The Indian Ocean (47 page)

This is a convenient place to present some random data on speeds at sea, before going on to the other two technological matters, the Suez Canal and ports. It will be remembered from the previous chapter than a good speed for a sailing ship was up to 200 km a day (see pages 186–7). In the nineteenth century ships in the Great Southern Ocean, scooting along before the westerlies, could achieve over 500 km a day.

65

Tim Severin's replica dhow usually made about 140 km a day. The huge barques carrying bulk cargoes from Australia to Europe went very fast in the Great Southern Ocean and elsewhere, partly to save costs and partly as they were racing each other to get to Europe first. One of them in the southern Indian Ocean covered, very dangerously, 126 miles (225 km) in eight hours, the equivalent then of 675 km in a day.

66

Villiers wrote that one could expect to do about 470 km a day between the Cape and Australia, about the same speed as the great VOC ships in the seventeenth century. Modern specialist yachts do much better. In late 2001 one of the boats in the Volvo Round the World race in the southern ocean set a record by covering 640 nautical miles (1150 km) in one day of very heavy sailing. This is an average of 26.6 knots. The fastest sailing vessel on record was a trifoiler which in 1993 reached 46.5 knots over a 5,000 metre course.

These however are exceptional speeds. Further north, in the monsoon zone, times were slower, but still much faster than those claimed by Braudel for the Mediterranean. Generally speaking, with a good wind a ship could make 150 km a day. Yet without a favourable wind things could be very slow. In 1822 Fanny Parks's ship, near the equator, made only 17 nautical miles, 31 km, in a whole day.

67

Passages on inland waterways could be slower still. Emily Eden's 'flat', that is a large barge towed by a steamer, averaged only 36 km a day and was constantly bumping on the banks and going aground.

As a rule of thumb, late nineteenth century cargo steamers averaged 10 or 11 knots, the mail steamers up to 18, with 15 knots, that is 15 nautical miles an hour, resulting in a distance over a day of 650 km.

68

Particular circumstances could alter this drastically. Isabel Burton travelled on an Austrian Lloyd ship which went only 8 knots, the reason being, so she darkly noted, that 'the captains have a premium on coal'. Ships in the Suez Canal also had to go slower. Burton passed through in 1876, when it was just opened. Ships could travel only in daylight, and the top speed was less then 6 knots.

69

Gavin Young had an interesting voyage on a local craft from Colombo to the Maldives in 1979. The launch he was on made only 6 knots, and was wildly overloaded with a cargo of lavatory seats and bowls, chairs and tables. The crew, as is still commonly done on small craft in the Indian Ocean, had a sail and used it when the wind was favourable.

70

The triumph of steam, if this be not too grand a term, was strongly facilitated by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. As Isabel Burton put it, 'it is the last link

riveted in the great belt of trade, and the road for our ships is completely defensible.'

71

In combination with steam the results were dramatic and rapid. Both the numbers of ships which transited, and their sizes, grew exponentially. The average size of ships transiting was 1,510 tons in 1880, but 5,600 tons in 1938. Total transits were 486 ships in 1870, in 1880 it was 2,026, in 1890 it was nearly 3,389, in 1900 it was nearly 3,441, in 1910 it was 4,533, in 1920 it was 4,009, and in 1930 it was 5,761. A year after the opening shipping through the Canal was 436,000 tons, in 1875 it was 2 million, in 1895 it was 8.4 million, and in 1913 it was 20 million. The tyranny of distance was greatly reduced. London to Basra via the Cape was 11,440 nautical miles, via Port Said 6,700. To Mumbai was respectively 10,780, and 6,370, to Kolkata 11,810 and 8,020, and to Fremantle 10,960 and 9,640. Put in other terms, the savings in terms of distances to be travelled were: London to Mumbai 42 per cent, to Kolkata 32.6 per cent, Fremantle 14.3 per cent, Kuwait 42.5 per cent, Singapore 27.8 per cent.

72

The main user was always Britain, and as Burton noted it was a vital link in the imperial system. The British occupied Egypt in 1882 in order to ensure British control of the canal. To the late 1880s nearly 80 per cent of the ships using the canal were British, and indeed from its opening until 1934 British ships in every year made up at least 50 per cent of the total. The central strategic importance of the canal also led to Disraeli's purchase of Egypt's shares in 1875, after which Europeans owned 99 per cent of the total shares of the company which ran the canal. Most of the employees of the company were European or Americans, as were thirty out of the thirty-two directors. The directors were paid very generously, and the British government also did well out of its shareholding. They paid £4 million in 1875, and received dividends of £86 million between 1895 and 1961.

73

The indirect advantages to the British were less easy to quantify, but were massive. The canal facilitated trade, made possible faster communications with the heart of the empire, India, and rapid movement of troops from the metropole to the colonies. The reciprocal nature of the enterprise is perhaps best seen in the way Indian troops were used in 1882 to help the British take-over of Egypt, and in 1885 in the Sudan. Other consequences were legion. The canal assisted in the demise of sail between Europe and the Indian Ocean, and the Cape route became less profitable. Steam and canal were linked, while sailing ships could not use this narrow water way. Cape Town became isolated and less important in the imperial system, while east and southeast Africa were now drawn more closely in. The Red Sea route, which had been eclipsed by the Cape route since the sixteenth century, revived: steam ships calling at Jiddah rose from 38 in 1864 to 205 in 1875.

74

Islands in the Indian Ocean – Madagascar, Comoros, Mauritius – once used as way stations for shipping using the Cape route, were now less important.

