The Kitchen Readings (5 page)

Read The Kitchen Readings Online

Authors: Michael Cleverly

If Thomas Edison had not invented the lightbulb, someone else would have gotten around to it eventually. The same goes for many of our finest inventions. But only Hunter could have invented shotgun golf. Only Hunter, with the physique and hand-eye coordination of a natural athlete, would have found the similarities between golf and skeet shooting so obvious. There were many things about Hunter that the country club golfing crowd didn't approve of, but the sight of the butt of a twelve-gauge sticking out of his golf bag filled them with a kind of unease they could scarcely comprehend.

It was midsummer in the late eighties. Hunter had received a set of Ping beryllium golf clubs, hand-me-downs from his

brother. A few years earlier these clubs had been considered a breakthrough in sports technology. Made from a hard metallic element commonly used in atomic reactors, the irons were widely believed to enhance the scores of the weekend golfer. Hunter had never swung them.

Hunter had created a one-hole golf course in the meadow at Owl Farm that doubled as a firearms range. The “green” was a twelve-by-twelve square of linoleum salvaged from one of his domestic remodels and placed on the grass about a hundred yards from the house. The pin was a unfurled beach umbrella stabbed through the center of the linoleum and into the soft earth. The “pin” provided a target and a crude range finder. The golf clubs were still in their bag and secured by a blanket that had been duct-taped over the club heads, forming an improvised traveling bag for the clubs. This same bag had flown from Aspen to Phoenix the winter before for the previously mentioned and aborted golf vacation, when Hunter was officially on assignment for the

San Francisco Examiner

to cover the impeachment hearings for Evan Mecham.

Back in Woody Creek, I stripped the duct tape and blanket from the golf bag and pulled out the nine iron and pitching wedge. At Hunter's request, I had brought a couple hundred used golf balls. Hunter started swinging at balls in order the hit the “green.” None of his shots came close. Frustrated, he asked me to try. After flying balls over the linoleum with the nine iron, I picked up the wedge and “Plop,” my first shot landed audibly on the square. I repeated the lofting shots a few times with persistent accuracy.

Hunter tried a few shots with the wedge and got more frustrated. He was stiff and rusty. Modern golf technology couldn't help his swing. Unwilling to waste a beautiful summer after

noon, Hunter suggested that I hit the high wedges while he tried to shoot them in mid-flight with a double-barreled side-by-side twelve-gauge shotgun.

We arranged his firing position to pose no danger to the golfer or the yuppie mountain bikers from Arkansas, as he referred to them, pedaling along the road past Owl Farm.

I would pop a high arching ball toward the pin, and Hunter would shoot. After six or seven attempts to hit the ball, and with no obvious deviation in its flight, Hunter replaced the light 7 1/2 shot with a heavier and larger number-four shot. The results didn't change.

Hunter was nearing that level of disappointment that I recognized as the onset of a temper tantrum, which would lead me to go home while his temper continued into his future activities that evening, so I suggested that the mass of the ball, its surface, speed, size, and trajectory, might have something to do with the appearance that Hunter's aim could be in the same category as his golf swing. My proposed experiment involved somehow suspending a golf ball in the air and having Hunter shoot at it from a distance similar to the range between him and the earlier balls while they were in flight.

Hunter with his favorite club in the bagâ¦twelve-gauge.

Hunter went into the house and came out with a roll of cellophane tape and a peacock plume. He taped a golf ball to one end

of the plume and taped the other end of the plume to a willow bush. Standing about twenty yards from the target, he loaded the shotgun, aimed, and fired. No movement of the golf ball. He raised the weapon, took aim, fired, and got the same results. We approached the ball and found evidence of lead transfer on the white jacket of the Titlist.

Our conclusion was that the triggerman may have been hitting the moving targets but did not have any effect on the balls' flight path. “Hot damn!” shouted HST.

Shotgun golf died a natural death. It was reincarnated about twenty-five years later in Hunter's column at ESPN.com. His new version was replete with rules, and of course the match could be wagered on. It was reprinted in Hunter's book

Hey, Rube.

