The Jerilderie Letter (2 page)

Later that day the gang successfully robbed the National Bank of Euroa. But Kelly’s first

attempt to spread the word—the letter to Cameron and Sadleir—failed. Cameron didn’t want to know about the document. He handed it over immediately to the premier of Victoria, Graham Berry, who decided that, as it was ‘clearly written for the purpose of exciting public sympathy for the murderers’, it ought to be suppressed. The press could read it but not publish it. Having four bushrangers at large in the colony was embarrassment enough, without handing the leader of the gang, whom the

Argus

described as ‘a clever illiterate person’, a public platform to air his grievances upon.

Kelly arrived in Jerilderie two months later with the failure of the Cameron Letter still fresh in his mind. He’d done with playing the nice guy. The voice that opens the Jerilderie Letter isn’t asking for a fair hearing. It tells us, in no uncertain fashion, the way things are, and how they

are going to be, from here on in. ‘Dear Sir,’ it begins, ‘I wish to acquaint you with some of the occurrences of the present past and future’. There can be no doubt who’s calling the shots now.

This was the document from which Mrs Devine took instruction while her husband sat in the lock-up. Kelly was not going to take any chances this time with the publication of his letter. Which was why he was so enraged when he found out that the bloke he’d just seen dashing out the back door of the bank was Gill. The editor whiled away the rest of the day crouched in the gully of Billabong Creek, tremulously recalling the editorial he’d written some weeks earlier, giving Kelly and his gang short shrift. No doubt, as the long hours turned into dusk, Gill went over his fine phrases, hoping that if found he’d be given an opportunity to retract.

Kelly may have read the editorial, but this was not his main concern. He needed Gill to operate his printing press. The printed word was a currency

more potent than banknotes, and he wanted access to that power. Recovering from his anger, he marched across town to Gill’s house with bank accountant Living and Constable Richards firmly in tow. Joe Byrne, meanwhile, made a beeline for the telegraph office to make sure that Gill hadn’t dashed there to send an alarm to the next town. Dan and Steve remained with the prisoners who, having been stood drinks since the beginning of their captivity, were now a drunken rabble.

Only Mrs Gill was home. She came out and was introduced by Richards, who told her, ‘Don’t be afraid, this is Kelly.’

‘I am not afraid,’ she replied.

Kelly’s response was conciliatory. ‘That’s right. Don’t be afraid. I won’t hurt you or your husband. He should not have run away. Where has he gone to?’

Gathering more pluck by the moment she told him, ‘If you shoot me dead I don’t know where Mr Gill is. You gave him such a fright I

expect he is lying dead somewhere.’

‘You see, Kelly,’ Living interceded, ‘the woman is telling you the truth.’

‘All I want him for is to print this letter—the history of my life,’ persisted Kelly. ‘And I wanted to see him to explain it to him.’

Mrs Gill, however, declined to take the manuscript. Living’s nerves must have been beginning to fray. ‘For God’s sake Kelly, give me the papers, and I will give them to Gill,’ he exclaimed.

After some hesitation Kelly handed the precious parcel to Living. ‘This is a little bit of my life; I will give it to you,’ he said, with an air of ceremony. ‘Mind you get it printed.’ Having received Living’s assurance, he continued, ‘All right; I will leave it to you to get it done. You can read it. I have not had time to finish it.’

Back in the pub, Kelly once again enjoyed having an audience. ‘I want to say a few words, about why I’m an outlaw, and what I’m doing here today,’ he told his listeners, before giving an

account of himself that mirrored the themes and sentiments of the two letters. He and his family had been harassed and persecuted to such an extent that it was not suprising he had become a criminal, and Fitzpatrick—that ‘low drunken blackguard’—had, by turning up at the Greta homestead and making trouble, been the real cause of the Stringybark shootings and all that followed.

There is dispute about who we should consider the ‘true’ author of the Jerilderie letter—Ned Kelly or Joe Byrne—but the similarity between Kelly’s talk and its distinctive phrasing leaves little doubt about the matter. The Reverend John Gribble walked into the Jerilderie pub at the conclusion of Kelly’s speech. He later described how the outlaw, who was leaning against the bar, put his gun next to his glass and announced, ‘There’s my revolver. Anyone here may take it and shoot me dead, but if I’m shot Jerilderie will swim in its own blood.’ It is this extremity of threat, and the rhetoric of blood

in particular, that specifically echoes the Jerilderie Letter.

