The Hornet's Sting (2 page)

Read The Hornet's Sting Online

Authors: Mark Ryan

Tags: #World War; 1939-1945 - Secret Service - Denmark, #Sneum; Thomas, #World War II, #Political Freedom & Security, #True Crime, #World War; 1939-1945, #Underground Movements, #General, #Denmark - History - German Occupation; 1940-1945, #Spies - Denmark, #Secret Service, #World War; 1939-1945 - Underground Movements - Denkamrk, #Political Science, #Denmark, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #Spies, #Intelligence, #Biography, #History

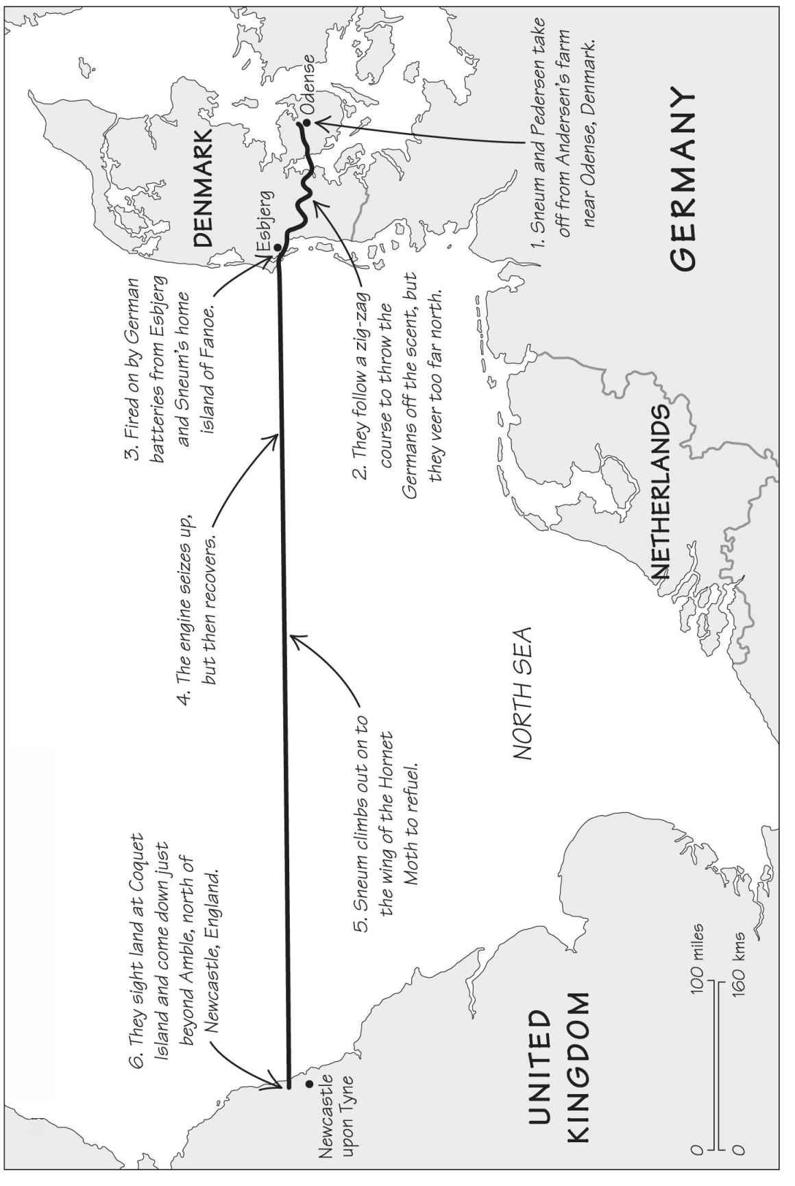

The epic Flight of the Hornest Month

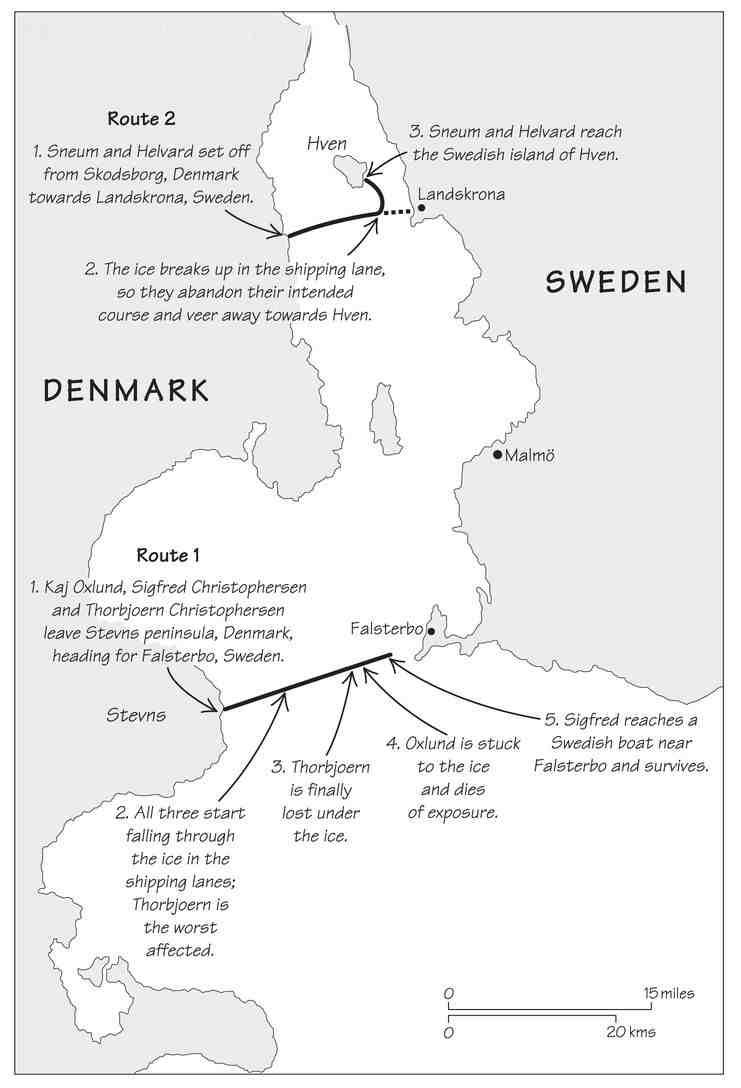

The Ice-Walks from Denmark to Sweden

W

HEN A FORMER MI6 SPY is pointing a Browning 9mm pistol straight at your chest, there isn’t much time to think about why you wanted to meet him in the first place. You are consumed by more immediate concerns, such as whether his wild-eyed stare means that he might just be crazy enough to pull the trigger. You search frantically for the right words to persuade him to calm down and point the pistol somewhere else. But all the time there is the fear that the wrong words might push him over the edge.

This living nightmare’s origins lay in Denmark, where a British national newspaper had sent me on an assignment. Some money had gone missing during the transfer of a Danish footballer to an English club. While investigating, I was driven along a busy Copenhagen highway which ran parallel with the Oeresund, the treacherous sea channel between Denmark and Sweden.

‘Did you know,’ said the taxi driver, ‘that some people tried to walk across that stretch of water to escape the Nazi occupation during the Second World War?’ He must have noticed the disbelieving expression on his passenger’s face. ‘It was frozen over at the time,’ the driver added, ‘but the ice wasn’t very solid. Some people made it; others didn’t.’

His story started me thinking: who were these people, so desperate to get away from the Nazis that they braved the fragile ice to try to reach a neutral country? I picked up history books and attempted some research. The years passed. Then I discovered that one of the men to whom the Copenhagen taxi driver had alluded was still alive. His was a particularly intriguing case, because he had spied for Britain during the war and remained a controversial figure, even as the twentieth century drew to a close. He was now said to be living in Switzerland. His name was Thomas Sneum. This sounded like a man worth meeting, even if it meant tracking him down in my spare time.

