The Ice Balloon: S. A. Andree and the Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration (18 page)

Read The Ice Balloon: S. A. Andree and the Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration Online

Authors: Alec Wilkinson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #Biography, #History

A few weeks later Andrée wrote Eckholm, “While it should be unnecessary to put forward a question that had already been asked and answered in the affirmative, I feel forced, due to circumstances that you know, to once again ask for your kind and definitive answer to my question, if you are willing to accompany next year’s balloon expedition.” Eckholm wasn’t. Andrée also suspected that Eckholm’s wife had influenced him. In 1895 Eckholm had married a woman named Agnes Boden, who was thirty years old and taught singing and piano.

To a friend Andrée wrote that he didn’t think Eckholm’s leaving would matter. “I don’t think that this needs to give any reason for anxiety regarding the expedition, at least I do not have this feeling.”

At the end of October 1896 Andrée wrote to Alfred Nobel, “I have the sad duty to inform you that Strindberg has rushed ahead and got engaged.” He added that he hoped that Strindberg would not “follow Eckholm’s example.” He felt he could only wait, however, to learn “what face his fiancée, Miss Anna Charlier, will show.”

As a teenager, visiting a family in the country, Strindberg had hidden with some friends behind bushes to spy on several girls who were swimming naked in a lake. When the boys jumped out, the girls ran away. One of the girls was Anna Charlier, whose father was the postmaster in a town nearby. Charlier played piano, and during the years afterward she and Strindberg sometimes played duets. In October, having returned from Spitsbergen, Strindberg was visiting friends in Johannesdal, outside Stockholm. He was staying on an estate belonging to the wife of a rich industrialist who had started a school for disadvantaged children. Charlier was a governess there. Strindberg was having a show of photographs from Spitsbergen. A large group of friends spent the day together then had dinner, and afterward there was music, and they danced. By the time the evening was over, Strindberg saw Charlier differently from the way he had before.

Sixteen days later she was a guest at a dinner at his family’s house. Strindberg had decided that he would ask her to marry him, but being one of the hosts, he was so busy that he didn’t have the chance. She left behind a pair of galoshes, and the next morning, rather than have a servant return them, Strindberg took them to her. She wasn’t up, and he had to wait. They went to a café where they were constantly interrupted by people they knew. Charlier was returning that afternoon to Johannesdal on a boat. On the way to the harbor Strindberg was finally able to ask her.

In the weeks after, Strindberg agonized over how far it was proper to let matters proceed. On one occasion she sat on his lap and her keys fell to the floor, and in reaching for them he was able to touch her leg. “We long for consummation,” he wrote, “and every time we meet it becomes more affectionate. What is the right thing to do? Hold back or give in? I must restrain myself. That is unconditionally the right thing to do.”

Meanwhile, from one of the hundreds of young men who applied to replace Eckholm, Andrée received a letter, “I herewith apply for the position vacated by Dr. Eckholm as the third man on the polar expedition proposed by the Chief Engineer for the next year. I am 26 and a half years of age and have a healthy and strong physique. I have passed my matriculation and graduated from the Royal Technical High School’s Department of Highways and Hydro-engineering. Your obedient servant, Knut Hjalmar Ferdinand Fraenkel, civil engineer.”

Fraenkel was tall and strong and loved being outdoors, and Andrée liked his straightforward manner. His father had worked in construction for the state railway, which meant that he was moved to wherever rails were being laid. Since lines were most often built through countryside, Fraenkel grew up playing in the woods and the fields, and, according to the portrait of him that appears in

The Andrée Diaries

, he developed “a physique which became uncommonly strong and hardy.” He is sometimes described as the expedition’s packhorse. He didn’t drink or smoke. “Excessive enjoyment is the death of pleasure,” is a remark he was fond of.