As the gang members, who had themselves been steadily drinking throughout the afternoon, prepared to leave, Living took the opportunity to escape. According to the interviews given the next day, he rode a fast horse to Deniliquin, taking back-routes and shortcuts, and arrived eight hours later, near midnight. Tarleton left an hour later, having first made sure that a warning was sent to the bank’s other branch in the nearby town of Urana. He took the more conventional route and rode all night, arriving in Deniliquin at 5.45 a.m., just in time to catch the train to Melbourne. After reporting to their superiors, the two bone-weary men narrated the story to a room full of journalists. The

Herald

ran a special 9 p.m. edition and, as rains bringing an end to the heatwave began to fall, a stunned public received news of the gang’s exploits.

Contrary to his promise, Living did not have

Ned’s letter published in Melbourne. Instead, he gave it to the police, who made a copy. This police copy disappeared from view until 1930, when it was published by the Melbourne

Herald

. It remained our only available version until December 2000, when the original document was donated anonymously to the State Library of Victoria, where it can now be viewed.

The Jerilderie Letter gives the impression of a man ready to explode; indeed, it gives us a peculiar insight into the process of that explosion. The episodes and incidents that Kelly recounts are the same as those in the Cameron Letter, the same as in every lecture he ever gave. But now we have a very clear picture of the ferocity and anger that have been mounting in the past ten months of outlawry, in the constant feuding with locals and the police that had for years preceded Fitzpatrick’s disastrous visit. This builds, and builds, until by

the closing passages the letter has become a lethal thing. It shoots to kill. It occupies an imagined universe where there will be no hostages exchanged, and no survivors.

Even now it’s hard to defy the voice. With this letter Kelly inserts himself into history, on his own terms, with his own voice. Even now, more than 120 years after the fact, that voice remains unassimilable. The document makes palpable the experience of being held prisoner overnight, being kept awake by Kelly, and being told, repeatedly, that he had done all the shooting at Stringybark Creek, that the shooting was not murder but self-defence, that Fitzpatrick was the cause of all this. We hear the living speaker in a way that no other document in our history achieves, with its own strange slang, venomous threats, frequently contradictory statements and skewed sense of history. The logic is associational rather than linear, the style both flamboyant and rough. Kelly talks as though his listeners already know all the

details, but have failed to understand them.

The Jerilderie Letter not only prefigures the ambition of modernist literature to make the written and spoken words indivisible, as exemplified in James Joyce’s

Ulysses

, but also harks back to the warrior’s fiery polemic of Homer’s

Iliad

, highly personal, dramatic, oratorical, and charged with competitive hostility. This is the reverberative document which inspired novelist Peter Carey’s highly praised reinvention of the Kelly tale,

True History of the Kelly Gang

.

If Kelly had found Gill on that fateful Monday in Jerilderie and his letter had been published, what would its readers have made of it? It’s difficult to imagine that it would have been welcomed by the majority of selectors in north-eastern Victoria. Many had already been victims of the ‘wholesale and retail horse and cattle dealing’ carried out by the Greta mob, and would have examined the niceties of Kelly’s justifications with a jaundiced eye.

Kelly’s appeal to Ireland’s oppression, his rhetoric of rebellion, would also have brought little sympathy. Many of the farmers he stole from, not to mention the policemen he killed at Stringybark Creek, were Irish. Apart from the shanty culture that thrived along the remoter stock routes, the majority of Kelly’s neighbours, whether Welsh, Irish, Scottish or English, seem to have done their best to put their northern-hemisphere politics behind them. The imperial imperative gave them notions of a shared identity, the idea of being British. This notion was cultivated in public processions and on fete days, and co-existed with the desire to make one’s way in a colonial world in a sober, industrious and respectable fashion.

Kelly’s rhetoric of larrikin defiance may have been unassuageable and obviously drew from an established cant—that of the outlaw and Irish rebel—but it was not representative of the experience of most selectors in the region. It was specific to those whose lives marched to a different drum.

When not in ‘college’ (as Pentridge Gaol was nicknamed) the likes of Ned Kelly expected to have money in their pockets, fast horses to ride, and flash clothes to display. There was more to life, they thought, than the drudgery of farming. ‘I never worked for less than two pound ten a week,’ Kelly declares in the Jerilderie Letter, ‘since I left Pentridge.’

But Kelly might have found sympathetic readers in the city. An alarmed report in the

Herald

on Monday 11 November 1878 spoke of the ‘pernicious effect the evil example set by the Kelly ruffians’ had been having on the larrikins of Melbourne. This ‘all absorbing topic’ was being discussed on street corners each day and, to the consternation of the reporter, ‘the opinions expressed have been invariably in favour of the outlaws and against the police’. This culminated on Sunday evening, when a man ‘had collected quite a number of young people, of both sexes, around him in Bouverie Street, Carlton, and was

singing a street song, in which the Kellys featured as heroes and the authorities in the light of oppressors and tyrants’.

