The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (8 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Much of the news communicated in medieval society was still a matter of the spoken word, and thus frustratingly often lost. We have to delve into other sources, such as chronicles, to attest the lively interest in receiving and sharing news. The one main exception, which has been left to its own chapter, is the correspondence generated by the growing international network of trade. Long-distance commerce of necessity separated merchants from their partners and agents. They had, therefore, to develop systems of sharing news, in an atmosphere of trust, and with a reasonable expectation that their correspondents would act on the information. It was a critical development in the history of news gathering.

CHAPTER 2

The Wheels of Commerce

W

HEN

one considers the problems and expense that Europe's crowned heads experienced in keeping abreast of events – and how often they failed to do so – the smooth, efficient progress of merchant correspondence provides a vivid contrast. Between 1200 and 1500 the economy of Europe was transformed by the rise of the great merchant companies, trading between Italy and northern Europe, Germany, the Mediterranean and the Levant. The appetite for eastern luxuries, spices and costly fabrics, exchanged for northern wool and cloth, created a large and expansive marketplace, full of opportunity for the bold and ingenious trader. The hazards were also obvious. A ship could be lost at sea, consignments of goods waylaid on Europe's perilous roads. The intricacies of the money markets created new complexities for those who failed to master the ever-changing exchange rates. And politics – war, dynastic conflicts or civil disorder – could derail even the most carefully managed enterprise.

To succeed in this labyrinthine and unpredictable world, merchants had to remain informed. In the thirteenth century a certain class of merchant ceased to travel with their goods and instead attempted to manage their business through brokers and agents. At that stage the growth of a network of merchant correspondence became inevitable. The essential building blocks were already in place. Unlike the princes, who had to create such a network from scratch, merchants had ships, and a far-flung network of agents and warehouses. Carts, couriers and pack animals passed back and forth every day between Europe's major trading towns. They carried with them news and, increasingly, written correspondence.

Even so, the volume of this correspondence is breathtaking. We get a flavour of its magnitude by examining the well-documented example of Francesco Datini, a merchant of Prato in Tuscany. Datini was never a member of one of the great merchant families. A self-made man, he had amassed his fortune

trading in armaments in Avignon before returning to his home town in middle age. Operating through a series of ad hoc partnerships, he consolidated his wealth by shrewd diversification into banking and general trade. Between 1383 and 1394 he established branch offices at Pisa, Genoa, in Spain and Majorca.

1

For all this Datini remained a man of the second rank: his fortune, when he died in 1410, was a respectable 15,000 florins. Yet he also left behind five hundred account books and ledgers, several thousand insurance policies, bills of exchange and deeds, and a staggering 126,000 items of business correspondence.

2

Thanks to this survival (the childless Datini left all his property to the local poor) they comprise one of the greatest archives for understanding the international medieval economy.

That a middle-ranking merchant could accumulate such an extraordinary documentary archive seems highly exceptional, but in its day it was probably routine: the Datini archive was unusual only in its survival. It was contingent, however, on one further technological revolution, as significant in its way as any other of the medieval period: the introduction of paper. Parchment (often known as vellum), made from scraped animal skins, had served the medieval world well. It was hardy, took ink smoothly and evenly, and was very durable, as witnessed by the quantities of parchment documents that survive today. Parchment was also, to an extent, reusable. But it was brittle, and could not easily be folded. It had to be cut from the shape of the skin, with considerable waste from trimming. It was also expensive. The raw material was finite, and took a long time to prepare. The volume of documentation generated by commerce and the expanding state bureaucracies demanded a more flexible and cost-effective writing medium.

Paper entered Europe via Moorish Spain in the twelfth century. Within a hundred years paper mills had been established in Italy, France and Germany. The technology, though capital intensive, was relatively simple. Paper-making demanded an abundance of linen rags and swift running water to power the mills that pounded the rags into mulch. Paper mills were usually constructed in hilly regions close to major centres of population. By the thirteenth century they were turning out a sophisticated range of paper products in carefully graded weights and sizes. Parchment continued to be preferred for precious documents intended to be preserved: charters, deeds and manuscript books. Paper also took longer to enter general use in northern Europe, where the raw materials were harder to come by, because in the colder weather people wore clothes made of wool rather than linen. In England there was no domestic paper manufacture until the eighteenth century, so all paper had to be imported. But despite this, by the fourteenth century paper was the preferred medium for all mundane purposes of record-keeping and correspondence

throughout Europe. This humble artefact had established the dominant role in information culture that it retained into the last decades of the twentieth century.

In Bruges

The northern axis of the great network of European trade was Bruges, the vibrant Flemish city that still retains much of its medieval charm. Bruges was the hub of the trade in wool and cloth. To this city came the finest English wool, from whence it was either shipped south or manufactured into the high-quality dyed Flemish cloths which commanded a high price in Italy, France and Germany. All the major Italian trading families of Genoa, Venice and Florence maintained offices in Bruges. Its great square provided space for the exchange of goods from all over Europe.

The fortunes of Bruges were assured with the arrival in 1277 of the first Genoese seaborne fleet.

