The Judgment of Paris (58 page)

The Vendôme Column

The idea of destroying the Vendôme Column had been put forward many months earlier by Gustave Courbet, who served the Government of National Defense during the siege of Paris as "President of the Arts in the Capital."

34

This post gave "Citizen" Courbet (as he took to signing his letters) responsibility not only for the Louvre but also for, among others, the museum in the Palace of Versailles, the Musée du Luxembourg, and the ceramics museum at Sèvres. Under his direction, masterpieces from the Louvre were removed from their frames, rolled up and then transported by train, in boxes marked "Fragile," to the prison in Brest, far from the advancing Prussian armies. Other works of art were taken into the museum's basement, and the

Venus de Milo

was smuggled, under the cover of night, to a vault at the Prefecture of Police on the Île-de-la-Cite. Meanwhile, the Louvre itself was turned into an arsenal and fortified with sandbags.

With the art treasures of Paris thus preserved, Courbet had next turned his attentions to the Vendôme Column, which was, he claimed, "a monument devoid of any artistic value, tending by its character to perpetuate the ideas of wars and conquests."

35

When enthusiasm grew for tearing down the column, Courbet quickly published a letter in

Le Réveil

insisting that he was not actually proposing its destruction, merely the unbolting of the bas-relief frieze and the removal of the column itself to a less conspicuous location. Nonetheless, the seeds of the monument's destruction had been planted, and when the Communards took power the following spring they passed a decree, on April 12, denouncing the Vendôme Column as "a monument of barbarism, a symbol of brute force and false glory." Their decree thunderously concluded: "The Column in the Place Vendôme shall be demolished."

36

The Communards had hoped to knock down the column on May 5, the anniversary of Napoléon's death and the day on which veterans of the Napoleonic Wars traditionally laid wreaths at the column's foot. However, as the equipment necessary for the demolition—a system of cables, pulleys and winches—was not ready on time, the date was moved to the middle of the month. The shaft had been given a bevel cut into which wedges of wood were driven, and then, on the afternoon of May 16, after the singing of the

Marseillaise,

the capstan was tightened and, following an initial miscue, the column crashed to the ground amid cheers from a crowd of 10,000 onlookers. According to one eyewitness, the head of Napoléon "rolled like a pumpkin into the gutter."

37

As the crowd scrambled for souvenirs, the Red Flag was planted on the empty pedestal.

Courbet had not been a deputy in the Communal Assembly at the time of the decree of April 12 that sealed the column's fate. However, he was victorious several days later in a by-election in the Sixth Arrondissement—a constituency that included, ironically enough, the École des Beaux-Arts—and on April 27, as a fully fledged Communard, he had spoken in favor of demolishing the column and replacing it with a statue "representing the Revolution of March 18."

38

In the public imagination, he therefore came to be associated with the toppling of the column. Not the least of his critics was Meissonier, who was outraged by this act of destruction. Having spent the previous decade of his career assiduously celebrating Napoléon's military exploits in works such as

Friedland

and

The Campaign of France,

only to see such heroism be dismissed as "false glory" by Courbet and the Communards and then quite literally turned to rubble in the Place Vendôme, Meissonier saw the desecration of what he regarded as the greatest glory of French history as little short of treason. He condemned Courbet as a "monster of pride" and a "madman," even going so far as to fantasize, in a letter to his wife, about devising the crudest possible punishment: he would chain Courbet to the base of the column and give him the task of copying its bas-reliefs, "while having always in front of him, but beyond his reach, beer mugs and pipes."

39

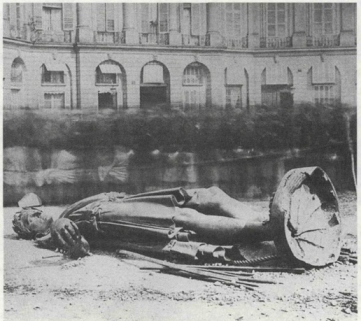

The statue of Napoléon after the toppling of the Vendôme Column, May 16, 1871

One witness to the events of May 16 claimed the toppling caused "no concussion on the ground" since the pavement of the Place Vendôme had been prepared with a bed of sand, branches and manure.

40

In the world of French art, however, the fall of the Vendôme Column would reverberate for many years to come.

Adolphe Thiers was known to his enemies as "Père Transnonain." The nickname alluded to how in 1834, as King Louis-Philippe's Minister of the Interior, he had ordered the brutal suppression of a working-class insurrection in Paris, an act leading to a bloody massacre in the Rue Transnonain. Almost forty years later, his determination to annihilate the Paris Commune was every bit as strong. To that end, since the beginning of April 130,000 government troops had been preparing at secret camps for a second siege of Paris. Thiers was confident of the outcome. "A few buildings will be damaged," he predicted, "a few people killed, but the law will prevail."

41

His friend Meissonier was much less optimistic. For the man who had painted

Remembrance of Civil War

twenty years earlier, the spectacle of the French fighting among themselves in the streets of Paris did not bear contemplation. "If the battle is engaged," he wrote gloomily, "whatever the result, it will be disastrous. Torrents of blood will be spilled and our wounds will be so great that they will be mortal."

