The Italian Renaissance (20 page)

Read The Italian Renaissance Online

Authors: Peter Burke

Another kind of corporate patron was the state, whether republic or principality. It was the Signoria, the government of Florence, which commissioned Leonardo’s

Battle of Anghiari

and its companion piece, Michelangelo’s

Battle of Cascina

. In Venice there existed an official position of Protho, or architect to the Republic (held by Jacopo Sansovino, among others), and a quasi-official position of painter to the Republic (offered to Dürer on one occasion and held by both Giovanni Bellini and Titian).

9

However, one painter alone could not cope with all the state’s commissions. In 1495 there were nine painters, including Giovanni Bellini and Alvise Vivarini, working on battle scenes to decorate the Hall of the Great Council in the Doge’s Palace. The problems of patronage by committee emerge clearly from the documents referring to a battle scene by Titian for the same place. In 1513 Titian petitioned the Council of Ten to be allowed to paint it, with the help of two assistants. A resolution accepting the offer was carried (10 votes to 6); Bellini protested. In March 1514 the decree was revoked (14 votes to 1) and the assistants were struck off the payroll; Titian protested. In November, the revocation was revoked (9 votes to 4), and the assistants reappeared on the payroll. Then it was reported that three times as much money had been spent as need have been, and all arrangements were cancelled. Titian agreed to accept a single assistant, and his offer was accepted in 1516, but the battle painting was still unfinished in 1537.

10

Individual patrons came from a wide range of social groups, not just the social and political elites. Architecture and sculpture were usually expensive, but the evidence of wills shows that some shopkeepers and artisans commissioned chapels.

11

There is also evidence that some people with modest incomes commissioned paintings. The surviving documents are concerned mainly with upper-class patronage, but those are the precisely the documents that are most likely to survive. In any case there are records of some commissions by merchants, shopkeepers, artisans and even peasants.

Take the case of portraits. Portraits of merchants were not uncommon. Among those that have survived are Leandro Bassano’s

Orazio Lago

and

Giovanni Battista Moroni’s

Paolo Vidoni Cedrelli

. Lorenzo Lotto noted in his account-book the names of five businessmen he painted – ‘a merchant from Ragusa’, ‘a merchant from Lucca’, ‘a wine merchant’, and so on. Lotto also painted a surgeon from Treviso (at this time the status of surgeons, who were associated with barbers, was rather low) and a portrait of ‘Master Ercole the shoemaker’, who paid him in kind rather than in cash.

12

Hence Moroni’s famous portrait of a tailor, still to be seen in the National Gallery in London, is likely to be a portrait rather than, as was once thought, a genre painting.

Again, take the case of religious paintings. There are casual references in Vasari to artisan clients, such as the mercer and the joiner who commissioned Madonnas from Andrea del Sarto and the tailor who commissioned Pontormo’s first recorded work. Again, the will of an agricultural labourer who lived near Perugia leaves 10 lire to pay for a painting of Christ in majesty (a

Maestà

) to hang above his grave.

13

Ex-votos (discussed below, p. 136) were also commissioned by ordinary people. What we do not know is whether popular patronage of art was as commonplace as it would be in the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth century.

Recent research, as we have seen (above, pp. 9–10) has revealed that female patrons were an important group. Scholars now go far beyond the unusually well-documented case of Isabella d’Este (Plate 4.4).

14

They distinguish the patronage of nuns, the Dominicans for instance, and of laywomen, that of wives and that of widows (widows had more freedom to do as they liked). A few noblewomen built palaces, such as Ippolita Pallavicino-Sanseverina at Piacenza.

15

Some women, such as Margarita Pellegrini of Verona, were able to commission a chapel, while Giovanna de’Piacenza commissioned Correggio’s now famous frescoes in the Camera di San Paolo, a room in a convent in Parma. Others, such as the widow Lucretia Andreotti of Rome, commissioned a tomb. Yet others commissioned altarpieces, which might include their portrait as the donor, as in the case of a panel by Carlo Crivelli that has a tiny figure of the donor, Oradea Becchetti of Fabriano, kneeling at the feet of St Francis.

16

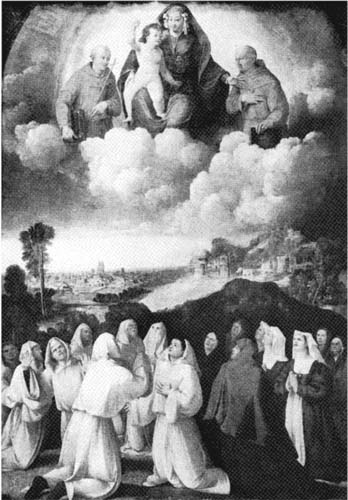

P

LATE

4.2 B

ATTISTA

D

OSSI

:

M

ADONNA

WITH

S

AINTS AND THE

C

ONFRATERNITY

P

LATE

4.3 A

NDREA DEL

C

ASTAGNO

:

T

HE

Y

OUTHFUL

D

AVID

,

TEMPERA ON LEATHER MOUNTED ON WOOD,

C

.1450

How did artists acquire patrons or clients, or patrons acquire artists? When artists heard that projects were in the air, they might approach the patron directly or through an intermediary. For example, in 1438 the painter Domenico Veneziano wrote to Piero de’Medici: ‘I have heard that Cosimo [Piero’s father] has decided to have an altarpiece painted, and wants a magnificent work. This pleases me a great deal, and it would please me still more if it were possible for me to paint it, through your mediation’ (

per vostra megianita

).