In school, the report continues, “Knut Fraenkel was no bookworm.” His best subject was gymnastics. When he was a boy an “eye-affliction necessitated his studies being carried on with the greatest caution.” His second-favorite subject was history, and he liked reading about kings and royal exploits, especially those of Charles XII, the king of Sweden from 1697 to 1718, who fought a number of wars. When a friend came to visit Fraenkel in Stockholm and asked to see the town, Fraenkel took him to a park where there was a statue of Charles and had his friend take off his hat before it. Fraenkel had hoped to become an officer, but “an operation for a nervous complaint which he was obliged to undergo had compelled him to change his plans, and to enter the Royal Institute at Stockholm in order to study for his father’s profession.” He had gotten in the second time he applied. When he joined Andrée’s expedition he was hoping to find a place among the engineering corps of the “Road and Water Construction” department.

Fraenkel had never been to the Arctic, and he hadn’t flown in a balloon, either. In April and May of 1897, he went to Paris as Strindberg had and made ten flights, meaning that altogether, by the time the expedition left, its three members had made twenty-seven flights. On one of Fraenkel’s flights the balloon fell so fast that when he and the others threw out sand they were using as ballast it hit them in the face. Fraenkel regarded the experience as fine sport.

Either from genuine fondness or because Andrée felt a persistent obligation to put Strindberg’s family at ease, he spent a lot of time with them during the winter, which annoyed Gurli Linder, who felt overlooked. In a memoir she published in 1935, she addressed him directly, “That winter the Strindberg family had claimed even more of your presence than before. You did not have as much to do for the expedition at the time. You certainly noticed that it was a completely different circle than that to which you previously belonged. We spoke about this a few times the previous winter. ‘You understand that I must show them kindness for Nils’ sake. But they are not at all of the same sort as ours.’ The host”—meaning Oscar—“was a typical bourgeois Stockholmer from the trade association circle, jovial, well-meaning, slightly well-known and a poor writer of poetry. However, it was a moment in which you were relatively pleased, where you were the main highlight around which everything revolved, for which you were admired and fawned over. In our circle you were just one among many equals, here you were the only one.”

Among the regular company at the Strindbergs’ was a singer and actress named Ida Gawell, who performed under the name Delbostintan—she was from Delbos—and Linder felt envious of her. “Happy and witty as she was, it was probably she whose company you enjoyed most,” Linder wrote, “and this was gratefully used by the circle to bring you together as a couple.”

Even so, before he left, she gave him a gold ring with two garnets and a turquoise stone.

Over the winter Alfred Nobel died, unsettling Andrée. Then, shortly before the three explorers left for Spitsbergen again, Strindberg’s father held a farewell dinner, which Andrée was unable to attend because his mother had died unexpectedly—“from paralysis of the heart,” Strindberg’s father wrote, meaning a heart attack—and he was attending her funeral. Strindberg’s father saw Andrée a week later, as the three were leaving, and wrote that he “was as calm as the summer sea.” Privately, though, Andrée grieved deeply. “Now all my personal interest in the expedition has gone,” he wrote. “To be sure, I am still interested in carrying out my idea; I have the same feeling of responsibility for my companions, but of the personal sense of joy there is not a trace. The only thread which bound me to the wish to live is cut off. No doubt all those who start on enterprises like mine, having somewhere a purely individual interest, a feeling of happiness at the thought of some one in whose arms they wish to rest after a completed task, where without reserve they can offer themselves, the essence of their battle, the noblest of their joy. In my case it was only to my mother that this individual interest was attached and you can therefore sense, perhaps, what I have lost.”

Baron Dickson died also. To Dickson’s widow, Andrée wrote, “This is dreadful. Shall I not get any joy from my work? Or does a heavy fate rest over the whole thing?”

Anna Charlier came to Stockholm to spend the last days with Strindberg and his family. It was perhaps during this time that Strindberg took the photograph of her, reclining, that was found in his pocket on White Island. They saw a production of

Lakmé

. The few hours before he left they spent alone. Strindberg was calm until he left his father’s house, “when he burst out weeping for a few moments,” his father wrote. “He is indeed a man, for he left the dearest he has on earth”—meaning Charlier—“to carry out a great idea, and therefore I do think we shall see him back again.”

Charlier held herself intact until she returned to the Strindbergs’ house from the train station, and then she fell into Sven’s arms and wept.

