The Italian Boy (17 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

Thomas, along with Constable Higgins, laborer and gardener James Waddy, James Corder, William Cribb (the coroner’s jury foreman, with no obvious official interest in the case), and a number of Division F officers went to the deserted cottage at noon on Saturday, 19 November. Thomas was very interested in that long back garden. He noticed that a pathway running its entire length, from the house to the privy, looked uneven, and in places the soil appeared to be loose; there was indeed a thin layer of ashes on the surface at one spot. Bishop’s eldest son stood by during the digging, and it is possible that Thomas had asked for him to be present in the hope that the lad might let slip something incriminating. Indeed, as Higgins started to prod the earth near the path with an iron bar, the boy told him to take care, since there was a cesspool lying immediately beneath. This warning made Thomas suspicious, and he told Higgins to explore exactly that spot. Here, five yards from the Bishops’ back door and one yard from the palings, Higgins’s bar came up against a spongy substance. Waddy dug and, about a foot down, unearthed a child’s jacket, trousers, and shirt. The jacket was of good-quality blue cloth with two rows of covered buttons and expertly sewn buttonholes; some gilt buttons also on the jacket had a star motif at their center. The black trousers looked as though they had been removed with force, since the buttonholes that connected them to their yellow calico braces were torn. A yard away, Waddy and Higgins dug up another set of clothes—a shabby blue coat of an unusual cut (later described in court as being like the sort worn by charity-school boys) with white buttons, a pair of coarse gray trousers with patched knees, an old shirt that was ripped down the middle, and a striped waistcoat that had bloodstains on the collar and shoulder and, in its pocket, a small piece of comb. The waistcoat had once been an adult’s but had been cut down and restitched to fit a boy. Thomas noted that this had been done in a slipshod way, using cheap, coarse yarn. When the waistcoat was shown to Minshull, the magistrate pointed out that it could prove significant, since it might bring forward the man to whom it had originally belonged.

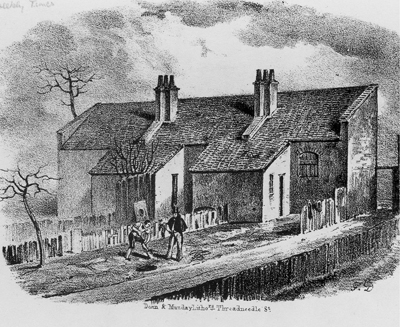

Police officers begin their search of Nova Scotia Gardens, in this curiously compressed version of Bishop’s and Williams’s cottages.

In the privy at the bottom of the garden of Number 3 Thomas found a human scalp with long matted brown hair attached; down among the feces, the officers worked to disentangle chunks of human flesh. Thomas and his men—and, later, the magistrates—assumed that this find was evidence of Bishop and Williams’s resurrection work; there was a good trade in body parts if the entire corpse was not fresh, and the scalp had probably been removed for the sale of the hair to a wigmaker and discarded once it was known that the house might be searched.

At four o’clock in the afternoon, with the garden dug to a depth of one foot and the privy thoroughly probed, the men went home. Two days later, Thomas returned and searched the inside of the house once more. The downstairs room (the parlor) contained scarcely any furniture—there was a fireplace and the remains of a small, rickety cupboard. In one corner lay a heap of old, soiled clothes, many of them children’s. Sarah Bishop worked as a washerwoman, taking in washing for locals; but the womenfolk of resurrectionists were known to make money from selling the clothing from pauper bodies stolen from mortuaries, hospitals, or workhouses. Superintendent Thomas was particularly interested in a woman’s bonnet and a brown, furry cap—the color of dark fox fur—that was lying near the top of the heap; on his first visit to the cottage he had seen it hanging on a nail in the parlor and had taken little notice of it. But now it intrigued him. He took it to show Margaret King and her family in Crabtree Row, and then to Covent Garden to see what Joseph Paragalli made of it. The Italian told Thomas that Carlo Ferrari had worn a cap very like it when he first came to London; he added that Carlo’s cap had been larger but that this one looked as though it had been taken in. The fur crown of the cap was English, Paragalli said, but its green visor had been made in France.

Thomas seems to have found it hard to keep away from Nova Scotia Gardens. No. 3 was now officially in police hands, and the superintendent continued to scour it for anything that would forge links in the story he was piecing together. He had told Minshull that he found the Gardens “remarkable,” that there was not a street lamp within a quarter of a mile of the place, and that he considered No. 3 itself to be “in a ruinous condition,” its garden little more than waste ground.

7

Thomas pointed out to Minshull that Bishop and Williams had access to around thirty other gardens, since they had only to step over the palings to reach the privies and grounds of their neighbors. Searching these would not be a problem, he said, since people were moving out swiftly, in horror and shame at the new notoriety of the Gardens. Minshull was pleased with the trophies the superintendent was bringing into his office and was agog at the news of his daily progress.

On Tuesday, 22 November, Thomas decided to take a look at 2 Nova Scotia Gardens. It had lain empty after Williams went to live with the Bishops in the last week of September until William Woodcock, a brass worker, his wife, Hannah, and their twelve-year-old son, also called William, moved in on 17 October. Superintendent Thomas found nothing of significance in the house, but from the bottom of Woodcock’s privy he retrieved a bundle: unwrapped, it contained a woman’s black cloak that fastened to one side with black ribbon, a plaid dress that had been patched in places with printed cotton, a chemise, an old, ragged flannel petticoat, a pair of stays that had been patched with striped “jean” (a heavy, twilled cotton), and a pair of black worsted stockings, all of which appeared to have been violently torn or cut from their wearer. There was also a muslin handkerchief, a red pincushion, a blue “pocket” (a poor woman’s equivalent of a purse or small everyday bag), and a pair of women’s black, high-heeled, twilled-silk shoes. The dress and chemise had been ripped up the front, as had the petticoat, which also had two large patches of blood on it. The stays had been cut off in a zigzag manner.

