The Indigo King (8 page)

Authors: James A. Owen

“This is Jules Verne?” John asked, flabbergasted. “He’s dead?”

“The world we knew thought he died in 1905 anyway,” said Bert, “and he may well have. But he had a lot of traveling around to do, in time as well as in space, and he had the bad fortune to end up here, with me, in this dismal place.”

“What happened?”

“Mordred was waiting for us,” said Bert. “He knew we were coming, somehow, some way. And before we could gird ourselves up to work out what had happened to us—hell’s bells, to the whole bloody

world

—Jules was killed.”

“There was no way to contact the Archipelago for help?” Jack asked, taking the skull from John and hefting it in one hand. “Samaranth, or Ordo Maas? Anyone?”

Bert shook his head and looked at Jack intensely. “You still don’t get it, do you, boy? In this place, there is no Archipelago! Mordred destroyed it all centuries ago, and then set about destroying this world as well! The only creatures or lands who survived were those who joined him, like the giants and the trolls! Everything and everyone else—dragons, elves, dwarves, humans … all gone! There was no way to contact anyone, and no one to hear the call if there had been a way!”

“Could you have used the Serendipity Box?” asked Jack.

“I did use it,” Bert said, sitting again. “And as Jules had said it would, it gave me what I needed. At least,” he added, “I hope it did. Only time shall tell.”

“I don’t know what all the fuss is about,” said Uncas. “There’s nothing but crackers in here, anyway.”

The others turned back to the table to see the box, top flung wide, spilling over with oyster crackers. Uncas was happily shoving them into his mouth with both paws, while Fred stood a few feet away with a horrified expression on his face.

John took a bowl from a cupboard and emptied the box into it, then closed the box and replaced it on the mantel, higher than a badger’s reach.

“Oh, great,” Jack groaned. “We have one chance each to get something miraculous from that box, and Uncas wastes it on crackers.”

“It doesn’t work like that,” Bert said with a chuckle. “It isn’t a magic genie’s bottle that you rub to get three wishes. It gives you, and you alone, one time, what it is that you need the most. So,” he finished, rubbing Uncas on the head, “it’s likely that it doesn’t matter when or where or how Uncas opened the box. It would probably have been full of oyster crackers just the same.”

“Forry,” said Uncas through a mouthful of crackers. “I juff willy wike ‘em.”

“I think you might be correct,” Bert mused, turning to John. “I think perhaps Jules had planned ahead for something only he was privy to. Something that’s happening right now.”

“Hold on, you old goat,” Chaz said, still glancing out the window and fidgeting nervously. “Don’t go gettin’ any ideas.…”

“But don’t you see?” Bert exclaimed. “If all of this was fore-told—was anticipated—by Jules, then that changes everything!”

“What are you talking about?” asked John.

“The Serendipity Box was left for you, John. Jules left it for you, and Jack, and Charles. He said you’d come for it. I just never imagined it would take fourteen years.”

“I’m surprised Mordred didn’t take it for himself,” said Jack.

“He did,” Chaz answered, gesturing to his face. “He opened it, then flew into a rage at whatever it was he saw inside. Then he tried to burn it, but I managed to steal it back. That was the day I got these scars.”

“Mordred didn’t know the box can’t be destroyed,” said Bert. “I’ve kept it here since, waiting.”

“He does have a habit of trying to burn things that can’t be burned,” said Jack, clapping Chaz on the back. “Well done, old boy.”

“We met,” Bert said, indicating Chaz, “using the same logic you used to come here. I went looking for you, as you came looking for me. For better or worse, I found

him

.”

Chaz made an obscene gesture and looked out the window again. “Sky’s brightening. Sun’ll be up, soonish.”

“We’re together again, is what matters,” said Jack. “Any reunion of friends is a good happening.”

But John was not nearly so pleased. He was putting together parts of the puzzle that made more sense to him than he liked, and he was slowly realizing that as safe as they felt at that moment, they might in fact be in greater danger than ever. There was a connection of some kind between Chaz and Mordred that had not been revealed. But there was one question on his mind that was even more terrible.

“Bert,” John intoned dully, “why were

you

spared? Why was Verne killed, and not you?”

Bert closed his eyes and sat silently for a long moment before answering.

“Because,” he finally said, “it was what had to happen.”

“Practicality,” said Chaz. “You did what you had to do.”

