The Irish Revolution, 1916-1923 (4 page)

Read The Irish Revolution, 1916-1923 Online

Authors: Marie Coleman

Tags: #History, #General, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #Ireland, #Great Britain

Lord Lieutenant

: The King's representative in Ireland under the Act of Union.

Northern Ireland

: Six-county home rule entity created by the Government of Ireland Act (1920) comprising Counties Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone.

Proportional representation by single transferable vote (PRSTV)

: An electoral system based on multiple-seat constituencies, in which voters vote numerically in order of preference (1, 2, 3 . . . ), and votes are allocated accordingly until all seats are filled. Favours smaller parties.

Representation of the People Act (1918)

: Legislation extending the vote to women over 30 and widening the franchise generally.

Revisionism

: A term used to describe a critical re-evaluation of history that emerged in Ireland from the 1930s. In the context of the Irish revolution it is often a pejorative term applied to historians seen as critical of the traditional nationalist interpretation of the period.

Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)

: The police force for Ireland outside of Dublin, which was disbanded in 1922.

Sinn Féin

: Political party formed by Arthur Griffith in 1905, adopted a republican constitution in 1917 and split in January 1922 into pro-treaty (later Cumann na nGaedheal) and anti-treaty factions and again in 1926 with the formation of Fianna Fáil.

Solemn League and Covenant

: Commitment to resist home rule signed by over 200,000 men in Ulster in September 1912. A corresponding declaration was signed by over 200,000 women.

Squad

: A death squad controlled by Michael Collins that targeted British Intelligence agents and was responsible for high-profile killings such as Bloody Sunday.

Teachta Dála (TD)

: Member of Dáil éireann.

Third home rule bill

: Irish home rule bill introduced in April 1912 and passed in September 1914 but suspended for the duration of the war and subsequently abandoned and replaced by the Government of Ireland Act in 1920.

Ulster Provisional Government

: Plans for a breakaway government drawn up by the Ulster Unionists in the event of home rule being imposed against their will in 1914.

Ulster Special Constabulary (USC)

: Special constabulary formed to deal with violence in Ulster in 1920 that contained a large number of Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) members and was associated with high-profile sectarian attacks and killings of Catholics.

Ulster Unionist Party

: The political party representing unionists in Ulster.

Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

: A paramilitary force formed in Ulster in January 1913 to resist home rule by force, many of whose members were killed in the First World War.

Plates

The following plates appear between pages 95 and 96.

1 John Redmond delivering a speech on the third home rule bill, April 1912

2 The destruction of the GPO after the Easter Rising, 1916

3 The Irish Citizen Army outside Liberty Hall

4 Arthur Griffith (1871–1922)

5 Eamon de Valera (1882–1975)

6 Constance Markievicz (1868–1927)

7 Anti-conscription pledge poster

8 Auxiliary recruits

9 The Irish Army taking over Portobello Barracks, Dublin, in 1922

10 Sir James Craig, first prime minister of Northern Ireland at the opening of the Northern Ireland Parliament in City Hall, Belfast, June 1922

1 Map of central Dublin showing the principal locations of action during the Easter Rising.

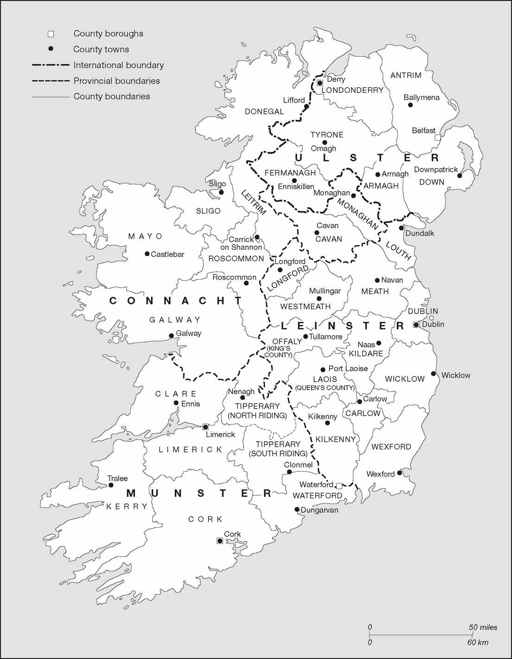

2 Map of Ireland showing county boundaries and the border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State.

Bartlett, T. (2010)

Ireland: A History

. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boyce, D. G. (1992)

Ireland 1828–1923: From Ascendancy to Democracy

. Oxford: Blackwell.

Boyce, D. G. (1995)

Nationalism in Ireland

, 3rd edition. London: Routledge.

Boyce, D. G. (1996)

The Irish Question and British Politics, 1868–1996

. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Boyce, D. George (ed.) (1988)

The Revolution in Ireland, 1879–1923

. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

English, R. (2003)

Armed Struggle: A History of the IRA

. London: Macmillan.

English, R. (2007)

Irish Freedom: A History of Nationalism in Ireland

. London: Macmillan.

Fitzpatrick, D. (1998)

The Two Irelands, 1912–1939

. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jackson, A. (1999)

Ireland, 1798–1998

. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lyons, F. S. L. (1971)

Ireland Since the Famine

. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Smith, J. (1999)

Britain and Ireland: From Home Rule to Independence

. Harlow: Longman.

Townshend, C. (2013)

The Republic: The Fight for Irish Independence, 1918–1923

. London: Allen Lane.