It’s hard to imagine how the Jerilderie Letter, with its unforgettable command of an irrepressible species of invective, could ever have become anything but famous:

The brutal and cowardly conduct of a parcel of big ugly fat-necked wombat headed big bellied magpie legged narrow hipped splawfooted sons of Irish Bailiffs or english landlords which is better known as Officers of Justice or Victorian Police who some calls honest gentlemen but I would like to know what business an honest man would have in the Police as it is an old saying It takes a rogue to catch a rogue and a man that knows nothing about roguery never enter the force…

The letter leaves us with a very different impression of Ned Kelly from the one we are usually given. It tells the story of a violent man living a violent life, yet articulates a highly acute sense of honour and integrity. The letter is punctuated by an urgent need for revenge, articulated through its visceral images, wordplay and metaphors. Its language seethes with menace. ‘By the light that shines pegged to an ant-bed,’ Kelly declares of those who help the police, ‘with their bellies opened their fat taken out rendered and poured down their throat boiling hot will be cool to what pleasure I will give some of them.’

This document provides the emotional blueprint that was to guide the trajectory of Kelly’s outlawry, which culminated, sixteen months later, in the drama of Glenrowan. He attempted to derail a train packed full with police, blacktrackers and journalists. And here, finally, he donned the heavy armour, made from stolen ploughshares, which was to become the iconic signature-piece

encasing the myth that was once a man. The seeds of this future event are already apparent in the letter, where it is announced that ‘in every paper that is printed I am called the blackest and coldest blooded murderer ever on record But if I hear any more of it I will not exactly show them what cold blooded murder is but wholesale and retail slaughter something different to shooting three troopers in self defence and robbing a bank…’

This is the apocalyptic chant of Edward Kelly, a man who has been foolishly disobeyed; these are the words proclaimed by a widow’s son outlawed.

*

This edition of

The Jerilderie Letter

is transcribed from the original held by the State Library of Victoria. While some annotation is necessary to make the document intelligible to modern readers, I have kept it to a minimum, and have tried not to interrupt Kelly’s account of his story.