The papers published tributes. One said of Andrée, “Yes, it is you, our hero with the old Viking blood in his veins.” The explorers took the night train to Göteborg. On the platform the cheer “Long Live Andrée” was raised and repeated twice. On May 18 they departed Göteborg on the gunboat

Svenskund

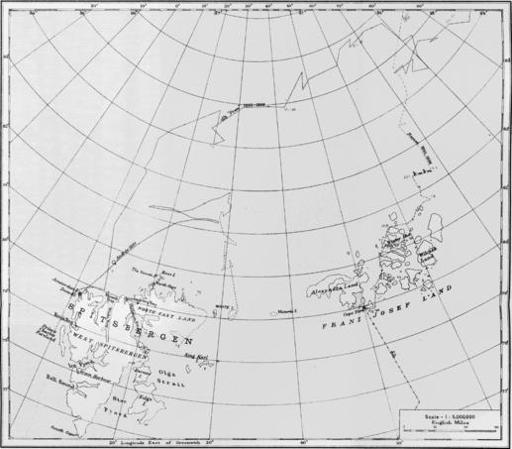

. The day they arrived in Spitsbergen, May 30, a Chicago paper ran a piece that began, “Andrée’s daring in attempting to reach the pole in a balloon is almost certain to cost him his life.” This judgment belonged to a polar expert named Lewis L. Dyche, a professor at Kansas State University.

“His expedition, as an example of daring, has never been equaled,” he said; “it is a piece of stupendous courage, but nature in its most terrible aspect is against him.”

“The theory that the north pole may be crossed in a balloon is extremely fascinating,” Dyche continued, “but the difficulties in the way are almost, if now quite, insurmountable. Nansen’s drift in his boat through the polar currents was completely practicable beside it. Ice and land are tangible things to travel over, but who knows of the currents of the air?

“Andrée’s expedition is most fascinating in its bare possibilities of success, and eclipses that of Nansen in its reckless daring.” Even so, “I am afraid that Andrée’s attempt will be disastrous, although I sincerely hope he will get through all right and land in America.

“The fascination for polar exploration is marvelous. It is a challenge that nature throws down to man. ‘Win the pole,’ she says, ‘and great will be your prize.’ She has awarded prizes for these attempts and the nearer the explorer reaches the pole the greater the prize. Nansen’s prize has been world-wide fame and an ample fortune. Should Andrée succeed in reaching the pole and returning his name will never die and the world will be at his feet. Many men have considered it a prize well worth the attempt.”

The year spent celebrating Nansen had included banquets that Andrée and Strindberg and Fraenkel had attended, and Nansen and Strindberg had spoken often enough to become friendly. To Strindberg, Nansen wrote, “It would be idle, my dear Strindberg, to say that I should not feel a passing pang of jealousy if you should reach the Pole ahead of me. Nevertheless, I wish you success with all my heart. Skoal to the Andrée balloon; and may it solve the great problem in safety.”

Arriving at Dane’s Island in a bay filled with pack ice, Andrée searched the shoreline. “It took longer than I had expected to catch sight of the building,” he wrote. “But finally the upper poles were visible above the hillside and then I could see the two top storeys. What a happy sight that was!”

According to Strindberg, “The balloon house stood when we arrived, but was so damaged by the winter storms that it was on the verge of collapsing. But one must remember that it was only calculated to remain for one summer. With the aid of tackle and buttresses it was soon fixed, and June 14 we brought the balloon from the ‘Virgo.’ ”

Andrée had also returned with a Swedish military officer named Gustaf Svedenborg, who was an alternate to Strindberg and Fraenkel. Over the following days, to varnish the seams, they filled the balloon with air from a huge bellows. The interior of the balloon impressed one man who saw it as being “like the cupola of a mighty church.” Supervised in turn by Strindberg, Fraenkel, and Alexis Machuron, the cousin of the builder and his representative, eight men, with varnish pots and brushes, went over every seam in the upper half of the balloon (being lighter than air, gas would not escape through a lower seam). “The varnish makes the air very bad,” Strindberg wrote, “and after some time one begins to feel a pain in one’s eyes.”