The Italian Renaissance (17 page)

Read The Italian Renaissance Online

Authors: Peter Burke

The third prejudice against the visual arts was that artists were ‘ignorant’ – in other words, they lacked a certain kind of training (in theology and the classics, for example) that had a higher esteem than the training which they had received and their critics had not. When cardinal Soderini was trying to excuse Michelangelo’s flight from Rome (below, p. 114), he told the pope that the artist ‘has erred through ignorance. Painters are all like this both in their art and out of it.’ It is a pleasure to record that Julius did not share this prejudice. He told Soderini roundly: ‘You’re the ignorant one, not him!’

105

Although a few artists, already mentioned, became rich by means of their art, many remained poor. Their poverty was probably as much the cause as the result of prejudices against the arts. The Sienese painter Benvenuto di Giovanni declared in 1488 that ‘The gains in our profession are slight and limited, because little is produced and less earned.’

106

Vasari made a similar point: ‘The artist today struggles to ward off famine rather than to win fame, and this crushes and buries his talent and obscures his name.’ Vasari’s comment might be dismissed as special pleading, inconsistent with what he says elsewhere (let alone with his own wealth). Benvenuto’s remarks, on the other hand, come from his tax return, which he knew would be subject to checking. The same goes for

Verrocchio, whose return for 1457 claims that he was not earning enough to keep his firm in hose (

non guadagniamo le chalze

).

107

Botticelli and Neroccio de’Landi went into debt. Lotto was once reduced to trying to raffle thirty pictures, and he was able to dispose of only seven of them.

Humanists too did not always make fortunes and they were not invariably respected. The Greek scholar Janos Argyropoulos is said to have been so poor at one time that he was forced to sell his books. Bartolommeo Fazio had an up-and-down career, at one time a schoolteacher in Venice and Genoa, at another a notary in Lucca, before he landed a safe and well-paid job as secretary to Alfonso of Aragon. Bartolommeo Platina worked in a variety of occupations – soldier, private tutor, press-corrector, secretary – before becoming Vatican librarian. Angelo Decembrio was at one time a schoolmaster in Milan, Pomponio Leto in Venice and Francesco Filelfo in several different towns. Jacopo Aconcio was at one time a notary, at another secretary to the governor of Milan, at another trying his luck in England.

These humanists were the distinguished ones. To calculate the status of the group as a whole, it is also necessary to consider the less important ones. Ideally, if the evidence permits, a study should be made of the careers of all the students of the humanities. Until such a study is published, it is difficult to do more than guess at the status of humanists. My own guess would be that there was a considerable gap between the few stars and the less successful majority, even if a small-town teacher or impoverished corrector for the press might enjoy a status higher than that of a successful but ‘ignorant’ artist. Musicians, whose low status was lamented by Alberti, seem to have been in a similar position. For every lutenist who was rewarded by a patron as generous as Pope Leo X, there must have been many who were poor, since there were few Italian courts and still fewer honourable positions outside them.

In summing up, it is tempting to take the easy way out and to close on a note of ‘on the one hand … on the other’. However, it is possible to make a few more precise points – three at least. As in the case of training, so in status the creative elite formed two cultures, with literature, humanism and science enjoying more respect than the visual arts and music. All the same, to choose the humanities as a career was to take a considerable risk. Many were trained but few were chosen. In the second place, Renaissance artists were an example of what sociologists call ‘status dissonance’. Some of them achieved high status, others did not. According to some criteria, artists deserved honour; according to others, they were just craftsmen.

Artists were in fact respected by some of the noble and powerful, but they

were despised by others. The status insecurity which naturally resulted may well explain the touchiness of certain individuals, such as Michelangelo and Cellini. In the third place, the status of both artists and writers was probably higher in Italy than elsewhere in Europe, higher in Florence than in other parts of Italy, and higher in the sixteenth century than it had been in the fifteenth. They might be represented as melancholy geniuses (plate 3.8).

108

By the middle of the sixteenth century it was no longer extraordinary for artists to have some knowledge of the humanities; the distinction between the two cultures was breaking down.

109

The social mobility of painters and sculptors is symbolized if not confirmed by the appearance of the term ‘artist’ in more or less its modern meaning.

