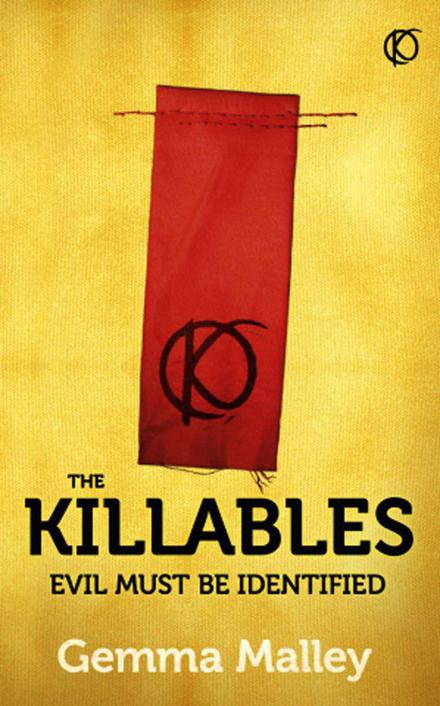

The Killables

Table of Contents

The Declaration

The Resistance

The Legacy

The Returners

Visit

for the latest news, competitions and exclusive material from Gemma Malley

Gemma Malley

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette UK company

1

Copyright © Gemma Malley 2012

The right of Gemma Malley to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Ebook ISBN 978 1 444 72279 6

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 444 72277 2

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

For Diggory

With advances in neuroimaging technology such as MRI, neuroscientists have made significant findings concerning the amygdala in the human brain. Consensus of data shows the amygdala has a substantial role in mental states, and is related to many psychological disorders.

In a 2003 study, subjects with Borderline personality disorder showed significantly greater left amygdala activity than normal control subjects. Some borderline patients even had difficulties classifying neutral faces or saw them as threatening. Individuals with psychopathy show reduced autonomic responses, relative to comparison individuals, to instructed fear cues.

In 2006, researchers observed hyperactivity in the amygdala when patients were shown threatening faces or confronted with frightening situations. Patients with more severe social phobia showed a correlation with increased response in the amygdala.

Similarly, depressed patients showed exaggerated left amygdala activity when interpreting emotions for all faces, and especially for fearful faces. Interestingly, this hyperactivity was normalized when patients went on antidepressants. By contrast, the amygdala has been observed to relate differently in people with Bipolar Disorder.

A 2003 study found that adult and adolescent bipolar patients tended to have considerably smaller amygdala volumes and somewhat smaller hippocampal volumes. Many studies have focused on the connections between the amygdala and autism. Additional studies have shown a link between the amygdala and schizophrenia, noting that the right amygdala is significantly larger than the left in schizophrenic patients.

Wikipedia, January 2011

This extract was taken from the Wikipedia article

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amygdala

which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0 (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

).

Dirt, dust and grime in her eyes, in her nose, choking her. A hand around hers, pulling her on, reassuring her. A rock catches her unawares and she falls, her face pressed into the ground; she lifts her head and wipes her forehead – there is blood on the back of her hand. Her lip begins to quiver but before tears can come she is swept up; her arms wrap around a familiar neck and the journey continues.

The rhythm of his walking calms her; she feels safe. His body is warm; she nestles into him. She can smell him; sweat, hunger, determination, love. ‘Nearly there,’ he murmurs into her ear. ‘Nearly there, my darling.’

She closes her eyes, and when she opens them again she is somewhere else, somewhere sunny, surrounded by grass, the bright light making her squint. A face leans towards her and she smiles, reaches out. ‘We’re here,’ he murmurs. ‘We’re here, my darling . . .’

Evie opened her eyes and sat bolt upright. She’d had a nightmare again, a dream so vivid she checked around her quickly to make sure that she was alone, that she was in her bed. But of course she was. Quickly she knelt down at the side of her bed and started to whisper, ‘I cleanse my mind of bad thoughts. I cleanse my brain of evil. I look to the good, I strengthen my soul, I fight the demons that circle me day and night. I am strong. I am good. I am safe. I am protected and protector.’

She repeated the mantra five times, then, trying not to notice that her sheets were drenched in sweat, Evie made her way to the small bathroom next to her bedroom, the only bathroom in the house – why would you need more than one? – and stood under the cold shower, washing herself, washing away the smell of the man holding her. The man whose face she never saw, but she knew who it was. Every night she went to bed telling herself that she wouldn’t see him again; every night she failed in this resolution, and every morning she woke fearful, wishing she could purge herself, wishing she could be like everyone else, wishing she could be good, free from the nightmares that plagued her, that marked her out as strange, as dangerous.

The dreams never felt like nightmares. They never felt dark and scary; they felt warm, happy.

But that just made it worse.

