The Kitchen Readings (2 page)

Read The Kitchen Readings Online

Authors: Michael Cleverly

The kitchen in Hunter's cabin at Owl Farm was a simple knotty-pine affair, both the walls and the cabinets. A few years ago the pine cabinets were replaced with cherry, but the walls remained knotty pine, with vintage orange shellac. Hunter's famous counter stretched across two thirds of the kitchen. Behind the counter sat Hunter, and behind Hunter were the range, the sink, countertop, and assorted cutting boards. Cooking on the range essentially put you back to back with Hunter, a dubious honor or a dangerous position, depending on his mood. The couch was backed up against the front of the counter so everyone was facing the same direction: the TV. The only other stool at the counter, besides Hunter's, was just to Hunter's left. That stool was always occupied by the person highest in Hunter's pecking order, the sheriff, if he was in attendance. The regulars knew to vacate it when a higher-ranking crony entered the kitchen; newcomers had to be told. Next to that stool was an exercise bicycle. Ostensibly it was there so Hunter could just hop on and get a bunch of exercise, Hunter not being one to go charging off to the gym. It must be reported that Hunter had been seen on the thing, but exercise isn't the word to describe what he was doing. We old-timers weren't too fond of it, but younger guests thought it was pretty cool and would cheerfully jump on and pedal away. There was one easy chair that also faced the TV. Next to the television was the upright piano; in all those years, no one seems to remember ever having heard one note out of it. When Hunter was working on a major project he'd have a large corkboard hung in front of the piano, which would fill up with notes for the book, as well as random aphorisms and bits of pornography. The kitchen would morph

to meet the requirements of the event at hand, with more furniture being hauled in so the maximum number of people could be jammed in to watch the Kentucky Derby, Super Bowl, or perhaps presidential debates.

The living room was through the door next to the piano. It was a nice large room, especially considering Hunter's cabin wasn't particularly huge. A big fieldstone fireplace dominated one end. The wall to the right, as you entered from the kitchen, had the front door and picture windows looking out on the deck and the peacock cage. The room was full of books, plus stuffed animals, skulls, and the sort of exotic memorabilia that people associate with Hunter S. Thompson.

Election Night was always huge at Owl Farm. Some ended well. Some not so well. I think Hunter just kept the pool money from the 2000 election that took so long to resolve.

An old friend, who goes way back with Hunter, explained why that big comfortable room wasn't the center of activity at Owl Farm. It started years ago, when Hunter was between girlfriends and couldn't afford someone to keep house for him. Everyone used to hang out in the living room, but it got to a point where no one had cleaned it up for weeks, maybe months, and it had devolved into an utterly squalid, fetid, pigsty. There were decaying turkey carcasses, which were convenient to snack on for the first few days but started to smell like corpses after a while. Half-eaten ham sandwiches lying around that you'd remember as having been in the same place on

your last visit, and all the other general trash and debris of daily living. Hunter didn't have a very good sense of smell; maybe he was just oblivious to all of it. Ultimately it was easier to just move to the kitchen than it would have been to tackle that god-awful mess. Once the scene moved into the kitchen, it never moved back.

For the big Kentucky Derby and Super Bowl parties, the TV from Hunter's bedroom would be hauled into the living room. The buffet would be set up in there, and that's where the overflow would watch the game. Those of us who spent as much time in Doc's kitchen as we did our own homes would often opt for the living room, as the kitchen would fill up with acolytes and first-timers desperate to be close to him.

Usually the people assembled at Owl Farm fit quite comfortably into the kitchen. When things became uncomfortable there, it wasn't due to overcrowding; that would have been too simple. It was because

someone

was making things uncomfortable. It was something Hunter was very good at.