I doubt anyone else will attempt a match outside their imaginations.

A potential caddy at the

Hey, Rube

book signing that Walter Issacson threw at the Aspen Institute.

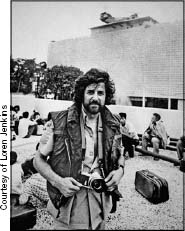

Loren Jenkins was one of Hunter's friends from his earliest days in Aspen. Jenkins was Saigon bureau chief for

Newsweek

magazine during the Vietnam War, and later was Rome bureau chief for the

Washington Post.

He won a Pulitzer Prize for his work in Lebanon and is now senior foreign editor for National Public Radio. He and his wife, Missie Thorne, now live in D.C. but maintain a home in Old Snowmass, just down the road from Aspen. When in town, Loren was a fixture in the kitchen, being good friends with all the regulars, including Ed Bradley, whom he was close to in Vietnam. Loren was the first person Hunter called when

Rolling Stone

sent him to 'Nam, and the two hooked up again when they covered the U.S. invasion of Grenada.

Prior to their move to Old Snowmass, Loren and Missie lived on McLain Flats Road. McLain Flats is the back way to Woody Creek from Aspen. Sometimes, returning from town late at night, it was a good idea to take the back way. If one suspected the headlights in the rearview mirror of belonging to a peace officer, one could pop in and pay Loren and Missie a visit. Hunter was an occasional visitor.

Hunter's drop-ins would usually be the product of paranoia, and would always be very late, after the bars closed. Loren and Missie found this more amusing than annoying. Hunter would barge in whether they were in bed or awake, and the three of them would sit around and shoot the shit until Hunter thought the “danger” had passed. Occasionally Hunter's hosts would be out for the evening. This wouldn't deter him; he'd still have to hide out till the “heat was off,” so he'd let himself in and occupy himself by relocating small household objects. When Loren and Missie returned home, they'd be vaguely disorientated: things wouldn't be quite the same, and eventually they'd decide that Hunter had been there. When Loren and Missie moved to Old Snowmass, a few miles down valley, they sold the McLain Flats house to a young professional couple. The couple was just starting a family; both were attorneys. But the fact that Hunter's friends no longer lived there, that the house had changed hands, didn't deter him at all. The new owners would find him hanging out in their living room, lying low, at all hours. Jenkins explained that Doc went with the house.

'NAM: HUNTER ARRIVES

In January 1975, Vietnam began to come apart. Loren Jenkins was in Nepal working for

Newsweek.

When the shit hit the fan, he was transferred to Saigon. On April 28, 1975, Saigon fell, and it was over. When things went south, they went south fast.

In early February of that year the provincial capital Boun Me Thuot was overrun, and at that point it was clear to all that the end was near. A month later Hunter called Loren and said he had a job covering the war and wanted to know what it was like over there. Loren illuminated him: “It was what it was, the end of a war.” Hoping for some more useful details, Hunter then called Loren's first wife, Nancy, who was in Hong Kong. After a lengthy conversation, he concluded that it was what it was.

In late March, Hunter flew from Aspen to Hong Kong. He allowed himself three days in Hong Kong to buy “equipment” before heading to Saigon. During that time, Loren called him and asked that he stop by the

Newsweek

bureau and pick up some cash. Loren had a staff of fifteen: five Western correspondents and the rest locals. They had to be paid, and there were operating expenses. No one was taking checks at that point. Loren wanted Hunter to grab forty thousand dollars in cash. He said, “Don't put it in your bag. You have to tape it to your body.”

When Hunter got off the plane in Saigon he was perspiring heavily. The shock of the tropical heat after the air-conditioned airplane messed with his chemistry. He was dressed exactly like Hunter S. Thompson: Aloha shirt, Bermudas, tennis sneakers. While this was acceptable vacation wear back in the States, it wasn't exactly normal in Saigon at the end of an ugly war. It was also terrible camouflage for someone smuggling forty thousand dollars in U.S. currency. Hunter spotted a sign declaring

ANYONE CARRYING OVER

$100

IN CASH WILL FACE PROSECUTION

. This produced an entirely different kind of sweat. Hunter was sure that he could smell the difference, and that everyone else could, too. Even the finest duct tape wasn't designed to hold up against this sort of nervous perspiration. He became displeased with his friend Loren Jenkins. He became edgy. But he persevered.