There was a symbiotic connection between the three elements we have delineated. Steam ships became bigger and bigger, and this was made possible by, and also required, the progressive deepening and widening of the canal. Similarly, bigger ships needed better ports, or on the other hand better ports made possible bigger ships. An engineer in 1910 vividly described this as a race:

A race between engineers: such might describe the condition of affairs in the maritime world of today in regard to two of the most important branches of civil engineering. On the one hand, we have the ship designers turning out larger and larger vessels; on the other is the harbour engineer, striving vainly to provide a sufficient depth of water in which to float these large steamships. It is a tremendous struggle. The former has set the pace, and the latter finds it hot, so much so that he is hard put to it to keep on his rival's heels.

75

We have had occasion to notice how difficult were many of the ports around the ocean before the nineteenth century. The Coromandel coast was notoriously dangerous; Kolkata and Jakarta, both vital centres, were located on treacherous estuaries. An American visitor described Jakarta in the 1830s:

The mode of landing in Batavia is not common. The water in the roads is so shallow that ships lie about three miles from the shore. . . . There are two booms, formed of wooden piles, extended seaward, for a mile, in a straight line from the shore, having a canal between them; at the entrance of which, the sea breaks over a sand bar, with such violence at times during the north-west monsoon that boats are frequently upset and the passengers are subjected to a narrow risk of becoming food for sharks and alligators, even if they escape drowning.

76

To get ashore in Chennai was, as we have noted already, a real obstacle course. In June 1765 Mrs Kindersley wrote despondently that 'I am detained here by the tremendous surf, which for these two days has been mountains high: and it is extraordinary, that on this coast, even with very little wind, the surf is often so high that no boat dares venture through it; indeed it is always high enough to be frightful.'

77

Kolkata, being far up the delta of the Hughli, had no surf, but it had other perils. Mrs Kindersley, once she was able to leave Chennai, next wrote to a friend:

At length I have the satisfaction to inform you of our arrival at Calcutta. The voyage from Madras, short as it is, is a dangerous one; for the entrance to the mouth of the Ganges is a very difficult piece of navigation, on account of the many islands, cut out by the numberless branches of the river; many of which branches are really great rivers themselves, and after sweeping through and fertilising the different parts of several provinces, there disembogue themselves, with great force, and the roaring noise of many waters. Besides there are a number of sand banks, which, from the prodigious force of the waters, change their situation. Therefore it is necessary to have a pilot well skilled in the different channels; but as such are not always to be had, many ships are thereby endangered, and sometimes lost.

78

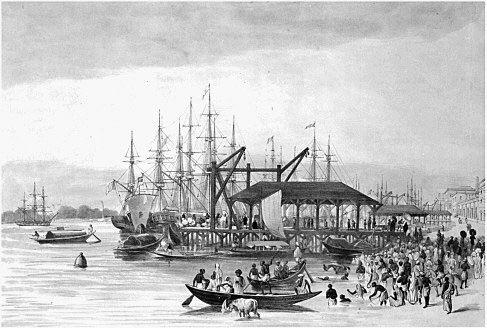

Figure 5

Custom House Wharf, Calcutta. Produced by Sir C. D'Oyly (artist) and Dickinson & Co. (engravers). © National Maritime Museum, London

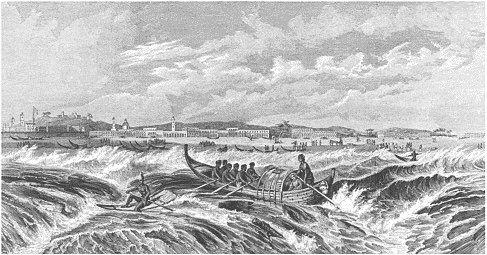

Figure 6

Madras. Produced by Leighton (artist) and William Measom (engraver), c. 1848. © National Maritime Museum, London

In 1845 Fanny Parks left Kolkata, being towed by a steamer, yet even so the passage nearly defeated them. 'At 8 a.m. while we were in tow of the steamer the

Essex

ran upon a sandbank; she fell over very disagreeably on her side, was thus carried by the violence of the tide over the obstacle, and righted in deep water.... The pilot was much surprised, as a fortnight before that part of the river was all clear.' The rush of the tides was a real hazard: 'This evening the tide ran with such violence that after the vessel had anchored, it was necessary for a man to remain at the helm. This steering an anchored vessel had a curious and novel effect.'

79

Macabre sights added to the distress of the traveller. Up river from Kolkata in 1810 Mrs Graham described how

The other night, in coming up the river, the first object I saw was a dead body, which had lain long enough in the water to be swollen, and to become buoyant. It floated past our boat, almost white, from being so long in the river, and surrounded by fish; and as we got to the landing-place I saw two wild dogs tearing another body, from which one of them had just succeeded in separating a thigh-bone, with which he ran growling away.

80

Clearly all this was quite unsatisfactory. New ports had to be created to facilitate the movement of people, and especially of goods. The main ports to serve the steam ships were Aden, Mombasa, Mumbai, Karachi, Colombo, Chennai, Kolkata, Singapore, Fremantle and Jakarta, and then others in East Asia and eastern Australia. Jakarta is a good example of what the imperialists did. As we saw, the approach was quite impossible. Silt from the river Tjiliwong, on which it was located, meant that the foreshore extended by over 20 metres a year! The rapid rise of Singapore after its founding in 1819 was disastrous for Jakarta. As Earl noted in 1832, Jakarta

was formerly visited by numbers of large junks from China and Siam, and by prahus from all parts of the Archipelago; but since the establishment of the British settlement at Singapore, the perfect freedom of commerce enjoyed at that place has attracted the greater part of the native trade, while that formerly carried on by junks between Jakarta and China has totally ceased.

81