The Ice Balloon: S. A. Andree and the Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration (7 page)

Read The Ice Balloon: S. A. Andree and the Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration Online

Authors: Alec Wilkinson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #Biography, #History

Once Andrée was grown, the only woman for whom he felt a strong attachment was his mother. “Her rich natural endowments, in which good judgment and sharp intellect dominate such characteristics as are commonly called feminine in this day and time, her remarkable will power and capacity for work, as well as her ability to endure and suffer, remind us of the old Norse women,” he wrote in a notebook. “Despite her seventy-five years she does not seem old. Her face has few wrinkles. It seems to belong rather to a woman of sixty. The impression of power still unshaken is heightened by her voice which lacks the sentimental, pleading tone one so often finds in older women. Her voice harmonizes with her exterior: firm, strong, almost gruff, but with an undertone of kindliness.”

A monument, in other words, erected by a child and tended into adult life—which must have been fatiguing. When Andrée felt himself drawn to a woman, what he called the “ ‘heart leaves’ sprouting, I resolutely pull them up by the roots,” he wrote. The consequence was that he was “regarded as a man without romantic feelings. But I know that if I once let such a feeling live, it would become so strong that I dare not give in to it.” An acquaintance wrote in a letter that Andrée appeared to have remained a bachelor for the sake of his mother, and for a while they lived with each other. When Andrée was asked why he had never married, he said of any woman who would be his wife that he would not “risk having her ask me with tears in her eyes to abstain from my flights, and at that instant, my affection for her, no matter how strong, would be so dead that nothing could ever bring it back to life.”

Figures from history occasionally rise up from the page as if they had merely been waiting, sometimes impatiently, for someone to speak to them. Andrée comes to life a little resentfully, as if interrupted. Through his devotion to his mother he may have been restricted emotionally from mature relationships with women. It is also possible that he was indifferent to showing, or incapable of expressing, any true warmth to another person, except in the narcissistic fashion of a child. His great mechanical abilities and inclinations toward solitude suggest a temperament that does not effortlessly engage in conventional exchanges, one that might easily be confused or defeated or embittered, and might find objects and tasks more agreeable than people. Not all of us want the same things from life. The mainstream forces its preferences on the minority, partly to sustain those preferences, but that doesn’t necessarily lend them any substance. Nowhere in Andrée’s writings or in the descriptions of him is there an indication of any but a coldblooded sort of introspection, a capacity for assessing the success or failure of objects and tactics. The territory of feelings seems not to have been hospitable to him.

The only relationship with a woman that Andrée was known to have conducted was an affair with a woman named Gurli Linder, who became in the early twentieth century an admired critic of children’s literature. (Linder wrote the portrait of Andrée in

The Andrée Diaries

.) The affair, which occupied the last few years before he left—Linder in her brief writings on the matter says 1894 was their best and most untroubled year—was conducted so openly that Linder’s husband, a professor, asked her to behave with more restraint lest she embarrass him among their friends.

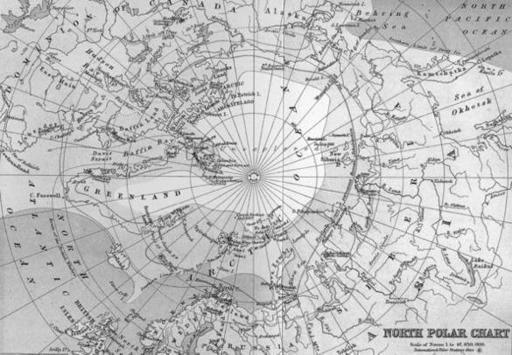

In 1875 an Arctic explorer named Karl Weyprecht, who was from Austria-Hungary, suggested that a series of polar outposts be established by various countries so that science could be done and the results of it shared. Weyprecht felt that polar exploration had become glamorized by its rigors and heroes, and by the pursuit of the unknown at the expense of the intellectual work it might better be doing. Weyprecht’s plan led, in 1882, to the International Polar Year, in which eleven nations established fourteen outposts, twelve in the Arctic and two in Antarctica. Sweden’s outpost was on Spitsbergen. It was overseen by Nils Eckholm, a meteorologist, and, on the recommendation of Professor Dahlander, Andrée’s physics professor, it included Andrée, one of whose tasks was to use a device called a portable electrometer to make notations concerning electricity in the air. The delegation arrived in July of 1882. Andrée was second in command.