There were two hotels in Saigon preferred by the foreign press, the Caravel, a slick modern edifice where the TV types stayed, and the Continental Palace, a fine old colonial building, the hotel of Graham Greene, where the print journalists holed up. When Loren returned to the Palace that afternoon the manager rushed up to him. “There was an American here looking for youâ¦. I think he's CIA.” Loren asked what made him think that. The manager's reply suggested that the fellow's odd dress and strange behavior could only be explained as that of an inept American spy. “He wanted a room. I told him we had none. I can find him one if you like.” Loren told the manager that he was pretty sure he knew who the gentleman was, that he wasn't a spy, and that, yes, he should be given a room. He then headed to the bar. Shortly thereafter he was confronting a fairly agitated Hunter Thompson. “I've been ripped off.” Loren felt dizzy, assuming the worst. “My forty thousand!”

After being turned away from the Continental Palace, Hunter's keen instincts had somehow led him straight to Tu Do Street, the center of sin and vice in Saigon. The district was clogged with prostitutes, beggars, and grifters of every shape and form. There was a thriving black-market business exchanging U.S. dollars for piastras. There was also a common scam involving that business.

The black marketeer would offer the “mark” a good exchange rate, usually on a hundred dollars, and as he was handing the gringo a roll of Vietnamese currency, he would look over the mark's shoulder and say the Saigon equivalent of “Cheese it, the cops! Split up. You go that way!” The two would take off in opposite directions, and when the mark stopped running and stepped into a bar or restaurant to count his money he'd find one small denomination note wrapped around a roll of paper. This is

what had happened to Hunter. Loren was profoundly relieved: a hundred dollars of Hunter's own money was an acceptable loss.

Loren's relief was short-lived, as Hunter immediately launched into a rant about the awkwardness at the airport, which he perceived as a setup and betrayal. In a brilliant flanking action, Loren interrupted and mentioned that he'd procured a room for Hunter, but that the manager thought he was with the CIA. This insult bored directly into Hunter's dark heart, and as he started sputtering about the great pride he felt at being on Richard Nixon's enemies list, the little “thing” at the airport was instantly forgotten. There had been no incident at customs anyway. Hunter felt that his press credentials had gotten him through; Loren secretly thought that the authorities probably figured that no real smuggler would ever be that obvious.

Loren got Hunter checked into a room and they agreed to meet an hour later. The Continental Palace had a lovely courtyard, bar, and restaurant on the ground floor. Because of the 9:00

P.M

. curfew in Saigon, this was where the press corps spent their evenings. The journalists would file their stories from their rooms, do whatever they had to do on the streets, and be back in the bar by nine. Hunter and Loren met in the courtyard, and Loren introduced Hunter around to the assembled press, about half of whom were pretty excited to meet him.

There was also a Mr. Chu, well known at the hotel but not a member of the press corps. Mr. Chu and his Samsonite case would turn up at the hotel sometime around the dinner hour. Several journalists, Chu, and the case would often retire to one of the reporters' rooms. In the case were pipes, lamps, and opium. Opium was the drug of choice in Southeast Asia. Graham Greene favored it. A subtle, old-school drug, opium is usually associated with peaceful ruminating, a clear head, and perfect recall the

following day. Hunter Thompson was invited upstairs with the fellas. Later Loren Jenkins was told that Hunter had two or three pipes, a large dose.

The gang returned downstairs, and Loren joined them for dinner. It was a fairly large group. Well into the meal, Hunter excused himself and headed to the men's room. The doors to the bathrooms were separated from the dining room by only a large bamboo screen, which Hunter disappeared behind. Minutes later blood-curdling screams were heard coming from that direction. Every head in the dining room snapped around. “LOREN, LOREN, HELP!”

