The Japanese Corpse (19 page)

Read The Japanese Corpse Online

Authors: Janwillem Van De Wetering

Dorin's eyes, which had been half closed, suddenly opened wide.

"I got this note," he said in a low voice. "It was delivered by a small boy when I was visiting our priest this morning. Apparently it was meant for both of us. The boy ran off after he had given us the envelope."

"What does it say?" the commissaris asked.

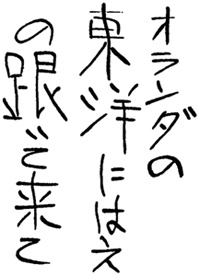

"Oranda no Toyoo ni. Hae no tsuite kite," Dorin said, looking at the sheet in front of him.

"I see," the sergeant said.

"Oh, I am sorry. I'll translate. The translation is something like this—'When Dutchmen go to the Far East, flies follow.' I am sorry, it is rather an unpleasant message. A threat, I would say."

The commissaris repeated the sentence. "When Dutchmen go to the Far East, flies follow." He coughed and began to pat the pockets of his jacket. He found the flat tin and lit a cigar after Dorin and de Gier refused. "That sentence seems to direct its venom at you, Dorin," he said apologetically. "That is, if our friends think you are following us. That's what they

should

think, isn't it? We are supposed to have the initiative in this buying of stolen art; you are acting as an assistant, an agent."

Dorin smiled. "Not quite. Perhaps you are right, but I would interpret much more from the note. You see, in the old days the Japanese thought that the foreigners who came here had a funny smell. Foreigners ate a lot of meat and butter and cheese, and often the meat was putrid and the butter rancid. There was no refrigeration in those days, of course. The Japanese ate rice and vegetables and got their protein from the sea. We are an island race, never far from the water. The fish was either fresh or salted. So we didn't have the body odor the gaijin, the foreigners, carried around with them."

"You mean they thought we stank?" de Gier asked.

Dorin bowed.

"And flies followed those foreigners in the old days."

"Indeed," Dorin said, and the narrow muscular hands adjusted the position of the sheet of paper. "So this note says that you gentlemen stink, and that I, and the priest who is in contact with us now, are flies. Everybody knows what happens to flies. They are swatted, smashed. The life is squeezed out of them and the dead bodies are tossed on the tatami and swept away."

His hand crashed down on the tabletop and a dead fly was flicked on the floor.

The commissaris rolled off his mattress and pulled his suitcase toward him. He opened it and began to feel around. "Here," he said. "A book on Deshima. The Dutch ambassador sent it to me in Tokyo. I think I remember reading something about Dutchmen and flies. Let me see."

He flipped through the pages of the book, and Dorin looked over his shoulder. The book had a number of fullpage illustrations in color, photographs of Japanese scrolls showing the love life of the Dutch merchants, tall men with bags under their eyes, frolicking with young ladies with calm faces, not a hair out of place, dressed in many-layered kimonos. The bottom half of the paintings showed dainty white legs pushed aside by hairy hands and monstrous penises hard at work. The merchants hadn't bothered to take their hats off. The paintings, four in a row, were obviously done by the same artist, and each picture had the same composition, although the merchants and the prostitutes were different persons. The rooms were Japanese, the furniture Dutch, heavy claw-and-ball couches adorned with tassels, huge tables made out of solid oak and with lions sculptured at the corners, thick velvet draperies hiding most of the fusuma, the delicate Japanese sliding doors made out of slats and tightly stretched paper.

De Gier was looking at the pictures, too, and pointed out a merchant's face. "That fellow looks like me."

The commissaris and Dorin laughed. There was indeed a similarity, caused mainly by the merchant's enormous mustache and large brown eyes. The artist had been very good; he had even caught the twinkle in the man's eyes.

"They were having a good time," Dorin said, and the commissaris turned the page. He found what he was looking for.