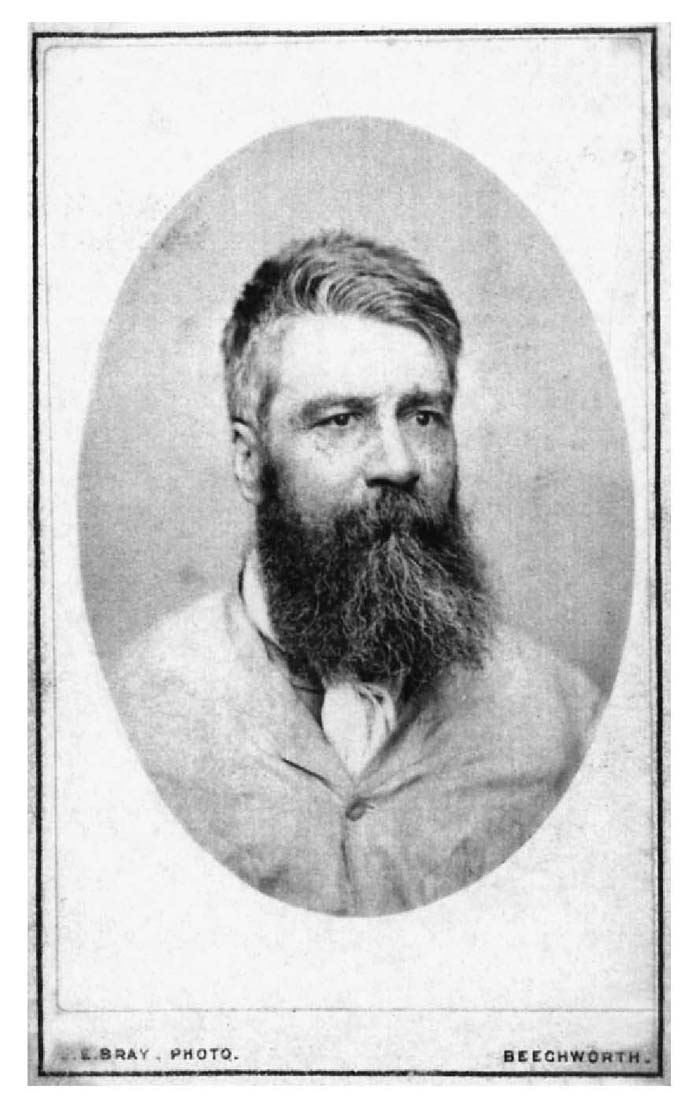

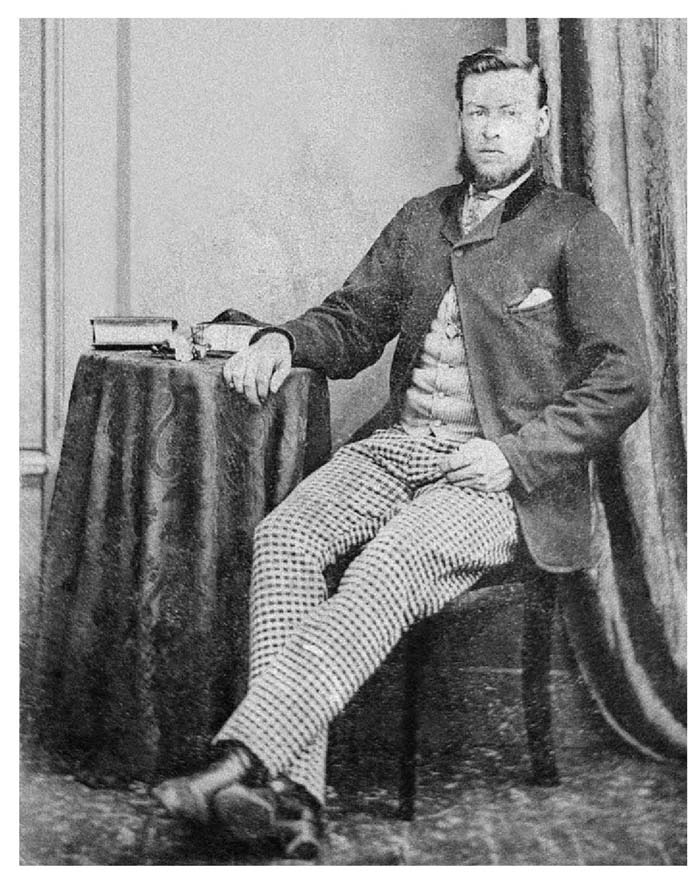

Benjamin Gould was born in Nottingham, England. He came to Australia during the 1853 goldrush and became well known as a hawker in the Greta district.