John stood up and backed toward the door. “What did you do, Bert?”

“What I was destined to do,” Bert replied, his face gone cold. “I just never got thirty pieces of silver.”

“You sold him,” Jack whispered. “You sold Verne to Mordred, to save yourself.”

“I won’t argue that on the face of it,” Bert said plaintively, “but I take exception to your implication. I did what I had to do to survive to this point in time—but it was not of my own volition, and I compromised myself greatly to do so. I’ve made many more compromises since, all to make certain that we would be here, tonight, to have this very conversation. So were my actions virtuous, or shameful?”

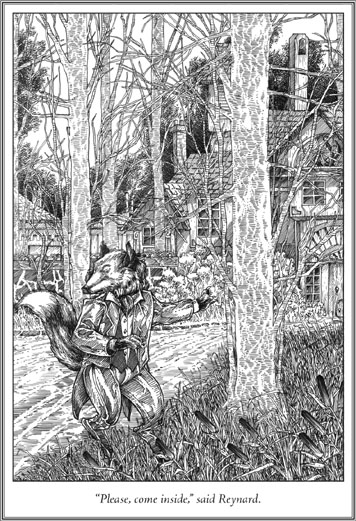

“That,” an icy voice said from just outside the door, “depends entirely on one’s point of view.”

Noble’s Isle

All of them save for Uncas and Fred recognized the voice immediately.

“May I come in?” it said, in a tone that made it sound more like a statement than a query.

Bert sighed heavily. “Enter freely and of your own will, Mordred.”

The door opened, and silhouetted against the rising sun they saw the imposing figure of the man they had known as the Winter King. The man they had caused to be killed. The man who, more than once, had tried to kill

them

. And their most trusted ally had just invited him into his house.

Mordred was not significantly different from when they had seen him in their own world. He seemed perhaps more aged, more weathered here. He was stouter, and slightly round-shouldered, but his arms were corded with muscle, and his hair cascaded down his back in a mane. He was dressed in royal colors and had the bearing and manner of a king.

He was in appearance, John realized with a shock, everything one would expect a king to look like, to emanate. And he suddenly understood how a man could be a tyrant and still rule: It was a question of the ability to command, to draw respect, even in the wake of evil acts.

Immediately John and Jack took defensive stances in front of Bert and the badgers, but Mordred ignored them, leaning casually against the door frame and addressing Bert.

“My old friend, the Far Traveler,” the king said. “We meet again.”

Bert glared at him. “Nothing going on here concerns you, Mordred,” he said, gripping the staff so tightly his knuckles turned white. “You needn’t have come.”

“Oh, but everything in my kingdom concerns me,

Bert

,” Mordred replied. John and Jack, still facing their enemy, didn’t notice the blood drain from Bert’s face at the mention of his name. “The citizens who walk my streets, as well as the Children of the Earth who live beneath them.”

This last he said to Uncas and Fred, who both hissed at him in reply. They did not need to have seen him before in the flesh to realize they were facing the greatest adversary of legend, whom Tummeler had told them about.

For his part, Bert simply slumped in the chair, his chin resting on his chest. He seemed already defeated in a game where the stakes had not even been named. “Why are you here, Mordred?”

“Why?” Mordred replied in mock surprise. “I have simply come to meet the two new friends I have waited to meet for so very, very long.”

Waited to meet? John thought. Had Bert given them up as well? John looked at his mentor, but the old man simply continued staring at the king.

“That’s very bold, to come here alone,” Jack said to Mordred, taking the lead in the game being played out in the shack. “Maybe you don’t have any memory of it, but we have all clashed before and seen you bested in battle.”

“Is that so?” Mordred purred condescendingly. “What battles were these?”

“I beat you on the ocean, with a ship called the

Yellow Dragon

in the Archipelago of Dreams, and he,” Jack said, gesturing at John, “beat you in a swordfight.”

Technically, everything Jack said was true—although there had been luck and allies aiding him in the sea battle, and John had not precisely won the swordfight. Either way, the bravado didn’t faze the king.

“I think not,” Mordred said, smiling. “At any rate, the loss of a battle is not the loss of a war—or its victory, either.”

“You’ve certainly learned a few things,” John said. “There’s no disputing that. It’s a shame it didn’t make you a better ruler.”

