The Italian Renaissance (27 page)

Read The Italian Renaissance Online

Authors: Peter Burke

An interesting example of the devotional use of certain images, and a material sign of spectator response, is what one might call pious vandalism – the defacing of the painted devils in a painting by Uccello, for instance, or the scratching out of the eyes of the executioner of St James in a fresco by Mantegna

16

– the equivalent, one might say, of the audience hissing the villain in a melodrama. In fact, the religious plays of the period had similar aims. These

rappresentazioni sacre

, as they were called, which were written and acted in the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, were rather like the miracle and mystery plays of late

medieval England (a reminder of the difficulty of distinguishing between ‘Renaissance’ and ‘Middle Ages’, particularly in the case of popular culture). They usually end with angels exhorting the audience to take to heart what they have just seen. At the end of a play about Abraham and Isaac, for example, the angel points out the importance of ‘holy obedience’ (

santa ubidienzia

).

17

Ex votos

are a kind of devotional image of which Italian examples remain from the fifteenth century onwards, recording a vow made to a saint in a time of danger, whether illness or accident. Those that have survived, in the sanctuary of the Madonna of the Mountain at Cesena, for example, which contains 246 examples earlier than 1600, are probably only a tiny proportion of those that once existed.

18

It may well have been this kind of occasion that most often persuaded ordinary people to commission paintings. The artistic level of the majority of

ex votos

is not high, but the category does include a few well-known Renaissance paintings, notably Mantegna’s

Madonna della Vittoria

, commissioned by Gianfrancesco II, marquis of Mantua, after the battle of Fornovo, in which he had, at least in his own eyes, defeated the French army. It was the Jews of Mantua who actually paid for the painting, though not out of choice. Again, Carpaccio’s

Martyrdom of 10,000 Christians

and Titian’s

St Mark Enthroned

were both commissioned to fulfil vows in time of plague, while Raphael’s

Madonna of Foligno

was painted for the historian Sigismondo de’Conti, apparently to express his gratitude for his escape when a meteor fell on his house.

Another use of religious paintings was didactic. As Pope Gregory the Great had already pointed out in the sixth century, ‘Paintings are placed in churches so that the illiterate can read on the walls what they cannot read in books’, a sentence much quoted in the Renaissance.

19

A good deal of Christian doctrine was illustrated in Italian church frescoes of the fourteenth centuries: the life of Christ, the relation between the Old and New Testaments, the Last Judgment and its consequences, and so on. The religious plays of the period consider many of the same themes, so that each medium reinforced the message of the others and made it more intelligible. It does not seem useful to argue which came first, art or theatre.

20

A special case of the didactic is the presentation of controversial topics from a one-sided point of view – in other words, propaganda.