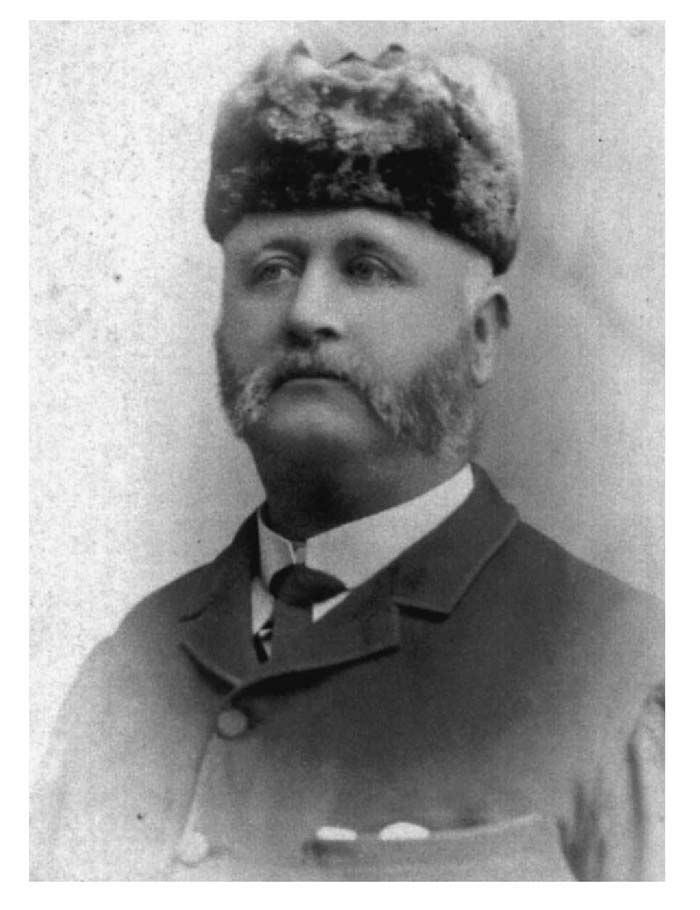

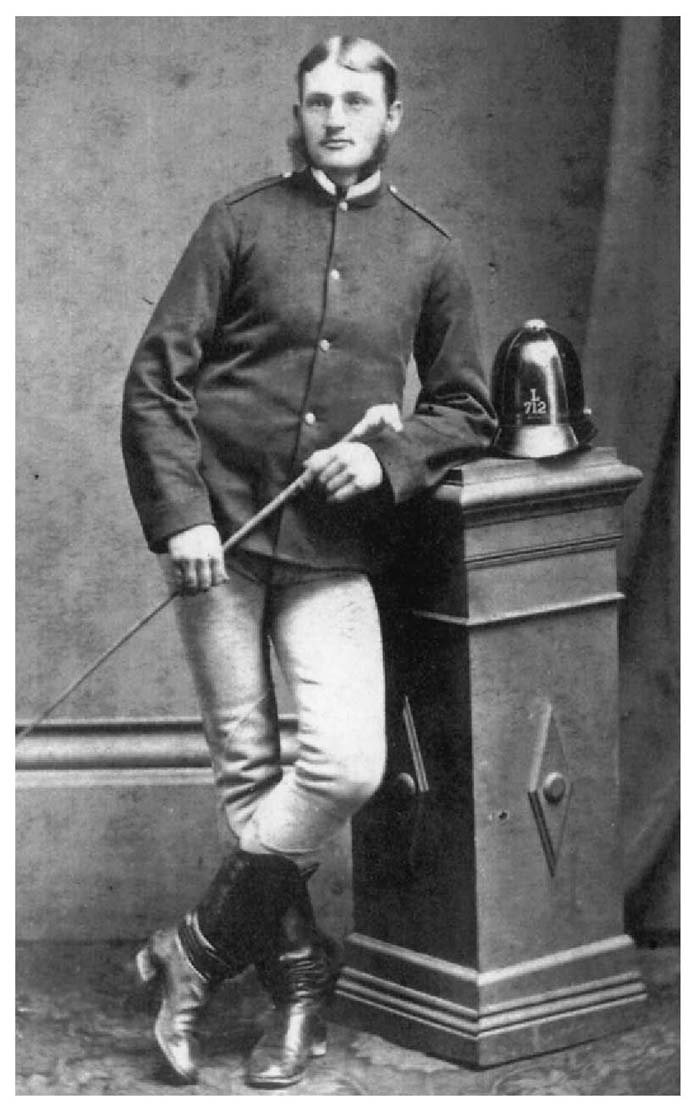

Senior Constable Edward Hall is pictured in his latter-day incarnation as Sub-Inspector. The man with the unenviable task of maintaining order in Greta, he allegedly tried to shoot Ned while attempting to arrest him on the town’s main street.

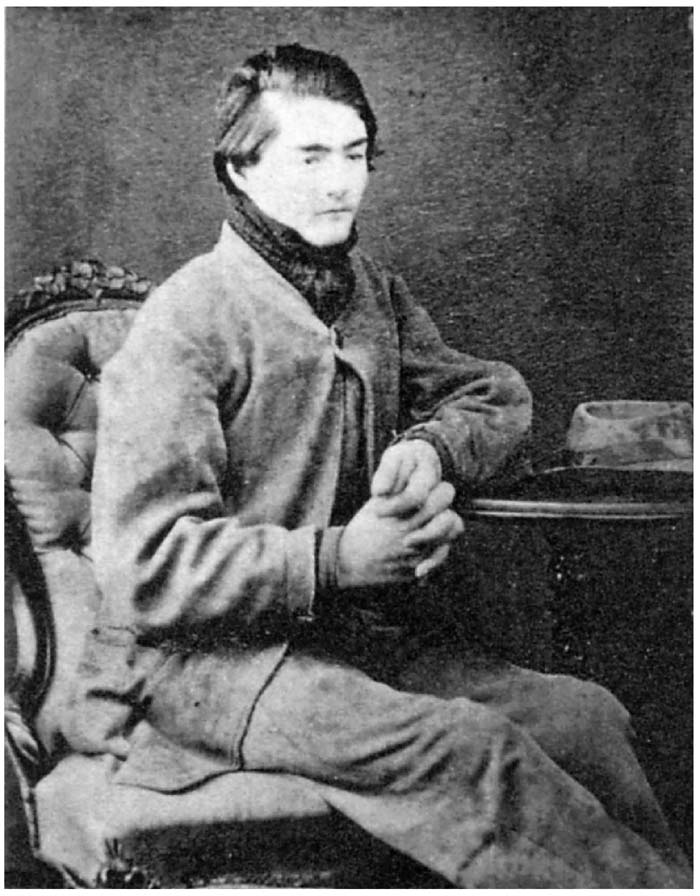

Dan Kelly, the youngest of the Kelly boys, was reputed to admire Ned to the point of hero-worship. Samuel Gill described him as having ‘a sallow complexion, a fine pair of dark eyes, and rather a pleasing look when smiling’. He died at Glenrowan in June 1880.