17

In 1474, there was news in Milan that the duke wanted a chapel painted at Pavia. The duke’s agent complained that ‘all the painters of Milan, good and bad, asked to paint it, and trouble me greatly about it.’ Again, in 1488, Alvise Vivarini petitioned the doge to let him paint something for the Hall of the Great Council in Venice as the Bellinis were doing, and in 1515, as we have seen, Titian made a similar request.

18

In these cases, as in many other matters, friendships, equal and unequal, counted for a great deal. Art patronage was part of a much larger patron–client system, discussed in

chapter 9

. The importance of friends and relations may be illustrated from the careers of two sixteenth-century Tuscan artists, Giorgio Vasari and Baccio Bandinelli. Vasari came to work for Ippolito and Alessandro de’Medici because he was a distant relative of their guardian, Cardinal Silvio Passerini. After his hopes had been ‘blown away’, as we have seen, by the death of Duke Alessandro, Vasari managed to enter the permanent service of his successor Cosimo. Bandinelli also had a family connection with the Medici in the sense that his father had worked for them before their expulsion from Florence in 1494. After their restoration in 1513, Baccio introduced himself to the brothers Giovanni (soon to become Pope Leo X; Plate 4.7) and Giuliano, offered them a gift, and received commissions in return. Bandinelli also worked for Giulio de’Medici, who became Pope Clement VII. He expected the commission to make the tombs of both Medici popes and visited Cardinal Salviati so often to arrange this that, as Vasari tells us in his biography of Bandinelli, he was mistaken for a spy and nearly assassinated.

It is less easy to discover how patrons chose particular artists. The less expert sometimes asked advice of others, such as Cosimo de’Medici (as we have seen) or his grandson Lorenzo the Magnificent. It was Lorenzo,

for example, who recommended the sculptor Giuliano da Maiano to prince Alfonso of Calabria. Princes might commission artists via intermediaries, such as court officials, as in Milan under the Sforza.

19

Some patrons seem to have chosen between rival offers on financial grounds, others for stylistic reasons. The duke of Milan’s agent, in the case of the chapel quoted above, chose the artists who offered to do the work for 150 rather than for 200 ducats. Twenty years later, however, a memorandum from the papers of the new duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, attempted to distinguish between Botticelli, Filippino Lippi, Perugino and Ghirlandaio on the grounds of style (cf. p. 152 below).

20

Formal competitions for commissions also took place on occasion, especially in Florence and Venice, which is what one might have expected from republics of merchants. The most famous of these competitions are surely those for the Baptistery doors in Florence in 1400 (in which Ghiberti defeated Brunelleschi) and for the cupola of Florence Cathedral (in which it was Brunelleschi’s turn to win), but there are many other examples. In 1477, for instance, Verrocchio defeated Piero Pollaiuolo for the commission for the tomb of Cardinal Forteguerri.

21

In 1491, there was a competition for designs for the façade of the cathedral in Florence. In 1508, Benedetto Diana won and Vittore Carpaccio lost a commission from the Venetian Scuola della Carità. In Venice, incidentally, even the organists at San Marco were appointed only after a competition.

It may be useful to distinguish three main motives for art patronage in the period: piety, prestige and pleasure (see also

chapter 5

). A fourth has been suggested, but it may be anachronistic: investment.

22

If investment in works of art means buying them on the assumption that they will be worth more in the future, then it is difficult to find evidence for it before the eighteenth century.

23

‘The love of God’, on the other hand, is frequently mentioned in contracts with artists; and if piety had not been an important as well as a socially acceptable motive for patrons, it would be difficult to explain the predominance of religious paintings and sculptures in the period (above, pp. 27–8). Prestige, or what the sociologist

Pierre Bourdieu called the desire for ‘distinction’ from others, was also a socially acceptable motive, above all in Florence. It is not infrequently mentioned in contracts. When the

Operai del Duomo

of Florence commissioned twelve apostles from Michelangelo, for example, they referred to the ‘fame of the whole city’ and its ‘honour and glory’. When Giovanni Tornabuoni commissioned frescoes for his family chapel in Santa Maria Novella, he referred openly to the ‘exaltation of his house and family’, and ensured that the family coat of arms was prominently displayed.

24

The most extraordinary example of the desire for prestige, however, is surely the tabernacle commissioned by Piero de’Medici for the church of the Annunziata in Florence and inscribed ‘the marble alone cost 4,000 florins’ (

Costò fior. 4 mila el marmo solo

).

25

This classic example of nouveau-riche exhibitionism makes one wonder whether – as seems to have been the case in eighteenth-century Venice – rising families saw art patronage as a way of showing the world that they had reached the top, and whether they were more active as patrons than families already established.

26

The prestige acquired by art patronage might be of political value to a ruler. Filarete, who had of course an axe to grind, or, rather, a palace to build, argued this case and tried to demolish the economic argument that buildings were too expensive:

Magnanimous and great princes and republics as well, should not hold back from building great and beautiful buildings because of the expense. No country was ever impoverished nor did anyone ever die because of the construction of buildings … In the end when a large building is completed there is neither more nor less money in the country but the building does remain in the country or city together with its reputation or honour.

27

Machiavelli too saw the political use of art patronage and suggested that ‘a prince ought to show himself a lover of ability, giving employment to able men and honouring those who excel in a particular field.’

28

The third motive for patronage was ‘pleasure’, a more or less discriminating delight in paintings, statues, and so on, whether as objects in their own right or as a form of interior decoration. It has often been suggested that this motive was more important as well as more self-conscious in Renaissance Italy than it had been anywhere in Europe for a thousand years.

29

This is

likely enough, although the ‘more’ cannot be measured; all that can be done is to quote examples of the trend.