No photographs I am aware of show Andrée using the portable electrometer, but from the directions for its use, contained in the paper “Instructions for the Observation of Atmospheric Electricity,” by Lord Kelvin, published in 1901, it is easy to imagine a solitary figure in the daylight of an Arctic summer standing by a tripod about five feet tall. The tripod is not less than twenty yards from any structure that rises above it (“such as a hut or a rock or mass of ice or ship,” Kelvin wrote). To prevent sparks from static electricity leaping from his fur cap or his wool clothes he has covered the cap and his arms with tinfoil attached to a fine wire he holds in the hand that touches the electrometer. The electrometer has its own metal wire to which a lit match is attached, and while the match burns he makes readings by keeping a hair between two black dots, which he has sometimes to squint to see. Andrée performed the task with such resourcefulness, overcoming technical complications that defeated some of the other nations, and so assiduously—he made more than fifteen thousand observations—that the Swedish findings were considered the best among all the nations.

According to

The Andrée Diaries

, “Andrée also endeavored to find a correlation between the simultaneous variations of aero-electricity and geomagnetism. “This has been hard work,” he wrote Dahlander, “for it has been necessary to calculate about 5000 values of the total intensity of geomagnetism.” Meanwhile he made notes about the patterns of drifting snow, which he published in 1883 in “Drift Snow in the Arctic.” Furthermore, to determine whether the yellow-green tinge that appeared in a person’s face at the end of the Arctic winter was a result of the person’s skin having changed color in the dark or of his eyes’ having been affected by the arriving light, Andrée allowed himself to be shut indoors for a month. When he finally went out, it was clear that the pigmentation of his skin had changed. Before his confinement, Andrée wrote, “Dangerous? Perhaps. But what am I worth?” His diligence did not seem to make him well liked, however. His journals often mention that the others are not doing their work properly or are misbehaving, and that he is the only one comporting himself correctly.

“What shall I do when I come home?” Andrée wrote in his journal. In 1885 he was made head of the Technical Department of the Swedish Patent Office in Stockholm, a position he held until he left for the pole. As a kind of ambassador for science and new technology, he traveled in Europe looking for useful patents—he went to the world’s fairs in Copenhagen and in Paris, in 1888 and 1889—especially patents that might reduce drudgery for people who did factory work; he had a social conscience and a conviction that science and new inventions ought to make life less burdensome, that the most useful innovations were applied ones. If people’s lives were easier, he believed, they would be happier, and society would be better, with the result that there would be even more innovations. The man he worked for liked him but thought he was stubborn. He was amused at having pointed out to Andrée that while laws and regulations sometimes prohibited innovations they were nevertheless essential, and having Andrée reply that any law that prevented an innovation was wrong. Andrée’s personality was forceful, and his approach to social and legal change was not subtle. A few years before he left for the pole, he was a member of the municipal council and introduced a motion that the day for people who worked for the city should be reduced to ten hours from twelve, and that the women’s day should be eight hours instead of ten. The proposal failed quickly, and before long, and largely as a consequence, Andrée lost his position on the council.

Between 1876 and 1897 when Andrée left for the pole, the telephone, the refrigerator, the typewriter, the matchbook, the escalator, the zipper, the modern light bulb, the Kodak camera, the gasoline combustion engine, Coca-Cola, radar, and the first artificial textile (rayon) were invented; the speed of light was determined; X rays were first observed and radiation detected in uranium; and Freud and the Austrian physician Josef Breuer began psychoanalysis with the observation in a paper that “Hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences.” Almost quaintly, Andrée embraced modernity by trying to use a half-ancient conveyance in an innovative way.