Vaughan, W. E. (ed.) (1996)

A New History of Ireland, Vol. VI: Ireland Under the Union II, 1870–1921

. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Walsh, O. (2002)

Ireland's Independence, 1880–1923

. London: Routledge.

1 The Irish Question, 1870–1916

I

n the last quarter of the nineteenth century a vigorous political movement emerged in Ireland seeking home rule, a form of devolved government that would give Ireland control of its own affairs while remaining within the imperial framework. Ireland would remain part of the United Kingdom with Great Britain that was formed in 1801 but the Westminster Parliament would not have sole legislative jurisdiction for Ireland.

Home rule

was the latest manifestation of a nineteenth-century tradition of using constitutional means to achieve some modification of the

Act of Union

and was preceded by O’Connell’s emancipation and repeal movements in the 1820s and 1840s, and the Independent Irish Party in the 1850s.

Home rule

: Devolved government for Ireland within the United Kingdom. Existed in Northern Ireland 1921–72.

A second impetus for the emergence of the home rule movement was the campaign for an amnesty for Fenian prisoners. The

Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB)

, popularly known as the Fenians, was a secret revolutionary organisation. Following an abortive uprising in 1867 many of its members were imprisoned and an Amnesty Association was formed, comprising Fenian sympathisers and constitutional nationalist politicians, to seek a reprieve for them. The president of the association was a Protestant lawyer from Donegal, Isaac Butt, who had defended Fenian prisoners. Initially a Tory who opposed repeal of the union, the experience of the famine in the 1840s and of defending nationalists gradually brought him around to supporting a measure of Irish self-government.

Act of Union

: Political, economic and religious union of Ireland with Great Britain from 1801 until 1921.

Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB)

: Secret oathbound society formed in 1858 to achieve an Irish republic by revolutionary means. Responsible for planning the Easter Rising.

In 1870 Butt formed the Home Government Association, which was essentially a Dublin-based pressure group, initially composed mostly of Protestants. It had a very limited appeal and did not enjoy much success (O’Day, 1998: 29). A broader-based Home Rule League was formed in 1874, enjoying immediate success with the return of 59 home rule candidates in that year’s general election. The parliamentary strength of the league was somewhat illusory as many of those elected were former Liberals who had

simply switched over to the increasingly popular new political movement. In reality, only about one-third of those elected in 1874 were committed home rulers, and many abandoned their short-lived dalliance with home rule as soon as election had been secured (Thornley, 1964: 195–6).

The Fenian uprising also had a significant impact on British politics. The Liberal Party leader, William Gladstone, who became Prime Minister in 1868, saw the rebellion as an indication that reform was badly needed in Ireland to assuage the discontent that had precipitated it. For the next 25 years Ireland became a ‘preoccupation’ for Gladstone. The policy he adopted towards Ireland was aimed at drawing a line ‘between the

Fenians

and the people of Ireland and to make the people of Ireland indisposed to cross it’. In pursuit of this policy he sought to introduce a level of reform that would detract support from revolutionary nationalism while preserving Ireland’s place within the union. His first government sought ‘justice for Ireland’ through disestablishment of the Church of Ireland, land reform and solving the issue of university education for Catholics, but was still a long way from supporting home rule (Matthew, 1986: 192–6).

Fenians

: See

Irish Republican Brotherhood

.

The first Irish Home Rule Party made very little impression at Westminster between 1874 and 1877. The first home rule resolution introduced by Butt in July 1874 was defeated soundly by 458 votes to 61 and his land reform bill met a similar fate in 1876. In 1877 a group of Irish Members of Parliament (MPs), including Joseph Biggar and Charles Stewart Parnell, resorted to the tactic of obstruction, essentially filibustering and delaying the workings of Parliament with long speeches and frequently tabling amendments to legislation. The stratagem which was opposed by Butt divided the party and by the time of his death in May 1879 it had little to show for five years in parliament (Thornley, 1964: 233, 274, 335).

Butt’s failure was partly due to his own personality, which was unsuited to political life, and his precarious personal finances, which required him to spend much of his time on the legal circuit in Ireland to the neglect of his leadership of the parliamentary party. The perceived Protestant dominance of the early home rule movement made essential allies such as the Roman Catholic clergy, tenant farmers and the remnants of the Fenians suspicious of it. Even if Butt had garnered greater support in Ireland and been a more effective party leader, it would have been to little avail as there was no significant support in Britain for Irish home rule, which was an essential prerequisite for its success. Nevertheless, Butt bequeathed an important legacy to his successors; a distinct

Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP)

existed at Westminster and home rule had been established as the minimum demand of Irish nationalists (Thornley, 1964: 380–7).

Irish Parliamentary Party (Irish Party/IPP)

: The Irish home rule party.

By the late 1870s home rule had also been over-shadowed by the emergence of the Land War. An economic depression in the late 1870s,

caused by unusually bad weather and a succession of bad harvests, resulted in a decline in both crop and livestock production. An influx of cheap grain from the USA, the curtailment of credit and the refusal of landlords to lower rents resulted in an increase in evictions and a generally precarious situation for Irish tenant farmers. In 1879 the Land League was formed in County Mayo, initially to protect tenants during the immediate crisis, but with the long-term aim of replacing landlords. As the rising star of Irish nationalist politics, Parnell accepted the presidency of the League and much of the period from 1879 to 1882 was taken up with the land issue.