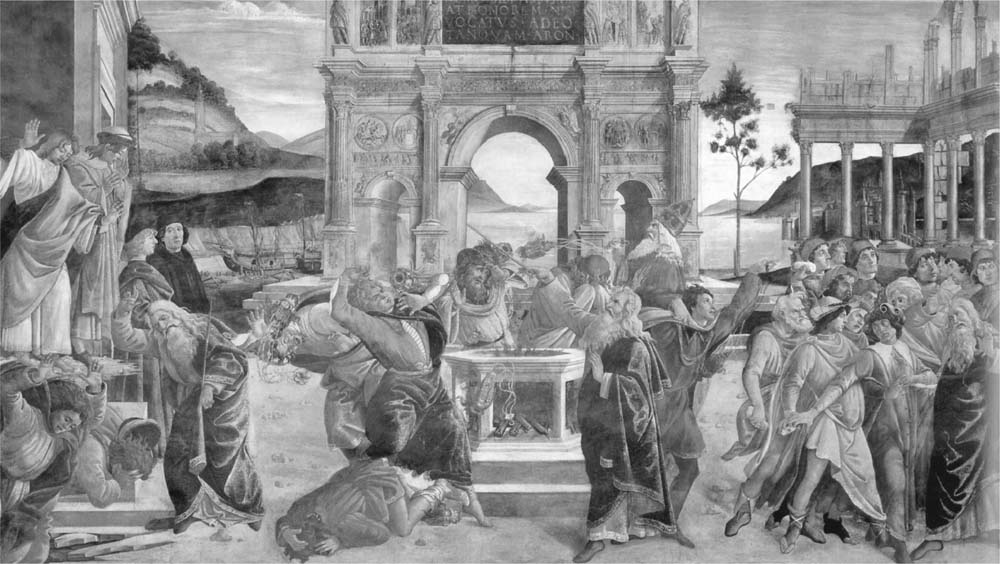

Like rhetoric, painting was a means of persuasion. Paintings commissioned by Renaissance popes, for example, present arguments for the primacy of popes over general councils of the Church, sometimes by drawing historical parallels. For Pope Sixtus IV, for example, Botticelli painted the

Punishment of Korah

, illustrating a scene from the Old Testament in which the earth opened and swallowed up Korah and his men after they had dared to challenge Moses and Aaron (Plate 5.1). An earlier fifteenth-century pope, Eugenius IV, had made reference to Korah when condemning the Council of Basel.

21

In a similar manner, Raphael painted for Pope Julius II, who was in conflict with the Bentivoglio family of Bologna, the story of Heliodorus, who tried to plunder the Temple of Jerusalem but was expelled by angels.

22

Again, after the Reformation, paintings in Catholic churches in Italy and elsewhere tended to illustrate points of doctrine which the Protestants had challenged.

23

P

LATE

5.1 S

ANDRO

B

OTTICELLI

:

T

HE

P

UNISHMENT OF

K

ORAH

, D

ATHAN AND

A

BIRON

, S

ISTINE

C

HAPEL

, V

ATICAN

Following the Reformation, the Catholic Church became much more concerned to control literature and, to a lesser degree, painting. An Index of Prohibited Books was drawn up (and made official at the Council of Trent in the 1560s), and Boccaccio’s

Decameron

, among other works of Italian literature, was first banned and then severely expurgated.

24

Michelangelo’s

Last Judgement

was discussed at the Council of Trent, which ordered the naked bodies to be covered by fig-leaves.

25

An Index of Prohibited Images was considered, and Veronese was on one occasion summoned before the Inquisition of Venice to explain why he had included in a painting of the

Last Supper

what the inquisitors called ‘buffoons, drunkards, Germans, dwarfs and similar vulgarities’.

26

The visual defence of the papacy has introduced the subject of political propaganda, at least in the vague sense of images and texts glorifying or justifying a particular regime, if not in the more precise sense of recommending a particular policy.

27

There are so many examples of glorification from this period that it is difficult to know where to begin, whether to look at republics or principalities, at large-scale works such as frescoes or

small-scale ones such as medals. Like the coins of ancient Rome, the medals of Renaissance Italy often carried political messages. Alfonso of Aragon, for example, had his portrait medal by Pisanello (1449) inscribed ‘Victorious and a Peacemaker’ (

Triumphator et Pacificus

).

28

On his triumphal arch there was a similar inscription, ‘Pious, Merciful, Unvanquished’ (

Pius, Clemens’, Invictus

). The king, who had recently won Naples by force of arms, seems to be telling his new subjects that if they submit they will come to no harm, but that in a conflict he is bound to win. In Florence, at the end of the regime of the elder Cosimo de’Medici, a medal was struck showing Florence, personified in the usual manner as a young woman, with the inscription ‘Peace and Public Liberty’ (

Pax Libertasque Publica

).

29

Under Lorenzo the Magnificent, medals were struck to commemorate particular events, such as the defeat of the Pazzi conspiracy or Lorenzo’s successful return from Naples in 1480. The sculptor Gian Cristoforo Romano commemorated the peace arranged between Ferdinand of Aragon and Louis XII with a medal giving the credit to Pope Julius II and describing him as ‘the restorer of justice, peace and faith’ (

Iustitiae pacis fideique recuperator

). Mechanically reproducible as they were, and relatively cheap, medals were a good medium for spreading political messages and giving a regime a good image.