42

Meissonier's worst fears were realized soon enough. The carnival of blood—or, as it came to be known,

La Semaine Sanglante

("Bloody Week")—began on a Sunday, May 21, as government troops surged through the undefended Porte de Saint-Cloud, less than four miles southwest of the center of Paris. The Communards had prepared themselves for the inevitable onslaught by raising barricades throughout the city, hacking at Haussmann's new boulevards with pickaxes and prizing free the stones. Sandbags, upturned omnibuses, pieces of furniture, empty casks and piles of books were also used to build barricades. One at the Porte de la Chapelle, north of Montmartre, was even built—very much against his wishes—from the lumber out of which Courbet's 1867 pavilion had been constructed. But these barriers did little to check the inexorable advance of the government troops under the command of Marshal MacMahon, anxious to redeem himself for the disaster at Sedan.

Thiers's prediction that "a few buildings will be damaged" proved, in the days that followed, a spectacular understatement. On May 23 the Palais des Tuileries, the former residence of Napoléon III, was set alight by the Communards as both a smoke screen and a rebuke to French imperial power. As the palace exploded and burned, the central cupola collapsed inward—an even more shocking symbol of destruction than the toppling of the Vendôme Column one week earlier. A wing of the Louvre also went up in flames, with the loss of 100,000 books; and over the next few days ever more buildings were torched: the Palais-Royal, the Palais de Justice, the Cour des Comptes, the Prefecture of Police (where only the accident of a burst waterpipe saved the

Venus de Milo

from incineration), and the Hôtel de Ville, where murals by Ingres, Delacroix and Cabanel were turned to ash. Strong winds whipped the flames higher, sweeping them along the Rue de Rivoli and the Boulevard de Sebastopol; dozens of houses were burned. Edmond de Goncourt could see from his home in the suburb of Auteuil "a fire which, against the night sky, looked like one of those Neapolitan gouaches of an eruption of Vesuvius."

43

Thiers's forecast of "a few people killed" was even more grotesquely understated. On the evening of May 24 the Archbishop of Paris was executed by firing squad in the prison where he had been held hostage for almost two months. His death was soon afterward followed by those of the ten Dominican monks who had been held with him, all of whom were shot, along with thirty-six gendarmes, in reprisal for the execution by government soldiers of Communard prisoners. From Rome, Pope Pius IX denounced the Communards as "men escaped from Hell," while Thiers solemnly announced to the National Assembly in Versailles: "I shall be pitiless. The expiation will be complete."

44

He was true to his word. On May 27, the last Communard forces were defeated in their stronghold inside the cemetery of Père-Lachaise. From there, only thirty yards from Delacroix's tomb, they had been firing on the Versailles troops from a gun emplacement before the grandiose tomb of the Due de Morny, which had been converted into a munitions depot. The government soldiers lined up against a wall in the southeast corner of the cemetery 147 of the surrendering Communards and, in a foretaste of Thiers's pitiless method of expiation, turned on them a

mitrailleuse

that fired 150 rounds per minute. One day later, Marshal MacMahon announced that Paris had been delivered.

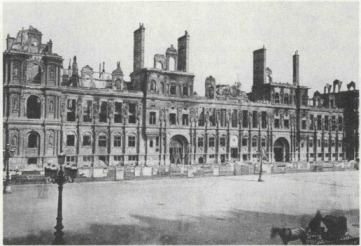

The Hôtel de Ville after it was burned during the suppression of the Commune

Though the Commune was at an end, the carnival of blood continued. The carnage was horrific even for a city that had witnessed the murderous excesses of the French Revolution. "The French," wrote a shocked correspondent from England, "are filling up the darkest page in the book of their own or the world's history."

45

The Seine literally ran red with blood—a long red streak could be seen in the current beside the blackened shell of the Tuileries—as soldiers acting on orders from Thiers executed, in the days that followed, as many as 25,000 Communards.

46

The prisoners were marched into parks, cemeteries and railway stations, where the

mitrailleuses

mercilessly dispatched them. By this point, many of the Communard leaders were already dead, including Rigault, who was shot in the head while defiantly shouting

"Vive la Commune/" at

the advancing troops. Courbet, too, was reported dead, supposedly having swallowed poison to escape falling into Thiers's clutches. When word of his death reached Ornans, his mother died of a heart attack. In fact, rumors of Courbet's death were greatly exaggerated. He was arrested, alive and well, on June 7, three days shy of his fifty-second birthday, and escorted to Versailles to face a military court.

M

EISSONIER RETURNED TO Paris a few days after the fighting had ceased. The stench of bodies was everywhere. As another visitor noted, there were "corpses in the streets, corpses in doorways, corpses everywhere."

1

Yet, incredibly, the city was already starting to return to normal as the many residents who had fled after the events of March 18 returned in the first weeks of June. All were staggered by the sight of so many famous landmarks in ruin, but many found themselves moved, despite everything, by the eerie beauty of the devastation. Théophile Gautier was "saturated with horror" at so much death and destruction, yet confessed himself "struck, most of all, by the beauty of these ruins." His friend Edmond de Goncourt, a virulent anti-Communard, waxed poetical over the sight of the Hôtel de Ville, "a splendid, a magnificent ruin" that reminded him of "a magic palace, bathed in the theatrical glow of electric light." Jules Clarétie was equally impressed. "Ruined, burned and devastated, the Hôtel de Ville remains," he wrote, "the most superb of the Parisian ruins. Its primitive harmony has given way to a picturesque and funerary disorder which wrings one's heart, while offering to one's eyes one of those horribly beautiful spectacles that comes from such destruction."

2

Within a fortnight of Bloody Week an English travel agency, Thomas Cook, was organizing special tours of the ruins. Photographers did a brisk trade, their stark images of the charred landmarks appearing in the windows of shops and even embarking on tours of cities as far afield as London and Liverpool.

3