The first balloon plans patented were patented in Lisbon in 1709 by a Jesuit father named Bartolomeu Gusmão. From a balloon, cities could be attacked, he said; people could travel faster than on the ground; goods could be shipped; and the territories at the ends of the earth, including the poles, could be visited and claimed.

Seventy-four years later the first balloon left the ground with passengers, in France. It was built by the Montgolfier brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne. As children they had observed that paper bags held over a fire rose to the ceiling. Using hot air, their first balloon went up without passengers in the country. Their next went up from Paris with a sheep, a duck, and a rooster, because no one knew what the effect of visiting the upper atmosphere would be, or if there was any air in the sky to breathe. Their third balloon went up with two people. The king wanted the first passengers to be criminals, who would be pardoned if they lived, but he was persuaded that a criminal was unworthy of being the first person in the air, and two citizens went instead.

The hydrogen balloon was developed almost simultaneously by a member of the French Academy named Jacques Charles, who had heard of the Montgolfier brothers’ first balloon and mistakenly thought it had used hydrogen. From the place where the Eiffel Tower now is, he sent up a balloon thirteen feet in diameter, also in 1783. Benjamin Franklin was among the audience. The first balloon to go up in England went up in 1784, and the first to crash, when its hydrogen caught fire, crashed in France in 1785.

George Washington watched the first American ascent, in 1793, by a Frenchman who flew from Philadelphia to a town in New Jersey, which took forty-six minutes. Probably the first ascent north of the Arctic Circle was made by a hot-air balloon in July of 1799, built by the British explorer Edward Daniel Clarke, who was visiting Swedish Lapland. He planned the ascent as a kind of spectacular event, “with a view of bringing together the dispersed families of the

wild Laplanders

, who are so rarely seen collected in any number.” Seventeen feet tall and nearly fifty feet around, and made from white satin-paper, with red highlights, the balloon was constructed in a church, “where it reached nearly from the roof to the floor.” To inflate it Clarke soaked a ball of cotton in alcohol and set the cotton on fire.

The balloon was to go up on July 28, a Sunday, after Mass. The Laplanders, “the most timid among the human race,” Clarke wrote, were frightened by the balloon, “perhaps attributing the whole to some magical art.” The wind was blowing hard, and Clarke thought it would ruin his launch, but so many Laplanders had showed up he “did not dare to disappoint them.” The Laplanders grabbed the side of the balloon as it was filling, and tore it. They agreed to remain in town, with their reindeer, while it was mended. Meanwhile “they became riotous and clamorous for brandy.” One of them crawled on his knees to the priest to beg for it.

When the balloon was released that evening, the Lapps’ reindeer took off in all directions, with the Lapps running after them. It landed in a lake, took off again, then crashed. The Lapps crept back into town.

Hydrogen balloons are absurdly sensitive to air pressure, temperature, the density of their gas, and the weight they have aboard. Pouring a glass of water over the side of a balloon, or a handful of sand, will make it rise. A shadow falling on it will cause it to descend. A balloon has an ideal (and theoretical) equilibrium, at which it would float indefinitely, assuming it didn’t lose gas through the envelope, but that point is impossible to sustain because the balloon’s circumstances keep changing. A rising balloon doesn’t slow as it approaches equilibrium; from momentum, it continues. Having passed the point of stability, it sheds hydrogen, because the gas has expanded as the pressure of the air has lessened, and the balloon sinks, passing the point on its fall. Shedding the perfect amount of ballast at the ideal rate might settle the balloon exquisitely, but shedding weight also causes the balloon to rise. If it rises too quickly the only corrective might be to release hydrogen, which the pilot would rather retain. Part of the skill of flight, particularly of a flight that is to last a long time, is to manage the altitude with sufficient temperance that little gas or ballast is lost. Enough ballast must be kept to land the balloon properly. Theoretically a balloon might be operated more stably at night, since the temperature does not change as clouds intersect the sun.

Someone traveling in a balloon never feels the wind, or hears it, because he is advancing at the same speed. Early aeronauts, enclosed in silence, used to feel not so much that they were moving as that the land below them was approaching.