Statues displayed in public were another way of glorifying warriors, princes and republics. Donatello’s great equestrian statue at Padua honours a

condottiere

in Venetian service, Erasmo da Narni, nicknamed ‘Gattamelata’, who died in 1443, and it was commissioned by the state (by contrast, the monument to Bartolommeo Colleoni in Venice was effectively paid for by the

condottiere

himself). A number of Florentine statues had a political meaning which is no longer immediately apparent. In their wars with greater powers (notably Milan), the Florentines came to identify with David defeating Goliath, with Judith cutting off the head of the Assyrian captain Holofernes (Plate 5.3), or with St George (leaving the role of the dragon to Milan). Donatello’s memorable renderings of all three figures are thus republican statements. When the Florentine Republic was restored in 1494, political symbols of this kind reappeared, notably Michelangelo’s great

David

, which refers back to Donatello’s David and so by extension to the dangers which the Republic had successfully survived in the early fifteenth century. The statue thus ‘demands a knowledge of contemporary political events before one can understand it as a work of art’.

30

P

LATE

5.2 S

CHOOL OF

P

IERO

DELLA

F

RANCESCA

:

P

ORTRAIT OF

A

LFONSO OF

A

RAGON

Paintings, too, carried political meanings. In Venice, the Republic was glorified by the commissioning and display of official portraits of its doges, and of scenes of Venetian victories in the Hall of the Great Council in the Doge’s Palace. In Florence, when the Republic was restored in 1494, a Great Council was set up on the Venetian model,

together with a hall in the Palazzo della Signoria as a meeting-place, complete with victory paintings on the walls, the battles of Anghiari and Cascina commissioned from Leonardo and Michelangelo. When the Medici returned in 1513, the paintings, still unfinished, were destroyed. This destruction of works by major artists suggests that the political uses of art were taken extremely seriously by contemporaries.

31

So does the employment of Vasari, Bronzino and other painters by Cosimo de’Medici, grand duke of Tuscany (Plate 5.4), to redecorate the Palazzo Vecchio with frescoes of the achievements of the regime and to paint official portraits of the grand-ducal family.

32

What is more difficult to decide, at this distance in time, is whether certain paintings carried more precise messages – whether, for instance, they recommended certain policies. One example which has attracted considerable attention is Masaccio’s great fresco of

The Tribute Money

in the Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence (Plate 5.5). The subject is an unusual one; it carries a clear moral, ‘Render unto Caesar’, and it was painted in 1425, at a time, when proposals to introduce a new tax, the famous

catasto

, were under discussion. Is it a pictorial defence of the tax? Or is its message one about papal primacy, like Botticelli’s

Punishment of Korah

?

33

In other cases, the political reference of a painting is clear, but its political purpose is rather more doubtful: for example, the images of traitors and rebels. In 1440, for instance, Andrea del Castagno is said to have painted images of rebels hung by their feet on the façade of the gaol in Florence. As a result he was nicknamed ‘Andrew the Rope’ (

Andrea degli impiccati

). In 1478, it was Botticelli’s turn to paint the images of the Pazzi conspirators in the same place. In 1529–30, during the siege of Florence, it was Andrea del Sarto who painted on the same building the images of captains who had fled (cf. Plate 5.6). One wonders why this was done. Was it, as suggested earlier, magical destruction? Or were the paintings made primarily to give information, like a ‘wanted’ poster? This would at least be a plausible explanation of the public display in Milan of the images of bankrupts. The most likely explanation of these paintings, however, given the importance of honour and shame in the value system of this society (below, p. 204), is that they were executed to dishonour the victims and their families, to destroy them socially, to make them infamous.

34

Such an explanation

is made more plausible by the existence of a literary equivalent. In Florence, the public herald had the duty of writing what were called

cartelli d’infamia

– in other words, verses insulting the enemies of the Republic.

P

LATE

5.3 D

ONATELLO:

J

UDITH AND

H

OLOFERNES