In February 1998 I flew to Switzerland in the hope of hearing Sneum’s story first hand. I called him as soon as the plane landed, the phone conversation was cordial, and he agreed to meet me the following day ... or so I thought. Waiting on his doorstep in peaceful, suburban Zurich on a cold, clear morning, I had no inkling of the reception he had prepared. Suddenly the door flew open and there he was, brandishing the pistol menacingly. Did Sneum think his visitor was merely pretending to be a reporter and was really someone far more threatening, recruited to exact revenge for some past misdemeanour? Maybe he held such a dim view of journalists that he felt this was the best way to greet them.

It was hard to see the funny side as this short, shrivelled man continued to aim his Browning directly at my heart. I kept my hands where he could see them and pleaded my case, trying to point out that there must have been a dreadful misunderstanding. Later he told me: ‘I can read people within the first few seconds of meeting them.’ In my case it wouldn’t have been difficult: the ltteof panic probably confirmed that I didn’t constitute any major threat. Gradually his anger seemed to give way to a more controlled suspicion. He refused to put the gun away, but he did eventually invite me in.

For such a notorious ladies’ man even to consider spending time in the company of someone who wasn’t a woman represented quite exceptional behavior, I would later discover. The fact that Tommy adored women—and they adored him—emerged quickly as one of the more obvious aspects of his story. As we became friends over the years, other vital components took much longer to establish.

Sneum’s pistol was just the first of many barriers to the truth over the next decade: for example, MI5 were still being obstructive in 2007. But from early on I was determined to get to the bottom of the story, which contained hidden depths almost as challenging as the Oeresund itself. It is fair to say that James Bond films have been made with more likely storylines. But Tommy Sneum’s story really happened. Ian Fleming’s hero wasn’t based on Sneum, but it is no exaggeration to say that he could have been.

‘James Bond was just a film character, and I would never have gone around shooting people under ridiculous conditions like he did,’ Sneum once pointed out. ‘Anyway, there were times during the war when James Bond would have gone back. I carried on.’

Tommy’s humour, his women and above all his spectacular stunts meant that he passed into wartime legend as either a lovable maverick or a deadly loose cannon, depending on your point of view.

‘People talk so much of what they will do,’ he told me. ‘I prefer to do it.’

The author Ken Follett readily admits that his novel

Hornet Flight

was inspired by just one extraordinary episode in Sneum’s eventful war. However, Follett’s understandable distortions in the name of fiction mean that the true story has, until now, never been told. Similarly, no film has ever been made to celebrate Tommy’s sheer audacity, or to examine his ruthless willingness to fight dirty when cornered.

In a letter dated 11 July 2006, MI5 did at least confirm two facts about Thomas Sneum: he had been investigated by the organization during the Second World War for possible treachery; and he had ultimately been cleared. But if they were prepared to admit that much, why wouldn’t MI5 release more information from their files about this agent?

Perhaps the answer lies in the shabby way Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) treated Sneum during the war. That he was investigated at all probably says more about the political infighting between the established SIS and its upstart rival, the wartime Special Operations Executive (SOE), than it does about Sneum’s capacity to double-cross those who stood in his way. At the same time, Tommy’s conduct wasn’t always exemplary either, largely because he considered himself too important, as a source of intelligence, to be compromised. That selfish streak was understandable, perhaps even excusable, in a brave man who risked his life for the Allied cause time and again. But the reader can be the judge of Tommy’s contribution to that cause, and the controversial conduct that often accompanied it.

R.V. Jones was so convinced of Sneum’s value to the Allies that he partly dedicated his book,

Most Secret War

, to the dashing young pilot. During the war, in addition to being a key scientific adviser to Winston Churchill, Jones was the assistant director of British Scientific Intelligence, one of the component sections of SIS. So he was better placed than most to determine whether Sneum’s name belonged in a list of celebrated super-spies. The dedication read:

To all those in Nazi-occupied Europe who in lone obscurity and of their own will risked torture and death for scientific intelligence, like ‘Amniarix’ (Jeannie Rousseau, Vicomtesse de Clarens), Leif Tronstad, Thomas Sneum, Hasager Christiansen, A.A. Michels, Jean Closquet, Henry Roth, Yves Rocard, Jerzy Chemielewski, and the author of the Oslo Report: To reconnaissance pilots like Eric Ackermann and Harold Jordan: and to the men of the Bruneval Raid.