The good folk of Woody Creek were proud of the fact that Hunter Thompson called their little village home. Woody Creekers are famous for having a set of values different than those of the people up the road in Aspen, and they go out of their way to demonstrate it every chance they get. They embraced Hunter, and he was a good neighbor. He didn't care if you were of the same political stripe as he was, or if you shared his hobbies or leisure-time activities; being a neighbor was different from being a crony; a neighbor was a neighbor no matter what. That feeling was reciprocated. People who were political opposites of Hunter, who would never have joined us in the kitchen for a game or other dubious behavior, felt very warm toward him because they knew he truly was a good neighbor who was cordial and courteous and could be counted on if he were needed.

Hunter felt safe in Woody Creek. Those around him always respected his privacy and would insulate him from outsiders who might try to intrude. You could never get directions to Owl Farm from a Tavern bartender. If a pilgrim set on meeting Hunter seemed overly persistent, a call would be made and someone, such as Cleverly, would appear to do the screening. It would be explained to the individual that he hadn't been asked to come to Woody Creek, and that the thousands of miles that he might have traveled to worship at the altar of “gonzo” were irrelevant. Doc wasn't interested. If a reasonable chat didn't work, there was always the Sheriff.

No matter how exotic or glamorous Hunter's journeys, he always looked forward to his return to Owl Farm, Woody Creek, and the company of his small circle of trusted friends. These are their stories. These tales aren't necessarily the outrageous “gonzo” stuff that people tend to write, and that fans expect to read, about Hunter. Often funny, sometimes poignant, these stories are the real Hunter, the private Hunter. Hunter was a gentleman; he would always rise when a woman entered the room and would always greet someone new with courtesy and decorum. Hunter was a well-bred Southerner with good manners, and that was important to him. When, upon occasion, those manners weren't apparent, it wasn't because he'd forgotten them. He could also be the madman his fans envisioned, the one portrayed in film and in Ralph Steadman's brilliant illustrations. He was also a friend, a husband, and a father.

We're writing this book to show the many sides of Hunterâthe Hunter Thompson who was unavailable to anyone but those closest to him. Even if other writers thought that these were qualities of Doc's they wanted to explore, they couldn't have; they wouldn't have had the access, and now never will.

CLEVERLY DISCUSSES COCAINE AND TITS AS BIG AS TEXAS

It's funny that I don't remember the first time I met Hunter. I had read

Hell's Angels

and

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

before moving to Aspen, so I was well aware of who Hunter Thompson was. I remember seeing him on his stool at the end of the Jerome Bar. But for all that, I can't remember our first real encounter. Maybe I can blame this memory lapse on the seventies; maybe someone was on something. It's likely we were introduced by our mutual friend Tom Benton. Tom is the artist who designed Hunter's

GONZO

fist logo and also the original cover for

Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail,

the one with the stars-and-stripes skull. Tom worked on Hunter's sheriff's campaign

and created the “Aspen Wall Posters,” which were a large part of the PR blitz for that campaign. Tom and Hunter were very good friends and had a mutual respect. As it turned out, Tom and I spent a lot of the seventies and eighties driving the same galleries out of business. It was hard work; we became close. It's likely that at some point he was the one who first put Hunter and me together.

My first real recollection, my first Hunter story, was an encounter that took place at the far end of the Jerome Bar in the mid-1970s. Hunter was perched on his stool; I was on the stool next to him. By now we had become friendly. Friendly enough to share drinks, conversation, whatever else. We were doing just that when a young couple approached with caution. Hippies. I thought I'd left you guys back in Vermont.

It was mid-afternoon on a beautiful sunny day. It was far too nice out for good people to be in a saloon. So it was just Hunter, me, the bartender, a couple of real estate agents scheming in a distant corner, and the hippies. The guy was a furry little fellow, standard hippie-issue fare. The girl was hot. She had great Texas-size breasts swelling out against her hippie top, which did a terrible job of covering them, cleavage to the wind. Hunter chose not to ignore them, the hippies, for two obvious reasons.

“Hi,” the hippies said. It turned out that they were on a pilgrimage, and Hunter was it. They had traveled some distance to meet the great man, and now they were here. And here he was.

“Hi,” Hunter responded. “No, no, not disturbing us at all, just having a little lunch,” he said, eyes glued on Texas.