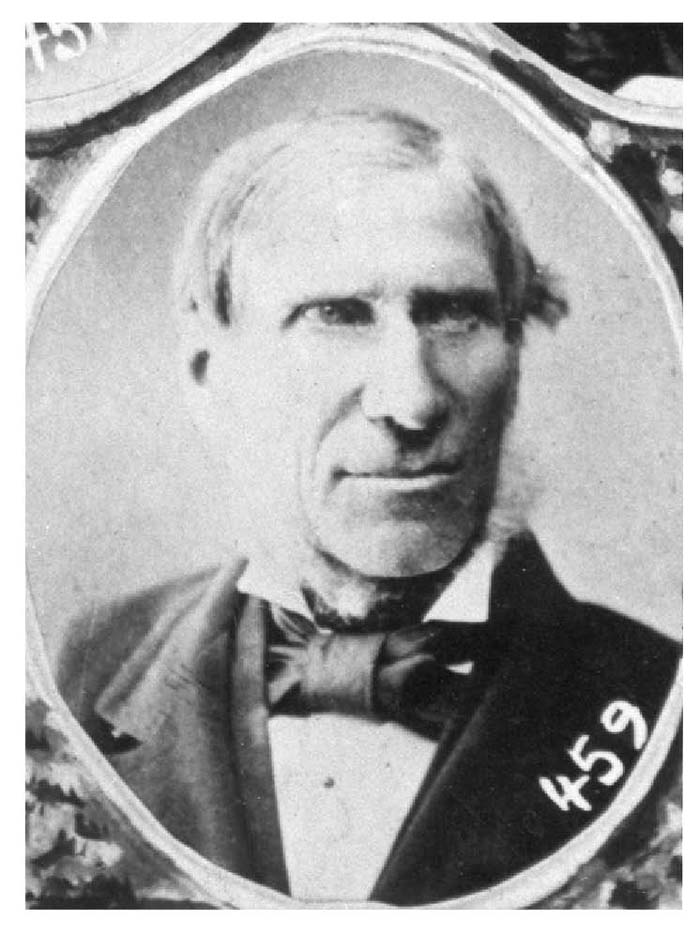

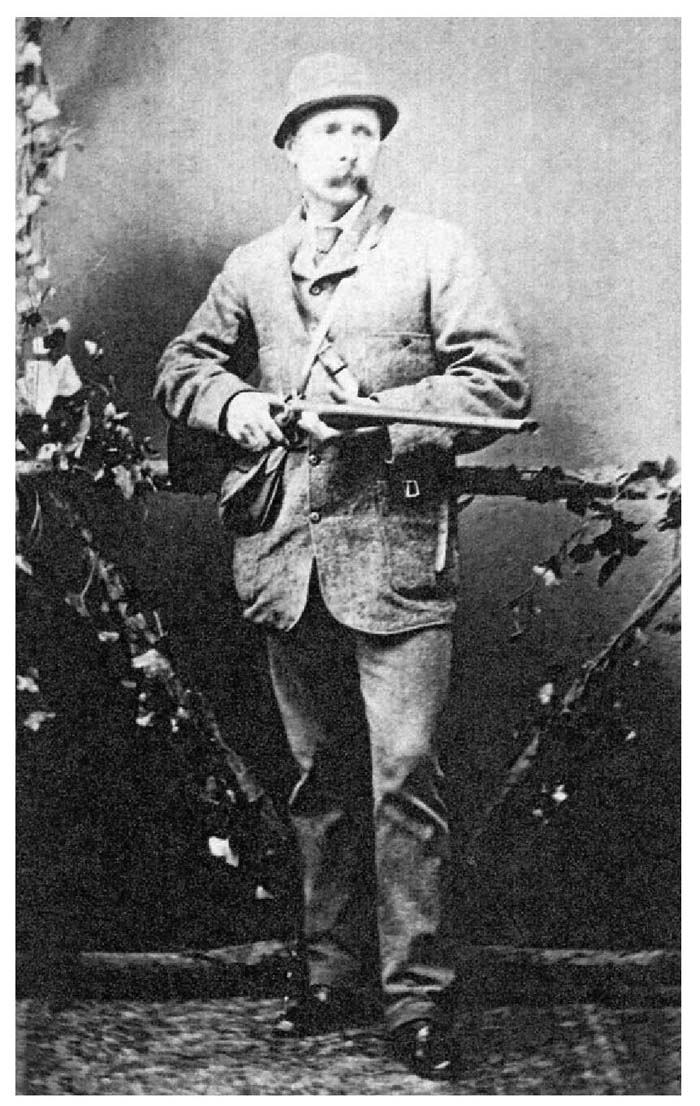

The wealthy landowner James Whitty was an Irish Catholic who originally arrived in Victoria without money or education. The theft of eleven horses from his property in Moyhu, in August 1877, resulted in the warrants for the arrest of Dan and Ned Kelly.