Thomas decided to search the well in Bishop’s garden; it was covered over by planks of wood, onto which someone had scattered a pile of grass cuttings. From the bottom of the well he fished out a bundle that proved to be a shawl wrapped around a large stone.

During Thomas’s inquiries at the anatomical schools of London he had been told by Guy’s Hospital that two bodies—one of them a young female—had been bought from Bishop in the first week of November; St. Bartholomew’s had told him that Bishop had offered them a boy and a woman within the month before his arrest; and George Pilcher and John Appleton—respectively, anatomy lecturer and porter at Grainger’s school in Webb Street—had told him that a tall, thin, middle-aged woman had been sold to Pilcher by Bishop early in October. Several women had lately been reported missing in Bethnal Green and Shoreditch; two sets of worried relatives had already contacted Thomas. A number of local children had not been seen for months. It was dawning on the superintendent that what had been going on at Nova Scotia Gardens was not the processing of disinterred corpses into saleable Subjects but systematic slaughter.

SIX

Houseless Wretches Again

Urban poverty, so often a disgusting and harrowing sight to the respectable, could also be a source of wonder and intrigue. A beggar with a certain look or air or “act” could feed on city dwellers’ craving for novelty and display. Certain street people, moving around wealthy West End districts as well as the poorer locales, began to take on the status of peripatetic performers, with the slightly unreal aura of renowned theatrical or operatic artistes, standing out amid the rush and bustle, seeping into urban popular consciousness. Rarely mentioned in the newspaper columns or police reports of the day, they survived in the reminiscences of those who thought to note them down before their image faded forever. They were described as though they were apparitions, and they seem to haunt, rather than inhabit, the city, their connections to their environment mysterious and unfathomable.

One such phantasmagoric creature was Samuel Horsey, who trundled around in a wooden cart–cum–sledge. His story was that the celebrated surgeon John Abernethy had removed both his legs at St. Bartholomew’s; some thought the amputations had been the result of a war injury, others that they followed his participation in London’s anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of 1780. He frequently frightened horses by rolling into their eyeline, then berating them loudly when they whinnied or reared in terror; and he would erupt into pubs and gin shops by bashing his cart at the doors until they burst open to let him in. Black Joe Johnson was a West Indian who wore a model of Nelson’s ship

Victory

built onto his hat and would come up to ground-floor windows and move his head so that the ship appeared to be sailing along the sill as he sang a sea shanty. The Dancing Doll Man of Lucca played drum and flute as puppets danced on a board in front of him, worked by strings attached to his knee (in fact, there appear to have been at least ten Dancing Doll Men of Lucca in London at the same time). Possibly in imitation of such continental élan, blind Charles Wood exhibited a poodle, the Real, Learned, French Dog, Bob, who wore a frock coat and danced to the organ played by Wood (“Look about Bob, be sharp, see what you’re about”).

1

Tim Buc Too was an old African street-crossing sweeper, whose spot was at Ludgate Hill/Fleet Street; he arranged his profuse white hair so it looked as though he were wearing a pith helmet. In Camden Town, “TL,” a fifty-four-year-old former servant unable to find work, exhibited in the street his own scale model of Brunel’s Thames Tunnel—the “Great Bore” that was taking years longer than anticipated to complete.

2

Samuel Horsey was one of London’s most famous sledge beggars.

There was a sense that these people were unlikely to survive much longer in the type of city that London was becoming and in the kind of society that was coming into being. Journalist Charles Knight expressed concern that the street sights were being “shouldered out by commerce and luxury.”

3

Writing in 1841, seventeen years after the passage of the Vagrancy Act and twelve years after the arrival of the Metropolitan Police, Knight regretted that girls carrying pails of milk, fresh herbs, and watercress from the country were less often to be seen selling their goods in the streets. It was, Knight wrote, a quieter, duller London, now that the muffin man could not scream out his wares, no bugle could be sounded to announce news and events, and “chaunters” were not permitted to sing the first few lines of a broadsheet to tempt a passerby. The itinerant traders were being driven off as much by competition from fixed-location shopkeepers as by legal prohibitions on noise and nuisance; the introduction of plateglass and gas lighting and the proliferation of cheaper, more diverse, and increasingly exotic goods in shops and bazaars were rendering the peddler obsolete.

Artistic attempts were made to capture some of the grotesque individuals who wandered the town, those who were felt to be under threat of extinction by “progress.” J. T. Smith, keeper of the prints at the British Museum, compiled

Etchings of Remarkable Beggars

in 1815 and

Vagabondiana

in 1817—both compendia of destitute people. Smith’s later work,

The Cries of London

, recorded the chants and ditties of dead, or soon-to-be-dead, trades. His sketches included Anatony Antonini, who carried a huge tray of silk and paper flowers (“All in full bloom!”) with plaster birds attached to them; William Conway, an itinerant spoon seller of Crabtree Row, Bethnal Green (“Hard-metal spoons to sell or mend”), who once rescued Smith when he was surrounded and threatened by a crowd while sketching another beggar (the locals had thought Smith was an authority figure, sent to snoop on them); George Smith, a rheumatic brush maker, reduced to peddling groundsel and chickweed; and Jeremiah Davies, a Welsh weight-lifting dwarf, who performed his tricks around Chancery Lane. Eking a living from the bizarrest of trades—that was typical of the city, where people subsisted on a seemingly infinite subdivision of labor, associated trades spun out of associated trades.