Hippie ears were cocked, trying to figure what the hell Hunter was saying. This was a classic response for those chatting with Doc for the first time. Or the thousandth. There was plenty of adoration to go around, and Hunter graciously accepted every

ounce of it. He even went so far as to show some interest in them, while mentally willing those young breasts closer and closer to him. He had somehow maneuvered the hippie girl between us and now had his arm around her. I was enjoying her smell. The target area was pointed directly at Doc.

Suddenly the guy edged very close. “Hey,” he whispered, “you guys want a bump?”

Only one answer to that question.

“Where do we go?” the hippie asked.

“Right here's fine,” Hunter said.

It was the seventies in Aspen. We thought the stuff was legal; we thought it was good for you. None of our friends had been hauled off to rehab yet. Hippie boy produced a vial, chock full. Yum, yum. Hunter reached out and snatched it from his hand like a striking cobra. Lightning fast.

He unscrewed the top and held it up to the light, then proceeded to dump out a large pile of cocaine onto the top of each of the young lady's breasts. Both hippies were frozen, mouths agape. I watched, waiting for Hunter to produce a bill to roll up, or some other cocaine-snorting device. None was forthcoming. Hunter proceeded to place a finger over one nostril and bury his face into one of the breasts, making loud snarfling sounds with liberal flashes of tongue. The pile of cocaine disappeared. He repeated the process, covering the other nostril and snarfling the other breast. When he pulled his face away from the girl's bosom, his nose and upper lip were smeared with the white powder. Saliva glistened around his mouth.

He held the vial up to the light again: about a quarter full. He handed it to me. I dumped the remainder of the substance onto the back of my hand and snorted it the same way Hunter had, but unfortunately sans breast. My pulse quickened and there was

a pleasant sensation, though I still was pretty sure that Hunter had had the most fun.

I handed the vial back to Hunter. He held it up again, empty. He screwed the top back on and tossed it to the hippie boy. The hippies stared, mouths hanging open, the girl's cleavage soaked with Hunter's spit. What had just happened?

Hunter turned to me, his back to the hippies, and resumed our conversation at exactly the point where the young couple had interrupted it. They lingered; they had only Hunters back. Then the boy took the girl's arm, and they slowly retreated. Backing up, then turning to the door. They had met Hunter S. Thompson. Did we get their names? Did they get mine? Did we know where they were going, where they came from? They were gone, perhaps off on their next quest.

BRAUDIS REMEMBERS ROUGH AND TUMBLE: PAVEMENT AND POLITICS

My earliest memories are of pavement. South Boston, 1948. Concrete sidewalks and tar streets. Blacktop playgrounds. In the winter people scattered ashes from their coal furnaces on the ice so they wouldn't slip. I remember one cold day being pulled on a sled by my mother. I remember the metal runners screeching over the ash and clinkers. I was bundled in a hooded snowsuit with one ear sticking out. My mother took a shortcut across a vacant lot and a twig got stuck in my eye. As I cried I saw my mother's guilt.

Today, as I gaze out the window at the Elk Mountain range, there is no tar in sight. I came here to ski. Back in Boston, we played hockey on a frozen pond at Farragut Park. Shin guards were copies of the

Boston Globe

friction-taped to my legs. I was a good skater and a good fighter. When I first tried skiing in Vermont I was a natural.

I outgrew the gangs and the juvenile crime. I briefly believed in our government. I married and sired two daughters. I copped a corporate job and thought I was happy. We owned a Ford Country Squire station wagon and a VW bug.

Wasn't this the life everyone wanted? Maybe, but I had this coppery taste in my mouth because of the war in Vietnam.

Instead of baiting cops for sport in Southie, I was shedding the three-piece pinstripes on weekends and getting tear-gassed in antiwar demonstrations. The seeds of rebellion from Boston bloomed in New York. Dope replaced Beefeater, Levi Strauss supplanted Brooks Brothers, and my rail out of the East was greased. I arrived in Colorado to ski. No purpose was the new purpose. Tell me not to do it and I'll do it. Good Jesuit gone awry.