"Here. Almost the same words. 'When Dutchmen go to the castle, flies follow.'"

"Castle?" Dorin asked. "No, no, 'the Far East'. 'Toyoo' also means castle', but that wasn't meant here. See, they have the Japanese text too. But for us the meaning is the same. You stink and I am a fly and will be swatted. We have had our warnings now. All four of us, the priest, you two gentlemen and myself. If we continue our efforts to buy Daidharmaji's treasures, we will come to harm. I have some knowledge of the ways of the yakusa. They really must do something violent now or they will lose face."

"Right," the sergeant said, slipping his flute back into its leather cover. "Well, they are welcome."

"What about you?" Dorin asked the commissaris.

"They are welcome," the commissaris said. "They succeeded in frightening me, unfortunately, and they must have enjoyed watching me running about in that temple garden. I would like to have a chance to show some courage for a change."

"Well, we are all set, it seems," Dorin said, freeing his legs and jumping to his feet. "They have certainly worked quickly. We only arrived yesterday, and they can't have known about our existence until last night when they must have followed the priest to this inn. I think I will have to alert the Service. We have no means of finding out who the so-called monk and student were who bothered the commissaris, but the actors in the theater which de Gier-san visited today could be picked up and questioned."

"Do you remember where the theater was?"

"Sure," de Gier said. "I can point it out on the map."

"We can also have the staff of this inn questioned. They must have informed the yakusa in some way or other. How else would they know that you two gentlemen are Dutch? They found out, for I have this note here. There's something else about this note which I haven't told you. The characters are drawn by a foreigner. They aren't badly done, but the style is different. A foreigner who can read and write Japanese, somewhat of a rarity. I don't think he is a scholar, but I may be mistaken. I would say the writer is an adventurer, some strange individual who has lived here for many years. His calligraphy is bold. He probably knew the quotation, for the average Japanese doesn't know much about Deshima. It is mentioned in our history books at high school, but that's about all. Perhaps this man is Dutch too, and he is connected with the yakusa. I think the note wants us to know that we are up against strong forces."

"No," the commissaris said.

Dorin looked up. "You don't think so?"

"Oh, yes," the commissaris said. "I am sure the enemy is powerful. But I was referring to your idea about alerting the Service. I don't think we should do that at this point. Let the yakusa show their faces first. Perhaps you can alert the Service to the fact that something is happening and that we are being threatened, so that they wUl be prepared when we need them, but if they start snooping around now, we may complicate the situation too much. I really want

them

to do something now."

"A fight," de Gier said.

The commissaris hesitated, but nodded in the end. "Yes," he said quietly. "A fight. Perhaps we should stay close to each other for the next few days. If there are three of us, they will have to throw in six, or more perhaps. Not because they are afraid of losing the fight, but because they have to make an impression. And if we run into a good number it will be easier to trace them. We are after the big boss, I understand. Maybe we can catch a lieutenant."

"All right," Dorin said. "A fight. But first we eat. There is a restaurant in the mountains nearby where the guests catch their own fish. There is a pond and you will be given a rod. Then we can eat our catch. They will prepare it any way we want them to. The restaurant is old and rather lovely and the location is good, on a hill with a view of Lake Biwa, the great inland lake. I have a car outside. The only drawback is that there are a lot of young ladies in the restaurant who will try to make us drink, and once we are drunk they will try to make us spend the night."

"I think I will be able to stay sober," the commissaris said, and looked at de Gier.

The sergeant smiled and scratched about in his thick and curly hair.

"Maybe I'll have a lemonade," he said.

G

RIJPSTRA'S POLICE VEHICLE, A GRAY VW, WAS WEDGED in between the bumpers of two station wagons, both overloaded with people and luggage and both on their way back from Germany. The holiday season was coming to an end, and the speedways were blocked by endless rows of cars, driven by tired, irritable men who were trying not to remember that the few weeks they had just managed to live through had cost them at least twice the amount calculated originally. Short-tempered wives sat next to them and two or three whining children filled the back seats. Tents and small boats were strapped to the roofs of the cars and would, every now and then, begin to slide, so that cursing drivers were forced to pull over to the emergency lane to try and adjust worn ropes and bent-out hooks.