“Whether I am a better ruler than others might have been is not for you to judge. There is only one man who ever lived who was fit to judge me, and he—”

Mordred stopped, almost violently, as if he had spoken too openly. “All that is important to a ruler,” he continued, “is strength, and mine has been more than sufficient for a very, very long time.”

“Bold words, given the odds,” said Jack. “I count four to one.”

“Five, if you stack the badgers,” said John.

“I count far fewer than that,” said Mordred. “The Far Traveler—Bert, is it?—really only counts for half, don’t you think? And the animals are even less to me. So that makes it even, doesn’t it, Chaz?”

Uncas and Fred let out small howls of dismay, and Bert’s head dropped farther to his chest.

John looked at Chaz, astonished. “Don’t tell me you’re taking his side.”

Chaz refused to respond—which was response enough.

“Of course,” Jack spat, clenching his fists. “He’s like the Wicker Men—a lackey and a traitor. He was going to sell us out to the Winter King all along.”

It was Bert’s turn to be surprised. “Chaz!” he exclaimed in shock. “Why? Why would you do that?”

“You’ve always known how I gets by,” Chaz shot back. “It never bothered y’ before.”

“It always bothered me, Chaz,” said Bert. “I know you’re better than this. I always have.”

“That wasn’t me you knowed,” said Chaz. “That was some other bloke called Charles. Not me.”

“But … but …,” Bert sputtered, “you knew I was looking for them. Why would you sell them out to Mordred, only to bring them …” His voice trailed off, and he let out a despairing breath. “You gave him my name too, didn’t you, Chaz?”

“Actually,” put in Mordred, “a little bird told me. Hugin. Or Munin. I forget which. Ravens all look alike to me.”

“What’s in a name?” Jack said, breaking through the pall that had settled over the room. “Calling Chaz ‘Charles’ wouldn’t make him less of a traitor, so why does it matter whether or not Mordred knows

your

name?”

“True names are imbued with power—and knowing someone’s true name gives you some of that power yourself,” Mordred said in response. “Enough, at least, to do what must be done. Am I correct, Far Traveler Bert?”

“That’s what you did,” John said to his old mentor. “You told him Verne’s name, and somehow Mordred used it against him.”

Bert seemed caught somewhere between lashing out in anger and bursting into tears. He sat, trembling, and glared at Mordred and Chaz.

Mordred chuckled and turned around, his hands clasped behind his back. “That was it, and that was all, and it was enough … ah, what did you say your name was again, child?”

“That be Scowler John y’ be addressin’!” Uncas exclaimed.

“Uncas, no!” Jack shouted before realizing he’d just made the same unwitting mistake by blurting out the badger’s name. “Oh, damnation,” he muttered. “Sorry, John, Uncas.”

Mordred chuckled again and raised his left hand to his mouth. He bit into his thumb, hard. Blood welled into the torn flesh and he turned around, eyes glittering.

“Don’t apologize t’ me,” said Uncas, who clearly was the only one in the room who did not realize what was transpiring. “A king might talk t’ Fred an’ I like that, but he should respect men like you, Scowler Jack.”

John slapped his forehead in resignation. The Winter King now had all their names. And the hapless Caretaker already anticipated what was coming next.

Before any of them could react, Mordred moved, almost faster than they could follow, first to Jack, then, surprisingly, to Chaz, then John, then the others. He marked them each on the forehead with the blood from his thumb, and as he did so, he called them by name: “Jack and Chaz, John and Bert, Uncas and Fred—I am Mordred the First, thy king.”

Then, he began to recite words John did not realize Mordred knew:

By right and rule

For need of might

I thus bind thee

I thus bind thee

By blood bound

By honor given

I thus bind thee

I thus bind thee

For strength and speed and heaven’s power

By ancient claim in this dark hour

I thus bind thee

I thus bind thee.

The instant Mordred began speaking, all the companions found themselves unable to move; their arms felt bolted to their sides, their jaws fixed and unmoving. All, that is, save for one.

Mordred finished the Binding and once more looked at each of them in turn. He was triumphant, but there was a trace—the merest trace, John thought—of melancholy in his expression.

Of regret.

“Long ago there was a prophecy,” Mordred began, “that mentioned someone called the Winter King. It was said that he would bring darkness to two worlds, and that …” He paused, considering, then continued. “It said that three scholars, three men of imagination and learning from this world, would bring about his downfall.

