The Italian Renaissance (28 page)

Read The Italian Renaissance Online

Authors: Peter Burke

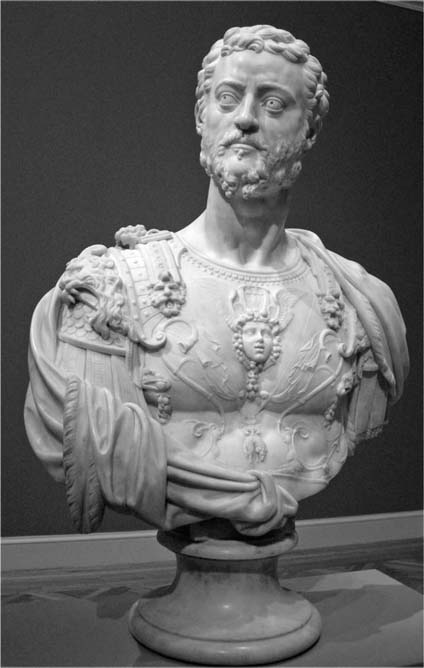

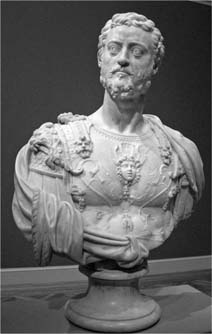

P

LATE

5.4 B

ENVENUTO

C

ELLINI

:

C

OSIMO

I

DE

’M

EDICI

P

LATE

5.5 M

ASSACCIO

:

T

HE

T

RIBUTE

M

ONEY

(

DETAIL

)

P

LATE

5.6 A

NDREA DEL

S

ARTO

:

T

WO

M

EN

S

USPENDED BY

T

HEIR

F

EET

(

DETAIL

),

RED

C

HALK ON

C

REAM

P

APER

Humanism too had its uses, whether to produce virtuous rulers (as the humanists claimed) or to foster habits of docility and obedience (as some scholars now argue).

35

It is less necessary to dilate upon literature here, since its potential for political persuasion is obvious enough. Suffice it to say that the epics in Latin and Italian discussed in the last chapter were poems

in praise of rulers through their ancestors, real and imaginary, and justifications of their rule, no less political than their model, Virgil’s

Aeneid

, which was commissioned to give Augustus a good public image and – according to some classical scholars – even to defend certain of his policies. Historical works, the prose equivalents of epic according to Renaissance literary theory, were often used for similar purposes; that was why governments pensioned humanist historians such as Lorenzo Valla in Naples, Marcantonio Sabellico in Venice, or Benedetto Varchi in the Florence of the grand duke Cosimo de’Medici. They were supposed to be new Livys, just as the states they celebrated were new Romes. Some poems carried more precise and more topical messages – for example, the ‘laments’ put into the mouths of rulers at their fall (such as Cesare Borgia, who lost everything on the death of his father, Pope Alexander VI, or Giovanni Bentivoglio, who was driven from Bologna by Julius II) or cities at times of crisis (Venice in 1509, following a major defeat at Agnadello, or Rome in 1527, after it was sacked by imperial troops).

36

Luigi Pulci’s famous epic the

Morgante

(1478) seems to be, among other things, a plea for a crusade against the Turks, an aim which the poet is known to have supported. Ariosto makes a similar point in his

Orlando Furioso

(1516), urging Frenchmen and Spaniards to fight Muslims rather than their fellow Christians (in other words, to desist from their wars in Italy).

The mobilization of the arts in an attempt to persuade was most elaborate in the cases where least is now left for posterity to view and judge – in other words, in court and civic festivals, which often carried fairly precise and extremely topical political messages as well as contributing to the general task of celebrating or legitimating a particular regime. In the case of Venice, with its elaborate ducal processions and its annual Marriage of the Sea, one historian speaks, not without reason, of ‘government by ritual’, stressing the image of a harmonious hierarchical society projected by these quasi-dramatic forms. As for topical references, a good example comes from 1511, during the famous war of the League of Cambrai, in which the very existence of Venice (or at least of her empire) was at stake. The Scuola di San Rocco (above p. 96) exhibited an allegorical

tableau vivant

, including Venice (personified as a woman) and the king of France (the principal enemy of the Republic), flanked by the pope with a placard asking why France had denied the true faith.

37

In Florence, the political uses of festivals are most obvious in the period following the Medici restoration of 1513. A notable example is that of the state entry into Florence in 1515 of

the Medici pope, Leo X, through an elaborate sequence of triumphal arches in which the theme of the return of the golden age was emphasized.

38

In this field, too, the second Cosimo – that is, the grand duke of Tuscany – showed his awareness of the political value of the arts. Not only was his wedding to Eleonora of Toledo in 1539 the occasion for an elaborate display, but the annual celebrations marking Carnival and the feast of St John the Baptist (patron saint of Florence) were more or less taken over by Cosimo and his men and used with what another writer calls – with particular appropriateness in this context – a ‘conscious Machiavellianism’.