Grijpstra was sweating, in spite of his open windows and the air vent wheezing near his right knee. His cigar stump was soggy and the short stiff gray hairs on his skull itched. But he didn't feel too bad. He ignored the three little blond heads in the car ahead of him. They had been making faces at him for the last few minutes, but he hadn't reacted so they were bound to stop soon. He blessed the fact that his own holiday was over and done with, spent camping in the south of Holland, in a hired cramped trailer. He had only spent the first night in the trailer when he was forced out by the enormous bulk of his wife and the noisy everlasting fight of his two youngest sons. He had talked to the owner of the camp, and had drunk his way through a crate of beer which he had paid for in advance, and when the owner was mellow and ready to love others as he loved himself, had wangled a small, old and decrepit trailer at the end of the field, for himself only and at no extra charge. Even with that unexpected privacy the holiday had been an ordeal and the weeks had ground away slowly and painfully. But they had, eventually, joined the past and he was working again, able, up to a certain point, to set his own times and places.

He was on his way back from the east now and trying to digest what he had heard and seen while visiting the commissaris' niece and Joanne Andrews, her guest. He had arrived early in the afternoon and stayed for tea. The commissaris' niece, a neat lady in her sixties with a young face and snow-white hair, had thought of some excuse to leave Grijpstra alone with the complainant in the case of the Japanese corpse, and he had been able to state his questions and drop his hints without any disturbance, while they sipped hot tea and nibbled on biscuits, in the shadow of large trees behind the house, their eyes soothed by the reddish brown floor of the small forest, which was kept so spotlessly clean of dead branches, weeds and even pine cones that it seemed to be part of the house itself. The girl had looked very attractive in a mini-skirt and a tight blouse, and he had had some trouble keeping his eyes from straying over her body. Remembering the long legs and bouncy breasts, he suddenly smiled widely and the children in the car ahead of him thought that he had finally reacted to their waving and jumping about and began to cheer. He became aware of them and shrugged. He waved. They went on jumping and screaming and the mother turned around and slapped them, one by one. The three small heads disappeared and he sighed.

Yes, Miss Andrews was a very lascivious female. And a very stubborn female too. She had refused to believe that the two fat jolly gangsters in Amstelveen jail had not killed her fiance\ And she had been unwilling to admit that she had ever slept with other men. Kikuji Nagai had been her one and only, ever. She had slept with other men in Japan, but that was some time ago now, when she was a barmaid in the yakusa nightclub in Kobe. She wanted to forget that part of her life. He hadn't insisted. He was only interested in what she had done in Amsterdam. Surely other men had tried to make love to her; she had been in the public eye, hadn't she? Showing guests to their tables in the restaurant near the State Library? Talking and listening to them? Joking with them at the bar? What about the male staff of the restaurant, the owner, for instance, nice unobtrusive Mr. Fujitani. Grijpstra had had to look the name up in his notebook. Mr. Fujitani, the man he had met briefly during the meal which Mrs. Fujitani had given him in the special room upstairs. Hadn't Mr. Fujitani tried to make love to her?

Yes, he had, Joanne said. But she had refused. And so had the cook. She had refused him too, although she liked him. She had flirted with him but had stopped at the decisive point. She had spent her time either waiting for Kikuji or with Kikuji. She was going to marry Kikuji Nagai, wasn't she?

Yes, certainly. But what about the time when she hadn't met Mr. Nagai yet, the dark days when she had just arrived in Amsterdam and didn't know anyone except the staff of the restaurant. When she felt lonely, spending her nights alone in the boardinghouse? These are modern times, when women take the pill and live without fear. So?