The Judgment of Paris (31 page)

The twenty-seven-year-old Duret came from a wealthy family of cognac merchants based near Bordeaux. Nursing political ambitions, he had run against the official candidate in the elections of 1863, then after his inevitable defeat entered the family business and toured the world selling cognac. He had developed a keen interest in art, amassing on his travels a large collection of Oriental

objets d'art

and befriending Gustave Courbet during the Realist's legendary wine- and cognac-fueled sojourn at Rochemont in 1862. In comparison with Courbet's antics, Manet's odd behavior must have struck Duret as positively benign. The two men swiftly became friends, visiting the Prado together and making a three-hour excursion by train to Toledo, where once more Manet made a fuss about the local cuisine.

Within days of their meeting, though, Manet had become too exasperated with Spanish food to remain in the country, and he boarded the train for the French frontier. He made a slight detour on his return, spending a few days near Le Mans, in the small town of Sillé-le-Guillaume, where his mother's family still owned substantial property. By the middle of September he was back in Paris. Despite the ordeals of travel and the supposedly unpalatable food, the expedition had been a success, with Manet carrying back with him, besides his plans to paint bullfight scenes, the "enormous hope and courage" given to him by the canvases of

Maître

Velázquez. His return to Paris had been ill-timed, however. He arrived in the city as a cholera epidemic was about to strike.

The summer and autumn of 1865 had been extremely hot and dry in Paris. The level of the Seine had dropped, the canals were closed to navigation, and ornamental fountains such as those in the Place de la Concorde stopped gushing on orders from the government. The practices of rinsing the gutters and hosing down the dusty macadam roads were likewise suspended. By the beginning of October the first spring water from the Dhuis Valley came to the rescue along a new eighty-one-mile aqueduct, passing through thirty-two tunnels en route and, to the applause of assembled onlookers, filling a fifteen-foot-deep reservoir at Belleville. But the water arrived too late to relieve the unsanitary conditions created by the water shortage. By the end of September, cattle reaching the Paris abbatoirs showed signs of a "contagious typhus," prompting the Prefect of Police to quarantine all herds and ship the dead animals for disposal at the knacker's yard in the northern suburb of Aubervilliers."

11

Parisians themselves were the next to suffer as a cholera epidemic that had begun in the south of France, in Marseilles and Toulon, arrived in the first week of October. By the middle of the month, the disease was claiming more than 200 lives each day, with most deaths occurring in the poorer areas on the north side of Paris, such as Montmartre and the Batignolles.

12

Thousands more fell ill with diarrhea, vomiting, palpitations and leg cramps. Caused by a bacterium called

Vibria cholerae

and spread through contaminated water, cholera was still a deadly disease, killing 19,000 people in Paris in the epidemic of 1832 and returning in 1849 to claim 16,000 more.

As October progressed, the cholera wards and cemeteries both started to fill. On October 20, the Emperor Napoléon took time out from his other duties to pay a visit to victims in the Hôtel-Dieu on the Île-de-la-Cite. Though he was cheered by a large crowd gathered outside Notre-Dame, these were difficult days for the Emperor, who had just suffered a catastrophic setback in his foreign policy. With the end of the American Civil War six months earlier (word of Général Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House had reached Paris one week before the opening of the Salon of 1865) he had been obliged to agree, under threat from the Americans—who were arming the Juaristas, and who regarded the intervention as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine—to withdraw all French troops from Mexico. This humbling retreat would inevitably expose Maximilian, his puppet emperor, to attacks from the Juaristas and, in a worst case, lead to his abdication.

By the end of the month, deaths from cholera halved to only a hundred per day, and a newspaper reported that the cholera wards were starting to empty as two thirds of the afflicted recovered from the disease.

13

Still, the epidemic was bad enough (altogether more than 6,000 people would succumb to the disease) that the cemeteries were thronged on All Souls' Day, when families laid beads, bouquets of flowers and garlands of yellow

immortelles

on the graves of their dead relations. So many people had tried to pay their respects at Père-Lachaise that guards were stationed at the entrances to keep the way clear and prevent carriages from colliding.

14

Manet narrowly avoided becoming one of the cholera victims. He fell ill with the disease in the middle of October, during the height of the epidemic, after contracting the bug from the infected water supply in the cholera-ridden Batignolles. Recovering at the end of the month, he wrote to Baudelaire that after returning from Spain he had "fallen victim to the current epidemic."

15

Perhaps in order to keep a lower profile after so much public derision over

Olympia,

Manet switched his custom from the Café de Bade to another establishment, the Café Guerbois, found in the Grand-Rue des Batignolles,* a street ambling northward from the Batignolles to the glasshouses and candle factories of Clichy. The café was run by a man named Auguste Guerbois and consisted of two large rooms and a small garden planted with shrubs at the back. The front room was furnished with gilded mirrors and marble-topped tables, while the room behind, a crypt-like space lit in the daytime by skylights cut into the roof, featured five billiard tables. Friends of Manet from the Café de Bade such as Astruc and Fantin-Latour quickly followed him to the Café Guerbois. Manet soon found himself presiding over the clacking of billiard balls in what became known to the locals as the Artists' Corner. To the art critics, the group quickly became known as the École des Batignolles.

Despite his brush with cholera, Manet dashed off three bullfight scenes in the autumn of 1865: one entitled

The Saluting Torero,

showing a matador in his suit of lights, and two others known as

The Bullfight

and

The Bull Ring in Madrid,

both panoramic action shots featuring the sanguinary scenes he had promised Astruc in his letter from Spain—horses being gored by angry bulls. He also began work on portraits of two "beggar-philosophers," a pair of six-foot, two-inch canvases, each depicting a shoddily dressed old man wrapped in a cloak:

A Philosopher (Beggar in a Cloak)

and

A Philosopher (Beggar with Oysters).