‘For courage is the quality that guarantees all others.’

Sneum had a paperback edition of the book in his Zurich apartment. It contained a more personal, handwritten dedication from the author: ‘To Thomas Sneum, one of the heroes of this book and the war.’

However, Foreign Office documents recently revealed a very different view of Sneum’s wartime activities in the field, particularly when he was working with a wireless operator called Sigfred Christophersen. When the following extract was written, Major Geoffrey Wethered, who hunted double-agents on behalf of MI5 during the war, had just met with Commander Hollingworth of SOE’s Danish Section. Wethered reported: ‘During their adventures they [Sneum and Christophersen] appear to have given a great deal of information to the Germans about our activities in Denmark, to such an extent SOE sent a message to ARTHUR [the codename of leading SOE agent Mogens Hammer] ... informing him that Sneum had spilt the beans. None of this was told to us until today.’

Was Hollingworth’s accusation motivated by genuine concern about the loyalty of Sneum, an SIS agent, or by his own desire for political gain at a time when his position as an SOE spymaster was under threat? To what extent was Sneum simply caught in the crossfire of London’s interdepartmental rivalry between SIS and SOE? There was no love lost between the two British covert organizations, who rarely told each other what they were doing in the field, and often seemed at least as anxious to outwit their domestic rival as they were to undermine Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich.

After years of investigation into Sneum’s action-packed story, the true course of events can finally be told here. Was Sneum a hero or a traitor; a scapegoat or a villain? When it comes to the dark world of spooks, where does perception end and reality begin?

T

HOMAS SNEUM DIDN’T have time to think of a subtle way out of his first big crisis as a spy. It was unfortunate because no one on the British side knew about the extraordinary risks he was taking. The spy world in London was not even aware of his existence, and British Scientific Intelligence had no knowledge of the new Nazi installation which had drawn Sneum into such immediate danger. Mysterious towers had suddenly been erected where pine trees met sand dunes on his native island of Fanoe. And their strategic position, just off the west coast of Denmark, suggested that Adolf Hitler was preparing an unpleasant welcome for any British planes eyeing a route to mainland Europe across the North Sea.

The installation was visible in the distance, almost taunting Sneum; but his attempt to uncover its secrets, as he pretended to hunt rabbits on the surrounding heathland, had just been foiled by a rogue Alsatian’s ability to pick up his scent on the sea breeze. ‘That bloody dog came out of nowhere,’ he explained many years later, as if still struggling to make sense of what had happened.

Tommy knew he was in deep trouble. He could reason with people; he could play mind games and win. That was why he had struck up what he thought would become a useful rapport with the Germans who had occupied his country for the last few months. He even liked some of them. As a youngster, Sneum had played with German children on the tourist beaches of Fanoe just as often as he had played with their British counterparts. The rugged holiday island, just three kilometers wide and sixteen kilometers long, had been a paradise. Tommy still called it home, but now the game had changed. The Germans had turned from tourists to invaders, and the British were nowhere to be seen. Despite these dramatic changes to his world, Tommy’s childhood experiences had helped him to adapt and turn the new balance of power to his advantage—until now.

No amount of carefully chosen words was going to stop this dog. It seemed to have made up its mind about how to deal with any suspicious-looking locals and was now eating up the last stretch of ground between them at such a frightening speed that Sneum could already see its razor-sharp teeth. He knew he had only a few seconds to come up with a solution, but he was still struggling to understand how the Alsatian had appeared so suddenly. The German guards kept their dogs on leads at all times, so this one had either broken free or been released deliberately by its handler. The guard was nowhere to be seen and the Alsatian was ready to leap. Instinctively, Tommy raised his shotgun and fired. ‘I blew a hole in that animal just in time,’ he recalled. ‘But I also knew straight away that I was still in trouble.’