“It was more than a thousand years before some among my people began to call me by that name—and only then did I remember the old prophecy.

“The prophet never mentioned the Far Traveler, but when he and his companion first came here fourteen years ago, it rekindled the possibility that the prophecy was true. And so since then I have waited patiently for the three scholars it spoke of to arrive: John, Jack, and

Charles

.”

This last he said with a wink at Chaz. “Not precisely what had been prophesied, but when the Far Traveler sought you out, I saw a possible connection and decided not to take chances. And when you sent word that you’d found these two, your own fate was sealed.

“My Shadow-Born will attend to you all shortly. We shall not meet again.”

Mordred spun about as if to leave, then thought better of it and stepped slowly back to where Jack was standing.

“I was not always as you see me, child,” he whispered. “I

was

different, once.…”

Frozen in place, Jack could not respond, and after a moment Mordred took a step backward, turned, and opened the door. They heard him striding across the bridge, then nothing. He was gone.

The Binding was absolute. There was no way to move or speak. But it was not so complete that it did not allow tears to flow, and Bert wept. So did Jack, but more from frustration than sorrow. Chaz was still too stunned to weep; and John’s mind was racing too fast to stop and worry over the desperate situation they were in. Even without the Binding, Fred would have been petrified by fear. A blood marking was a potent thing, and even more so among animals than men. Combined with the Binding spell, it was impossible to overcome. And so none of them were able to turn around to see what was making the crunching noises under the table.

“Oh, bother,” Uncas said. “That’s all the crackers, gone. If I’d known we were going to become prisoners, I’d have saved some of the soup, so as not t’ die on an empty stummick.”

Uncas was unfrozen. The Binding had not affected him at all. He continued complaining, all the while rubbing worriedly at the small silver coin he’d had in his pocket.

Of course

, John thought.

Bindings may be broken by silver! Uncas must have been touching the coin, and so he wasn’t frozen. There might still be a way out of this after all

!

John’s initial rise of hope quickly dropped as he realized that Uncas being free might not be such a big advantage. The badger still had not realized that the rest of them could not move.

“Y’think he’s gone?” Uncas asked, peering over the bottom of the windowsill. “What d’you think that blood-marking business was about, anyhow?”

When no one replied, Uncas scurried over to his son, finally realizing that something was amiss. “Fred? What is it? What is it, son?” he asked. “Fred? Can’t you answer?”

Fred couldn’t, and didn’t, and the reality of what had occurred finally dawned on Uncas. And then he did the only thing he could think of, and consulted the Little Whatsit.

“Hmmm hm hm hm hmm,” Uncas hummed as he flipped through the pages. John had just enough range in his field of vision to see the pages below. The badger seemed to be following some arcane indexing system based on keywords.

“Spells, curses,” Uncas murmured, chewing absently on the coin, “also see: Bindings, counterspells, blood-oaths, and … ah, yes, here we go. It’s under the section on blood. You know, it be a fascinatin’ thing … I never would have made th’ connection to lycanthropy, but …”

Uncas blinked, then looked at the coin. “Well, pluck my feathers,” he said. “Silver’s good for lots o’ stuff.”

He repeated the process Fred had performed earlier, grinding the coin to a fine powder. Then, apologizing for the presumption, he sliced five shards of wood from the ash staff, moistened them with his tongue, then rolled them in the silver dust.

“Let’s try this with you first, Fred,” he said to his son. “If it works, y’ can help with th’ others.”

Uncas closed his eyes and murmured a badger’s prayer under his breath, then plunged the ash and silver dart into Fred’s forearm.

It worked.

“Ow!” Fred yelped, rubbing at his arm. “Good show! The Royal Animal Rescue Squad, trained an’ true!”

The remedy worked equally well on the men. “Sort of a reverse Balder, eh, Jack?” John asked, examining the dart. But Jack wasn’t listening. The second he was freed, he had Chaz pinned to the wall.

“Why did you do it, Chaz?” Jack shouted, livid. “Was it really worth selling out your friends for a few lights?”

“You in’t my friends!” Chaz howled in reply. “Besides, he froze me the same as you!”

“No time! There’s no time for this!” Bert exclaimed. “Mordred’s minions are everywhere, and the news we’ve escaped may reach him any moment—and then we’ll all be lost!”