3

The groups of foreign traders who settled in the city were organised into separate nations, each with their own residential headquarters and charter of privileges. The Italians were particularly numerous. At a time when Italian overseas trade was dominated by the so-called super-companies, each was heavily represented in Bruges.

4

Technically nothing could be sold in Bruges except through a licensed native broker. Although this stipulation was frequently evaded, brokerage fees yielded large gains for local men. Managing the enormous demand for monetary instruments was also lucrative. By the fourteenth century Bruges had become, in effect, a highly sophisticated service economy. It was also the largest money market in northern Europe.

5

Communications played an essential role in oiling the wheels of trade. Though many of the bulk goods from southern Europe continued to be transported by sea, letters were sent overland. They travelled along the settled routes familiar to pilgrims and the first generation of international traders in the twelfth century. The roads from Bruges to Italy were recorded in handwritten itineraries which guided the traveller in carefully delineated stages between the largest towns. From Flanders the road went either east to Cologne and down the Rhine, or south to Paris, and thence, via the plains of Champagne, to the Alpine passes.

6

The merchants and travellers who met on these routes would inevitably exchange news. Pilgrims could also sometimes be persuaded to carry letters with them on their way home. But the sheer volume of documentary traffic demanded something more settled and permanent. In 1260 the Italian merchants set up a formal courier service between Tuscany and Champagne,

home at this time to the most important of the great medieval trade fairs. The rhythms and itineraries of trade were built around these fairs. Merchants were enticed to do business by the promise of a large international gathering. Cities competed for the valuable business by offering exemptions from customary dues and tolls in transit. The fairs of Champagne offered a fixed sequence of markets that lasted through most of the year from spring to autumn.

7

They were the centre of a European network that spread out through the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries to embrace Geneva and Lyon to the south, St Denis north of Paris, and Frankfurt in Germany. Further afield lay Leipzig, Medina del Campo in Spain and Antwerp, the rising rival to Bruges in the Netherlands. Fairs provided the opportunity for face-to-face bargaining and the exchange of information. Much of this commercial and political news was never committed to paper. Merchants had to have a highly developed capacity to retain information on commodity prices, exchange rates, distances and commercial rivals. A good memory was a precious financial gift and one that was consciously trained and nurtured. The account book of Andrea Barbarigo of Venice records in 1431 a cash payment of 13 ducats to ‘Maistro Piero dela Memoria for teaching me memory’.

8

In the fourteenth century the wealthier merchants travelled less. Although the fairs still attracted merchandise, much bulk commerce was now shipped by sea. This only increased the need for reliable intelligence. In 1357 seventeen Florentine companies banded together to create a shared courier service. The most important routes ran from Florence to Barcelona, and from Florence to Bruges. The Bruges service ran along two routes: one via Milan and then up the Rhine to Cologne; the other diverted from Milan via Paris. The rival

scarzelle Genovesi

ran services from Genoa to Bruges and from Genoa to Barcelona.

9

In addition to the trans-continental routes, the Italian merchant communities established numerous shorter-distance services within the Italian Peninsula. A twice-weekly service ran between Venice and Lucca. The weekly post between Florence and Rome arrived in Rome on a Friday and set off back on Sunday. It was now only a short step to the establishment of commercial courier services, run on behalf of the merchant companies by independent entrepreneurs. The firm headed by Antonio di Bartolomeo del Vantaggio in the fifteenth century operated a whole network of routes, including a weekly service between Florence and Venice.

Couriers were expected to keep to strict timetables. In the 1420s couriers from Florence were expected to reach Rome in five or six days, Paris in twenty to twenty-two, Bruges in twenty-five and Seville, a journey of two thousand kilometres, in thirty-two days. The annotations on the letters exchanged between Andrea Barbarigo in Venice and correspondents in Bruges, London

and Valencia suggest this timetable could generally be adhered to: only the Seville itinerary seems unfairly demanding.

10

The most sustained evidence for the efficiency of the courier service around the year 1400 comes from the Datini archive. An examination of his correspondence, together with notes of arrival and despatch of letters in the account books, produces evidence of around 320,000 dated epistolary transactions. The seventeen thousand letters between Florence and Genoa and the seven thousand letters between Florence and Venice took between five and seven days to arrive. Delivery times to London were more variable, depending as they did on the vagaries of the Channel crossing. On the other hand the post between Venice and Constantinople was remarkably reliable: letters would arrive between thirty-four and forty-six days of despatch.

11

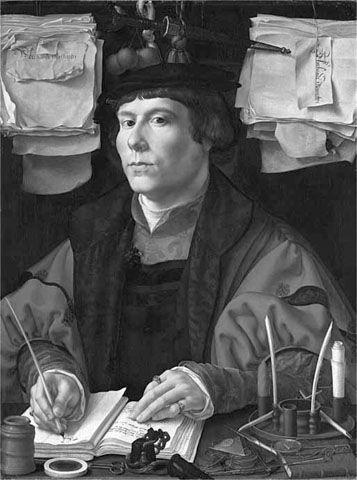

2.1 The birth of a paper culture. Merchants and other writing professionals were forced to develop systems for filing incoming documents and correspondence.