If the artist was not an ordinary craftsman, what was he? He could if he wished imitate the style of life of a nobleman, a model suitable for those endowed with wealth, self-confidence and the ability to behave like something out of Castiglione’s

Courtier

. A number of artists, mainly sixteenth-century ones, are described in these terms in Vasari’s

Lives

. An obvious example is Raphael, who was in fact one of Castiglione’s friends. Other instances of the artist as gentleman are Giorgione, Titian, Vasari’s kinsman Signorelli, Filippino Lippi (described as ‘affable, courteous and a gentleman’), the sculptor Gian Cristoforo Romano (who makes an appearance in

The Courtier

), and a small number of others, including, of course, Vasari himself. All the same, the artist who adopted this role still had to face the social prejudice against manual labour which has just been described. For those who were no longer content to be ordinary craftsmen, yet lacked the education and poise necessary to pass as gentlemen, a third model was developed in this period (how self-consciously, it is hard to say) – that of the eccentric or social deviant.

At this point distinctions are necessary. Vasari and others have recorded a number of highly dramatic stories about artists of the period who killed or wounded men in brawls (Cellini, Leone Leoni and Francesco ‘Torbido’ of Venice) or committed suicide (Rosso, Torrigiani). Others were described by contemporaries as ‘sodomites’ (Leonardo, ‘Sodoma’). The significance of these stories is difficult to assess. The evidence is insufficient to determine whether these artists were what they were described as being, and, even if they were, we cannot conclude from a few cases that artists were more likely than other social

groups to kill others or themselves or to love members of the same sex.

110

There is a much richer vein of contemporary comment about a more significant kind of eccentricity associated with artists: irregular working habits. In one of the stories of Matteo Bandello, who was in a good position to know, there is a vivid description of Leonardo’s way of working, which stresses his ‘caprice’ (

capriccio

,

ghiribizzo

).

111

Vasari made similar comments about Leonardo, and told a story in which the artist justified his long pauses to the duke of Milan with the argument that ‘Men of genius sometimes accomplish most when they work the least; for they are thinking of designs’ (

inventioni

). The key concept here is a relatively new one, ‘genius’ (

genio

), which turned the eccentricity of artists from a liability into an asset.

112

Patrons had to learn to put up with it. On one occasion the marquis of Mantua, explaining to the duchess of Milan why Mantegna had not produced a particular work on time, made the resigned remark that ‘usually these painters have a touch of the fantastic’ (

hanno del fantasticho

).

113

Other clients were less tolerant. Vasari remarked of the painter Jacopo Pontormo that ‘What most annoyed other men about him was that he would not work save when and for whom he pleased and after his own fancy.’ Composers – or their patrons – posed similar problems. When the duke of Ferrara wanted to hire a musician, he sent one of his agents to see – and hear – both Heinrich Isaac and Josquin des Près. The agent reported that ‘It is true that Josquin composes better, but he does it when he feels like it, not when he is asked.’ It was Isaac who was hired (below, p. 120).

114

In the case of other artists, their eccentricity took the form of doing too much work rather than too little, and neglecting everything but their art. Vasari has a series of such stories. Masaccio, for example, was absent-minded (

persona astratissima

): ‘Having fixed his mind and will wholly on matters of art, he cared little about himself and still less about others … he would never under any circumstances give a thought to the cares and concerns of this world, nor even to his clothes, and was not in the habit of recovering his money from debtors.’ Again, Paolo Uccello was so fascinated by his ‘sweet’ perspective that ‘He remained secluded in his house, almost like a hermit, for weeks and months, without

knowing much of what was going on in the world and without showing himself.’

115

Vasari also gives a vivid account of the ‘strangeness’ of Piero di Cosimo, who was absent-minded, loved solitude, would not have his room swept, and could not bear children crying, men coughing, bells ringing or friars chanting (is his attempt to preserve himself from distraction really so ‘strange’?).

The fact that Masaccio, in early fifteenth-century Florence, is presented as uninterested in money is a trait worth emphasis. A still more conspicuous contempt for wealth is shown by Donatello, of whom ‘It is said by those who knew him that he kept all his money in a basket, suspended from the ceiling of his workshop, so that everyone could take what he wanted whenever he wanted.’