As Loren sprang to his feet, Hunter came crashing through the screen, sprawling onto the dining room floor. He was hyper-ventilating, panicked; they almost called a doctor. Hunter's drug Achilles' heel had been discovered. The next day he admitted to Jenkins that he had actually done opium once before, with the same effect. You'd think he would have remembered that beforehand.

'NAM: SAIGON FALLS

The North Vietnamese Army was pushing south. Quang Tri fell, then Hue. The conversation in the courtyard of the Continental Palace centered on what the journalists would do when the North Vietnamese got to Saigon. Bug out? Stay and report? Stay and fight? There were many loony scenarios. Some of the macho types thought they should arm themselves. Jenkins and the old hands felt this was a lousy idea; their neutrality was their only real defense. The gung ho cowboys were asked to find a new place to live.

At this point Hunter had been in Saigon for four or five days, and he announced that he was going to Hong Kong. Loren was

incredulous: “You're here to write

Fear and Loathing in Saigon,

not Hong Kong.” Loren was deeply disappointed, Saigon was as crazy as a place can get, and being a great admirer of Hunter's writing, he truly felt that Doc was the perfect person to report it. Hunter insisted that the trip was absolutely necessary, claiming that

Rolling Stone

editor Jann Wenner had canceled his insurance before he had left the States and that he had to get that situation cleared up before he faced any more unreasonable danger. Once again Loren was incredulous. It seemed that Hunter only liked danger when he was the most dangerous person in the room. The situation in Saigon was far beyond Hunter's, or anyone's, control; it was an entirely different sort of danger. In any case, Hunter spent six days in Hong Kong and then returned to Saigon. Loren was pleased to see him but mildly concerned about the huge footlocker he was traveling with. Anything could be in it.

It turned out that Hunter had decided to organize the press corps. The footlocker was full of high-tech equipment: tape recorders, walkie-talkies and all manner of sneaky electronic devices. He wanted to wire everyone; there were code words and passwords. The international press corps, jaded war correspondents, were about as cynical as you could get. They had no idea what to make of Doc's efforts.

All this time, he hadn't written a word. Since this certainly wasn't Hunter's first rodeo, he knew how to hedge his bets, so he had a large top-of-the-line reel-to-reel tape recorder and was recording everything as events unfolded, in case he ever did decide to write. When Loren got a 3:00

A.M

. phone call from the New York office (post three-martini lunch, New York time), Hunter was there recording. When Loren patiently explained that, no, he couldn't get a photo of the presidential palace with a

tank in front of it and a hot chick standing in front of the tank, because there were no tanks or hot chicks in front of the palace, and because he didn't stage photographs, Hunter got it. When Hunter was out in the field listening to a speech given by an American colonel to his troops indicating that they were going to fight to the last man, Hunter got the speechâand, in the background, the sound of a chopper as it approached, landed, and swept the colonel off to safety. This was good stuff.

One week before the fall of Saigon, Hunter announced, “I gotta fly to Laos.” Loren, again, couldn't believe it. This was it, the big show, surely the most significant event in Hunter's journalistic career. Saigon was where the story was. Hunter was adamant. “I have to watch this thing from Laos.” He flew to the sleepy town of Ban Dien and stayed there as Saigon fell. As near as Jenkins can remember, the only writing Hunter ever published on the fall of Saigon was a cable he shot off to Jann Wenner bitching about the insurance situation and asking for more expense money.

The night before Hunter left for Laos, he and Loren were chatting about what would happen next. The only “next” that Loren was interested in was his own, not Vietnam's. He told Hunter about a little thatched hotel on a beach on the island of Bali. That was his “next.”

Loren had told the American ambassador to Vietnam that he wasn't leaving the country until the ambassador did, so he was on one of the last choppers out of the embassy compound. From there, he flew to an aircraft carrier, where he spent four days as it steamed to Subic Bay. During his time at sea he filed his final dispatches on the fall of Saigon and the end of the United States' Vietnam adventure. Loren's editors told him to take as much time off as he wanted, and he soon

found himself in a bungalow on the beach at the hotel Tan Jun Sari on Bali.