The Teutonic establishment in Aspen was postwar Swiss and Austrian. Never German by admission. We were the newcomers, the outsiders, postgrad hippies and a threat to the status quo and the bottom line. Our growing ranks might hurt real estate values. We thought we could save the Rocky Mountains from those who saw only the bottom line.

Young Braudis, as a rookie, taking advantage of Aspen's social scene.

I had seen Hunter at the bar in the Hotel Jerome. I had read about his battles against the city council and the municipal court. His group was a loose alliance

of artists, lawyers, writers, and shady imports with no visible means of support. They had their end of the long bar.

My bunch skied every day and self-medicated with whatever was handy. We all converged at the Jerome. Without any clear introduction, Hunter and I started calling each other by name. Osmosis by whiskey. Eight nights a week.

Jesus! It seems as though everyone who knew Hunter met him at the Jerome. Its high ceiling, tile floor, and grand Victorian back bar made it a great place to drink. As the sides were forming in the Battle of Aspen, the office of sheriff was Hunter's choice for his first beachhead. In the United States of America the office of sheriff is the only chief law enforcement position controlled by the voters.

That spring the snow was melting, the lifts were closed, jobs had ended, and relationships were difficult. As frozen horse shit thawed, not a tourist was to be found. The climate for conversation was good, and I found my stool was getting closer to Hunter's. I listened to Doc and his brain trust formulate a plan. Hunter saw the opportunity. Power resided with the people. Freaks were people, and more of us arrived every day. If we registered and if we voted, we just might outnumber the complacent conservatives in November. “Freak power” was the surge, and HST had the courage to ride that wave.

Hunter had crafted a platform that might have seemed an odd match for the office he was seeking. He spoke to land use, zoning, and greed control. The sheriff in Hunter's model would become an ombudsman. He declared that as sheriff of Pitkin County, he would change the name of the city of Aspen to “Fat City.” Everything he said that summer appealed to me. I enlisted as a foot soldier in my first real crusade. I understood guns and badges, but what the hell did growth control have to do with

a sheriff? Hunter knew the answer to that question. He was a highly evolved student of essential political matters. In 1958, in

The Rum Diary,

he described the threat posed by greedy land developers by stating that, unchecked, they “spread like piss puddles in a parking lot.” At age twenty-one, he grasped the reality that it was always greed versus the environment.

Bob's campaigns have been consistently more successful than Hunter's.

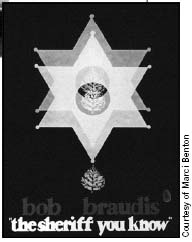

The brilliant artist Tom Benton designed posters for both Hunter and Braudis. Both are much-sought-after collectibles.

What might have appeared to an outsider in 1970 as Thompson's brainless rant against the machine was actually his refined statement about the art of controlling one's environment. That year Hunter already had the powerful magnetism that lasted

until his death. As the nucleus for an embryonic political force that shook Aspen's establishment, Hunter infected a small group of future candidates with a fever that eventually led to victories that we shared with him.

For most of us, that campaign, filled with passion and some tears, was the political apogee. But the friendships and loyalties that Hunter cemented gave some tractionânot unlike those ashes on the ice in my old 'hoodâto subsequent campaigns that gave life to the original agenda that the Doc connected to the concept called quality of life.

Following his loss in November, I remember Hunter asking me about the informal power-up model of gang structure. It was as if he were taking mental notes. I had gone from dean's list to dropout; but now Hunter told me that his foray into politics had exposed weaknesses in the comfortable oligarchy of Aspen. I was starting to feel my part in what Hunter foresaw. Despite the “Carpe Noctum” existentialism and the denial of death and tomorrow, Hunter persuaded me and other supporters to view his loss on Election Day as the beginning, not the end, of “Freak Power.”

The curtain was rising on the Gonzo Years, the hyperbole and craziness, but the pendulum was creeping toward its position of natural repose, with the Doc's hand in touch. He was to become, for me, a polestar and a conscience. Thirty-five years later he was a sharp twig in my eye.