116

This looks very much like a conscious rejection of the fundamental values of Florentine society. Why Donatello should have rejected these values emerges from another story of Vasari’s, about a bust made by the sculptor for a Genoese merchant, who claimed to have been overcharged because the price worked out at more than half a florin for a day’s work.

Donatello considered himself grossly insulted by this remark, turned on the merchant in a rage, and told him that he was the kind of man who could ruin the fruits of a year’s toil in the hundredth part of an hour; and with that he suddenly threw the bust down into the street where it shattered into pieces, and added that the merchant had shown he was more used to bargaining for beans than for bronzes.

Whether the point was Donatello’s or Vasari’s, the moral is clear: works of art are not ordinary commodities, and artists are not ordinary craftsmen to be paid by the day.

One is reminded of what the attorney-general said to Whistler about his

Nocturne

, and the artist’s reply: ‘The labour of two days then is that for which you ask 200 guineas?’ ‘No: I ask it for the knowledge of a lifetime.’ The point still needed to be made in 1878. However, the question was very much alive in Renaissance Italy. The archbishop of Florence recognized, as we have seen (p. 81), that artists claimed with some justification to be different from ordinary craftsmen. Francisco de Hollanda, a Portuguese in the circle of Michelangelo, argued still more forcefully that ‘Works of art are not to be judged by the amount of useless labour spent

on them but by the worth of the knowledge and skill which went into them’ (

lo merecimento do saber e da mao que as faz

).

117

P

LATE

3.8 P

ALMA

V

ECCHIO

:

P

ORTRAIT OF A

P

OET

The same idea, that the artist is not an ordinary craftsman, may well

underlie the behaviour of Pontormo (again according to Vasari) when he rejected a good commission and then did something ‘for a miserable price’. He was showing the client that he was a free man. Artistic eccentricity carried a social message.

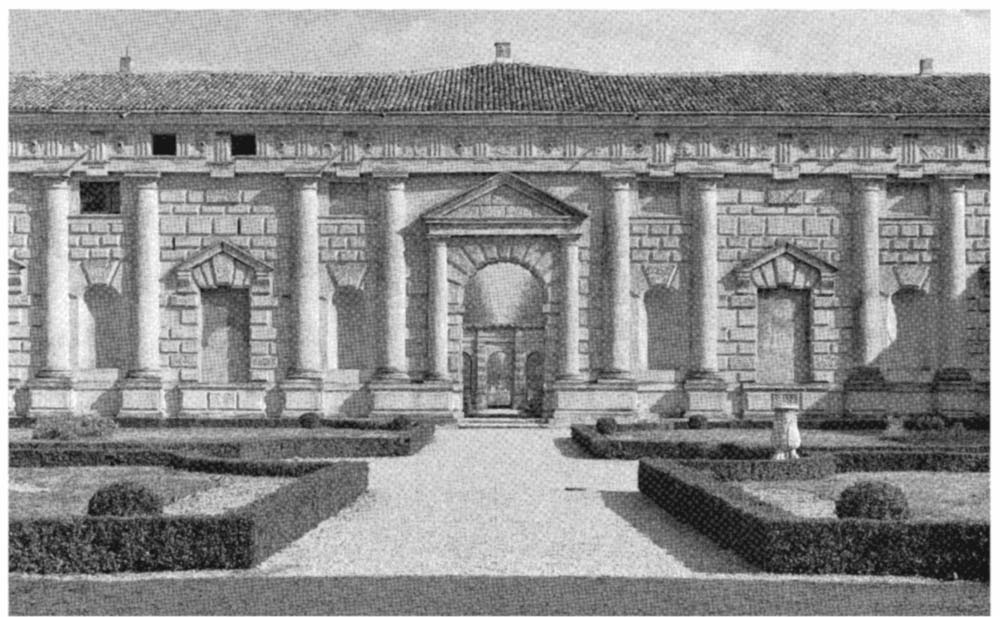

P

LATE

3.9 G

IULIO

R

OMANO

: T

HE

P

ALAZZO

DEL

T

E

, M

ANTUA

,

DETAIL OF A FRIEZE WITH SLIPPED TRIGLYPHS