39

One has the impression – it is difficult to be more precise – that the political uses of the media were greater and also more self-conscious in the sixteenth century than they had been in the fifteenth. Faced with the wider diffusion of unorthodox ideas made possible by the invention of printing, governments, like the Church, turned to censorship. When Guicciardini’s great

History of Italy

was published, posthumously, in 1561, a number of anticlerical remarks had been expurgated. It was, however, not the Church but Cosimo de’Medici of Tuscany who was responsible for the expurgations, so as to preserve good relations between his regime and the papacy. On the positive side, Cosimo showed his awareness of the political uses of culture by founding first the Florentine Academy and then the Academy of Design. In other words, he tried to turn Tuscan ‘cultural capital’ (the primacy of its language, its literature, its art) into political capital for his regime.

40

The political messages discussed so far are those delivered on behalf of those in power. However, opponents of the various regimes were far from silent. They could, for example, make their views known by a kind of secular iconoclasm. After the defeat of the Venetian forces at Agnadello in 1509 the revolt of the subject cities, such as Bergamo and Cremona, was marked by the defacing of the sculpted lion of St Mark, placed in each city as a sign of Venetian domination. On the death of Pope Julius II, his statue in Bologna, another sign of domination, also met its end. Graffiti already had their place in the politics of Italian city-states and were sometimes recorded in chronicles or private letters. A literary development from these graffiti were the so-called pasquinades (

pasquinate

), verses satirizing the popes and cardinals which came from the later fifteenth century onwards to be attached to the pedestal of a fragment of a classical statue. The verses, attributed to the statue, were written on occasion by distinguished writers, such as Pietro Aretino, whose pungent verses

on the conclave following the death of Leo X did much to make his reputation.

41

There remain some uses of the arts which do not fit our categories of ‘religion’ and ‘politics’, at least in the strict sense. One could perhaps widen the latter category to include the use of portraits of marriageable daughters in negotiations between princes, or indeed between families of a middling social status.

42

Even the portraits of private persons can be seen as a kind of propaganda, with the artist collaborating with the sitter to present a favourable image of an individual, or of his or her family, to impress rival families, or perhaps posterity.

43

However, it is worth pausing to think how much of the material culture of Renaissance Italy was produced for a domestic setting (above, pp. 10–12).

44

It was for the use or the glory not so much of individuals as of families, especially noble families, or families with noble pretensions.

The most important and expensive item was of course the town house, or ‘palace’ as the Italians like to call it, a symbol of the family as well as a shelter for its members, designed to impress outsiders rather than to provide the inhabitants with comfortable surroundings. Comfort is a more recent ideal, dating from the eighteenth century or thereabouts. Older ideals were modesty and defence. The fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, on the other hand, were the heyday in Italy of what is often called ‘conspicuous consumption’, in which nobles built to sustain the honour of the house and to make their rivals envious.

45

The house (especially its façade) and its contents formed part of a family’s ‘front’, the setting and the stage props for the long-playing drama in which their status was enacted. The analysis of ‘front’ offered by Goffman seems particularly appropriate to the behaviour of nobles in Italy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

46

In the language of the time, the palace demonstrated the ‘magnificence’ of the family that owned it, although the ‘propriety of display’, or the scale of display, was a matter for debate.

47

Villas or houses in the

countryside moved in a similar direction. In the early part of the period, they were essentially farmhouses, allowing the owners to supervise the workers on their estate. Gradually, however, the emphasis shifted from profit to pleasure.

48

Other material objects were associated with important and highly ritualized moments of family history, notably births, marriages and deaths. The

desca di parto

or ‘birth tray’, on which refreshments were brought to the new mother, was often painted with appropriate themes such as the triumph of love. The

cassone

, a large chest with paintings on the outside – and sometimes inside the lid as well – was associated with marriage, for it contained the bride’s trousseau.

49

Pictures were frequently given as wedding presents, and newly-weds not infrequently had their portraits painted, the bride wearing the new clothes given her by the husband’s family and sometimes bearing their badge, thus marking her as theirs.

50

The open allusions to sexuality permitted at weddings seem to have affected the conventions of nuptial art, which includes such Renaissance masterpieces as Mantegna’s

Camera degli Sposi

at Mantua, Raphael’s

Galatea

, and Sodoma’s

Marriage of Alexander and Roxanne

, the last two painted for the Sienese banker Agostino Chigi.

51

Poetry and plays might also be associated with the happy occasion; Poliziano wrote his pastoral drama

Orfeo

for a double betrothal at the court of Mantua. To commemorate deaths in the family, there were funeral monuments, some of them extremely grand affairs. Since our period covers Michelangelo’s Medici Chapel and his tomb for Pope Julius II, always concerned for the glory of the della Rovere family, no more need be said on that account. If states employed artists and writers to defame enemies, so, on occasion, did noble families. The painter Francesco Benaglio of Verona was once commissioned to go at night and paint obscene pictures by torchlight on the walls of the palace of a nobleman (the enemy of his client), presumably to put him to public shame.

52

P

LATE

5.7 V

ITTORE

C

ARPACCIO

:

T

HE

R

ECEPTION OF THE

E

NGLISH

A

MBASSADORS AND

S

T

U

RSULA

T

ALKING TO HER

F

ATHER