She was depraved. That was the truth of it. The man represented the evil within her, trying to tempt her, to make her reject good things; she knew that because her mother had told her so. He was evil, and her longing for him told her that she was weak, that she was a failure, that she was corrupt and dangerous. But she could fight it, if she tried hard enough. That’s what her mother said. And the way she said it always suggested that so far Evie hadn’t tried hard enough, that the dreams were her fault, her choice.

Which was why Evie was relieved to find her mother busy in the kitchen that morning when she walked in; absorbed in cooking porridge on the stove, scrubbing down the work surfaces. Hard work, cleanliness of thought and deed, chastity, charity and order – these were the ways to virtue, this was how life should be lived. Her mother was a paragon of virtue, much lauded by the Brother. A good woman, he would say as his eyes fell on Evie, with a slight shake of the head.

Her mother nodded to Evie’s place and put a steaming bowl in front of her daughter, then returned to her work. ‘It’s nearly seven,’ she said abruptly. ‘You need to get a move on.’ She walked back to the cooker, then turned again. ‘You . . . shouted out in your sleep again last night,’ she said, her tone suddenly cold.

Evie’s heart thudded. Her mother had heard her. She knew.

Their eyes met, and Evie suddenly felt a strange but intense longing to share her fears, to tell her mother everything, to have her comfort her, reassure her, wrap her arms around Evie, to recreate the cocoon that had felt so intoxicating, so complete in her dream. But she knew it was impossible, knew that her mother would never understand, would never reassure her. She would judge her, she would blame her. And deservedly so.

‘I . . .’ she started. ‘I . . .’

‘You have to stop, Evie,’ her mother said flatly. ‘You have to fight your evil impulses. In spite of everything you have a good job, a good marriage on the horizon. Do you think you can marry if you cry out in your sleep? Do you think people will look at you in the same way if they find out? How will they look at us? What will people say?’

Evie looked at her uncomfortably. ‘I keep reading the Sentiments,’ she said, biting her lip, her hand inadvertently moving to the small scar to the right of her forehead, her fingers tracing around it to reassure herself.

Her mother looked at her for a moment, her face twisting slightly as she did so. Then she let out a long breath. ‘Reading the Sentiments is not enough. You dream because you allow yourself to dream,’ she said, her eyes narrowing. ‘Because you invite the dream in. It shows that you are weak, Evie. Imagination shows an ability to lie, to pretend the world is different than it is. So you’d better be careful. Now eat your porridge. Don’t waste good food.’

Evie started to eat, but the food felt dry and alien in her mouth. Her mother was right, though she didn’t know the half of it. She was weak. She was a deviant. She tried to chew and to swallow the oatmeal, but it was impossible – it was as though her stomach was rejecting it, as though it knew that she didn’t deserve it.

Even her stomach couldn’t follow the rules of the City properly, she thought to herself miserably. Rules that led to a good life. Rules that everyone followed without question. Don’t waste food. Don’t allow emotions into your heart because emotion is the door to evil. Work hard, follow the rules, obey your parents, do not ask questions, listen to the Brother and heed his teachings, accept your label but strive to improve it, be fearful of evil because it is pernicious, opportunistic, because it never sleeps and once it takes hold of you, you will never be free . . . To everyone else it seemed so simple, so easy. To Evie the rules felt like a straitjacket, forcing her mind and body into a shape that was unnatural to her. And the only explanation she could come up with was that evil had already taken hold of her, that it was the evil within her that rejected the rules established for her protection, for everyone’s.

Eventually she gave up, put her spoon down and pushed her bowl away. Her mother shot her a long stare, then shrugged. ‘You’d better get to work. You don’t want to be late.’

Evie left the kitchen, brushed her teeth, put on a light coat, then left the house and started her walk to work. She would work harder, she told herself as she marched forward. She would not allow destructive thoughts into her head any more. She would be a better person. She would follow the City’s rules, even if she found them restrictive. She would follow them

because

she found them restrictive, because she had to fight the evil within her, had to rid herself of it once and for all. Because the City was all that stood between her and self-destruction; between their fragile society and the darkness that longed to destroy it and everyone within it.

The City was where Evie lived, where everyone lived – everyone who was good, anyway. Its high walls protected them from the Evils who scavenged outside, who wanted to kill them all and fill the world with terror, just as they had before.

It had been Evils, or their ancestors, who had nearly destroyed the world some years earlier. Evils who had brought about the Horrors. Before the City, the world had been filled with Evils, humans with no capacity for love, for good. Humans were not all destined to be evil; only a few had distorted brains that made them unfeeling, selfish, bent on destruction. But others were easily influenced, and the psychopaths were convincing, twisting minds, making good people do terrible things and thinking that they were good.

The Horrors had started as a small war, but they turned into a huge one that went on for years. Millions of people died in terrible ways, all because people couldn’t agree with each other. But the one good thing about the Horrors was what had come out of them: the City. Like a phoenix, the Great Leader said in his Sentiments. Outside the City walls, evil still reigned and men still fought with each other for everything – for food, for shelter. There was no order and no civilisation. There was no peace.