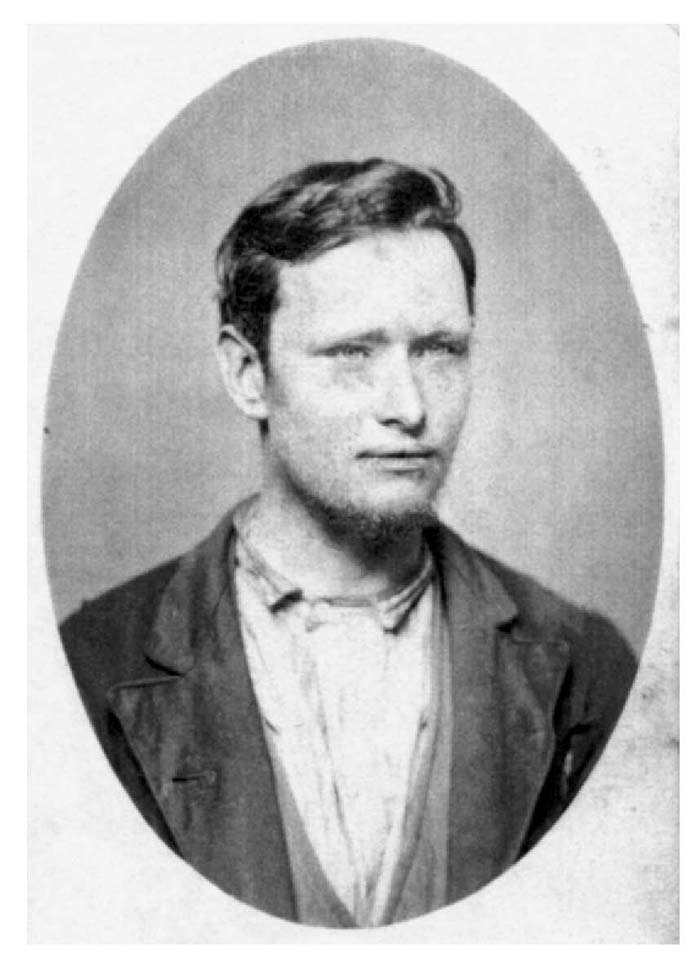

George King, an American only five years Ned’s senior, married Ned’s mother Ellen in 1874. He was involved in the stock theft but made a convenient scapegoat for Ned, having disappeared—leaving Ellen three months pregnant—over a year before the raid.

The 1881 Royal Commission described Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick as appearing ‘to have borne a very indifferent character in the force, from which he was ultimately discharged’. It concluded further that his ‘efforts to fulfil what he may have considered his duty proved disastrous’.

Sergeant Arthur Steele led the second police search party that scoured the Wombat Ranges between Greta and Mansfield in October 1878. He had been the policeman in charge at Wangaratta from 1877 and was involved in Ned Kelly’s capture at Glenrowan.

Joseph Ryan, one of the ‘Greta boys’, was with Dan Kelly on the night of Fitzpatrick’s attempt to arrest him.

