and the prop details have blown my mind. To be honest there aren’t particular scenes I’ve enjoyed more; it’s more the settings because I like

all

the scenes and some of them are fascinating to play from an acting point of view but it’s not like you’re doing Chekhov, it’s not like, “Fuck me, I’ve got a heavy dialogue day today and I’ve got to talk about how I lost my mother.” On the other hand, there are things to deal with, like how you lost the Earth. Those are the bits I found really hard, where Arthur has to be broken that the Earth has gone. They’re hard to play because it’s about pitching it at the right level . . . you’re not doing a kitchen-sink drama but you also want to make it real, you want to make it real enough that it matters. It’s not a tragedy, it is a comedy but you’ve still got to invest emotion in it. I think you always have to care about the people in films or the fish in films or the Shrek in films, you know? If you don’t really believe Arthur gives a damn then why would you give a damn?