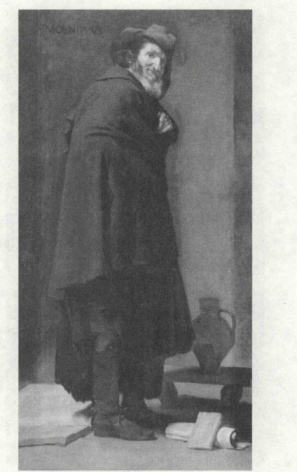

These works had been inspired by two full-length portraits by Velázquez he had seen in the Prado,

Aesop

and

Menippus,

which pictured the eponymous philosophers looking aged and bedraggled.

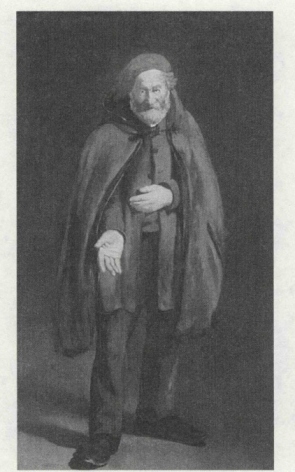

Beggar in a Cloak

was a particularly arresting piece. Using the same stark lighting and cursory brushwork as Velázquez, he portrayed an old man with an expressive face stepping forward either to deliver an oracular pronouncement or make a request for money.

Altogether Manet painted more than a dozen canvases between his return to Paris and the March 20 deadline for the Salon six months later. One of them was

The Tragic Actor,

a full-length portrait of an actor and painter named Philibert Rouvière; a second was

The Fifer,

a slightly smaller full-length portrait of a child dressed in a military uniform. Both had been inspired by the eerily luminous atmosphere of Velázquez's works in the Prado; and it was with these two works—the fruits of his Spanish journey—that Manet would attempt to redeem his reputation at the Salon of 1866.

Menippus

(Diego Velázquez)

Beggar in a Cloak

(Édouard Manet)

*Renamed the Avenue de Clichy in 1868.

I

F THE GROUNDS of the old abbey of Saint-Louis had once been a place of serenity, disturbed only by the tolling of bells and the whispering of nuns in the cloisters, the nineteenth century had brought a number of changes. By the 1860s the abbey enclosure was home to not only Ernest Meissonier and his family but also several other families—the Courants, the Gros and the Bezansons—who had likewise taken up residence in the grounds. Relations among them were for the most part congenial, no small outcome considering that the Protestant Courants and Gros were somewhat taken aback by the grandeur of Meissonier's style of living. Louis and Sarah Courant, furthermore, had taken successful legal action against Meissonier when one of his numerous additions to the Grande Maison infringed on their vegetable garden, while Adolphe Bezanson, a lawyer, had been Meissonier's political opponent in the elections of 1848, defeating him for a seat in the Constituent Assembly.

Neighborly harmony seems to have been preserved due to the happy coincidence that each of the four families had children (or grandchildren in the case of the Courants) of roughly the same age. Meissonier's children Charles and Therese became friends with Lucien and Jeanne Gros, Alfred and Elisa Bezanson, and (whenever they visited from Le Havre) Maurice, Claire and Jenny Courant. Together they swam in the river, unfurled the sails of Meissonier's yachts, or knocked croquet balls across the expansive lawns of the Grande Maison. They also went horseback riding together, accompanying Meissonier on his gallops through the countryside. And Charles and Lucien had another pursuit in common, training together under the eagle eye of

Le Patron

1

Charles Meissonier was hoping to build on the modest success of

The Studio a

year earlier with another contribution to the Salon, and so in the middle of March 1866 he sent to the Palais des Champs-Élysées a domestic interior entitled

While Taking Tea.

Recently, however, Charles had become distracted from his studies. He had taken to painting

plein-air

landscapes in the orchard of the Grande Maison—sometimes, comically, late into the night—in hopes of catching a glimpse of his neighbor Jeanne Gros, the nineteen-year-old sister of Lucien, as she walked along a path skirting the property of the Grande Maison.

2

Having fallen in love with Jeanne two or three years earlier, he arranged his days around the possibility of seeing her. After he discovered that he could see the window of her bedroom in the Gros house from the terrace of his own bedroom, the opportunity of gazing at her from afar made him a reluctant participant in his father's early-morning jaunts through the countryside. "My father wanted to make me ride a horse this morning," he lamented in his diary in the spring of 1866. "He was unaware that this morning I wished to remain at the house in order to see Jeanne for a few minutes. One day without seeing her is so long, so tedious and so heavy to bear."

3

On some mornings when Charles did accompany his father on long excursions, a frosty atmosphere prevailed. The reason was not Jeanne Gros, however, but another neighbor who often came along for the ride, twenty-six-year-old Elisa Bezanson, the daughter of Meissonier's old political opponent. One morning in 1866 Meissonier led his party of riders five miles into the Forest of Saint-Germain. "The weather was cold," Charles recorded in his diary. "Mademoiselle Elisa was with us. I was exquisitely courteous, but very cold. Seventeen words exchanged, I counted them by chance."

4

By 1866 Elisa seems to have been the elder Meissonier's lover, in spirit, at least, if not yet in the flesh. Edmond de Goncourt later claimed that "La Bezanson" (as he called her) was indeed the painter's mistress.

5

Still, it seems unlikely that even a man as arrogant and self-centered as Meissonier would have paraded his mistress before his wife and children in quite so brazen a fashion. At this early stage of their relationship—and a relationship would certainly develop between them—the unmarried Elisa may simply have been in awe of the wealthy and famous Meissonier, who was as flattered by her attentions as he was no doubt vexed by the physical dolors that kept his wife confined for long periods to her bedroom.