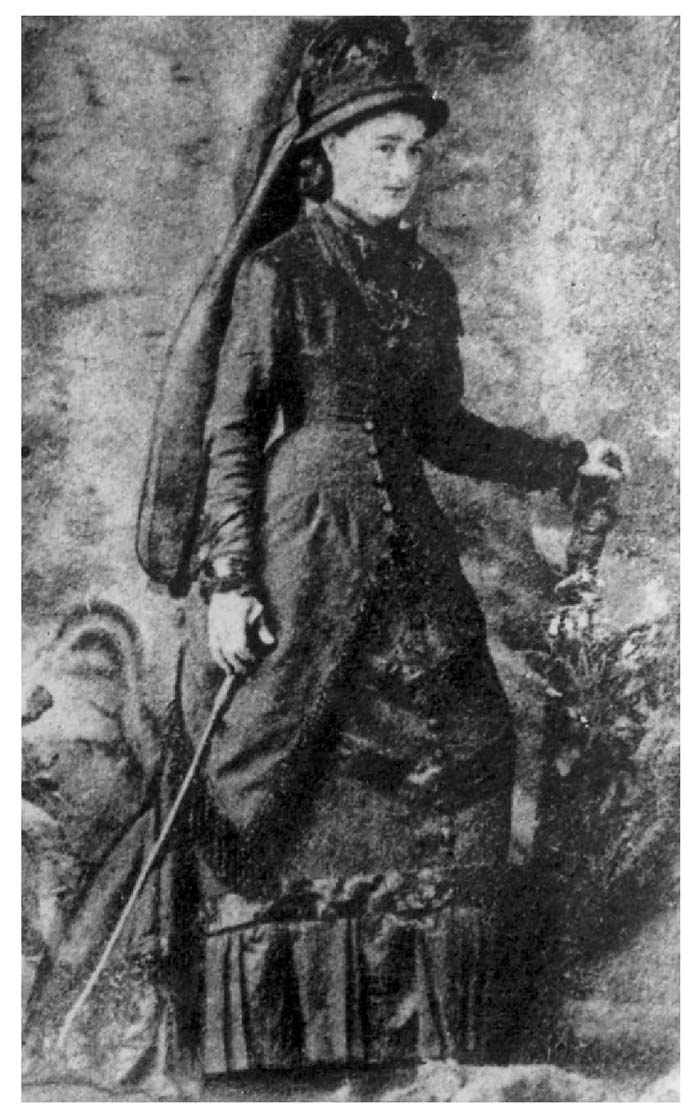

Kate Kelly, sister of Dan and Ned, was the unwilling recipient of the drunken Constable Fitzpatrick’s attentions and, according to her mother Ellen, the real cause of the brawl that injured him and brought about the charges of attempted murder.

Constable Thomas McIntyre was the only policeman to survive the Stringybark shootings. His testimony at Ned’s trial in October 1880 led to Ned’s conviction and subsequent hanging for the shooting of Constable Lonigan.

Constable Thomas Lonigan was the first man to die at Stringybark Creek. Ned Kelly was convicted of his murder and executed on 11 November 1880, two years after the event.

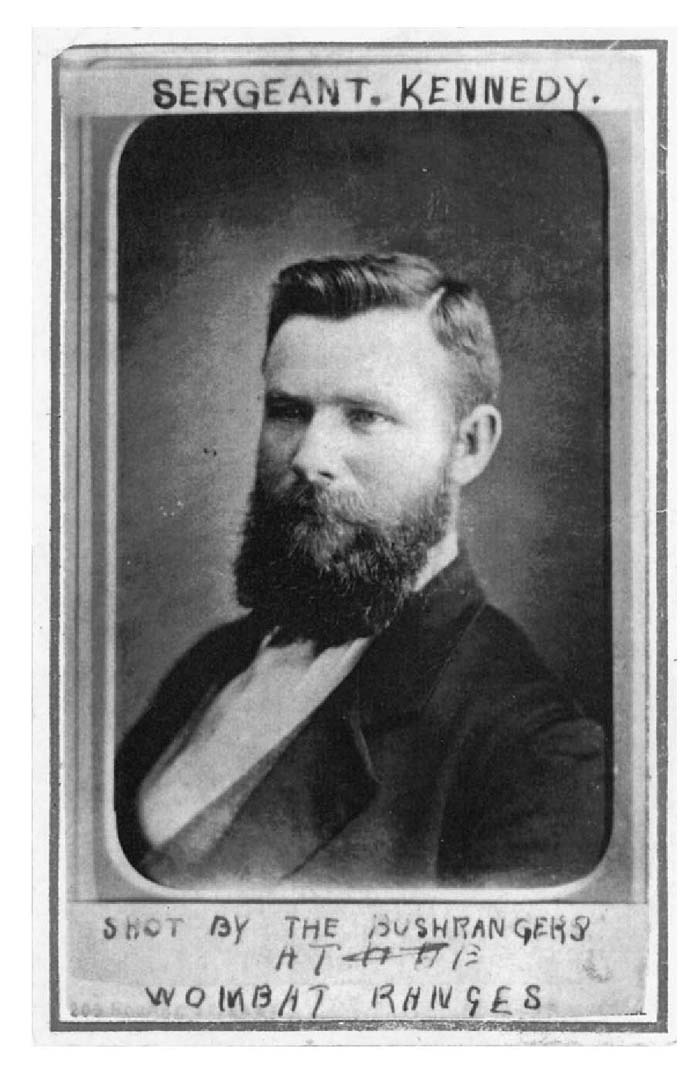

Sergeant Michael Kennedy was the officer in charge of the police search party. He was reputed to be a good bushman and had a thorough knowledge of the country surrounding Mansfield. He was the last man Ned killed at Stringybark Creek.