The Knight in History (10 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

Whereas so much of the terminology of medieval history and criticism is the invention of the eighteenth century, the terminology of troubadour poetry is wholly contemporary. The worldly, witty, and self-conscious verse was discussed and evaluated by its practitioners and their circles. Poets wrote verses criticizing and satirizing each other and theorizing about their own poetry. Literary controversy developed, with songs exchanged like challenges. Should poetry be clear and accessible, easy to understand, and social in nature

(trobarleu)

, as in the verses of Bernart de Ventadorn and Raimon de Miraval, or should it be personal, allusive, and difficult, making use of colored words with overtones and nuances, like the poetry of Arnaut Daniel

(trobar clus)?

Marcabru boasted that he had written poems he himself could not understand. Should it be rough

(trobar braus)

, with discordant, harsh words, or smooth

(trobar plan)

, or delicate

(trobar prim)?

Typically the songs were in stanza form, with usually seven or eight metrically identical strophes and a

tornada

, an envoi of two to four lines. Each poem had a different rhyme scheme and meter; some rhyme schemes were very complicated.

TROUBADOUR BOUND WITH A GOLDEN THREAD OF LOVE, FROM THE FOURTEENTH-CENTURY MANESSE CODEX, A COLLECTION OF MINNESINGER VERSE.

(UNIVERSITÄTSBIBLIOTHEK HEIDELBERG, COD. PAL. GERM. 848, F. 251)

COURTLY LOVE:

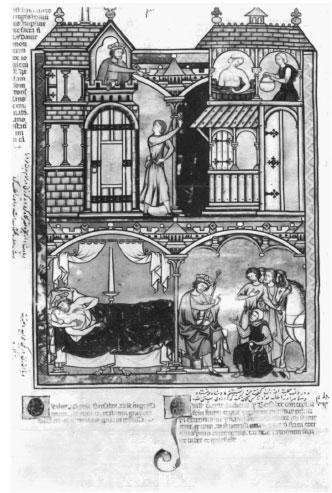

DAVID AND BATHSHEBA, FROM THE ILLUMINATED BOOK OF THE OLD TESTAMENT.

(PIERPONT MORGAN LIBRARY, MS. 638, F. 41V)

The product of poets who were original and individual, troubadour poetry derives its distinctive unity from its very nearly unanimous subject matter: love as a means of a man’s self-realization. What kind of love best achieved this end? The troubadours examined love in all its permutations, analyzed it, weighed it: physical love, in the setting of the court, with its manners and customs; the dreamlike love for a distant and unapproachable lady realized only in the imagination; love on a transcendental plane, for God or the Virgin Mary. They defined, in varying terms, good and bad love:

Fin’ Amors

and

Fals’ Amors. Fals’ Amors

was always unbridled lust, but

Fin’ Amors

could be otherworldly, or it could be earthly love controlled by reason and moderation or merely practiced according to the ideas of proper court behavior.

Earthly love had one invariable characteristic: it was adulterous. The object was always a married woman. With equal invariability her status was always higher than that of the poet, who approached her humbly and worshipfully, eager to “serve.” Sometimes she was cruel and deceitful, sometimes kind, sometimes she remained unattainable. In the background of this two-character drama, played over and over in troubadour verse, hovered a pair of minor but essential elements, the jealous husband and the

lauzengier

, the throng of gossiping, cynical, malicious scandalmongers.

This “courtly love,” to use the label invented by a nineteenth-century critic, has provoked more comment than almost any other aspect of medieval civilization. Gaston Paris, who coined the term in 1883

21

and whose views were accepted for many decades, deduced from the poetry an aristocracy that legitimized adultery and practiced it as an art. The game had a system of rules codified at the court of the counts of Champagne by Andreas Capellanus (André the Chaplain) in a work called

De arte honeste amandi (On the Art of Noble Love)

, written in the 1190s. Paris accepted as realistic Andreas’s picture of twelfth-century ladies and poet-knights entertaining themselves with mock trials at which varieties of amatory conduct were argued and judged and love was found to exist only “outside the bonds of wedlock,” and at which decisions were pronounced on all the minutiae of adulterous love.

22

Today, however, these “courts of love” are generally regarded as fiction, and Andreas’s intention is perceived as satirical.

23

The “courtly love” of the troubadours is regarded by most scholars as having been either artificial convention or tongue-in-cheek wit. Sexual freedom, particularly before marriage, was an explicit medieval male prerogative. A twelfth-century nobleman of northern France was described by a chronicler intent on flattery as surpassing in his sexual exploits “David, Solomon, and even Jupiter” his funeral was attended by ten legitimate and twenty-three illegitimate children.

24

No such freedom was accorded women. Adultery on the part of a wife cost a husband his honor and was therefore punished by disgrace or repudiation, with the lover often killed or castrated. Adultery with the lord’s wife was the worst crime a vassal could commit. Yet this was precisely the aim expressed over and over by the troubadours, whose verses, far from being passed surreptitiously from lover to lady, were sung aloud in public.

The theme is so persistent and freighted with such emotional conviction that it seems as if some real motivation must lie behind it. It has been suggested that the married woman of higher rank was “a conduit of status” for the knightly poet.

25

A countess or chatelaine offered the “poor knight” an opportunity, in his own reiterated words, to enhance his

valors

(worth) and

pretz

(excellence). The troubadours flattered ladies to reach their lords; courtly love was ambitious flirtation.

Georges Duby, in his

Medieval Marriage

and in an essay “Youth in Aristocratic Society,” goes further, asserting that troubadour poetry was an expression not only of the desire for upward mobility but of the frustrations, particularly strong in the twelfth century, that resulted from the knight’s position in society. A knight was considered a “youth” until he had married, become the head of a house, and started a family. Younger sons, or even eldest sons unable to make a good match, might remain “youths” for a long time, even permanently. Although the troubadours glorified youth, the longed-for and often unreachable goal was to join the company of the adults. The poetry of courtly love may have been a gesture of defiance to the system, a “sublimated form of abduction.”

26

The traditional view of critics is that the poetry of the troubadours idealized women. Perhaps the reverse is true: the women in the poems already possessed a status from which the poets, through their verses, sought to borrow. Sometimes pictured as kind and beneficent, sometimes as cruel, capricious, and treacherous, the heroines of the poems always remained objects through which the poet tried to attain his goal of self-realization or, more concretely, position at court.

The ladies associated with the troubadours by the

vidas

and

razos

possessed all the attributes of the subjects of the verses: they were almost always great ladies, and invariably married. Arnaut Daniel was supposed to have fallen in love with “the wife of Lord Guillem de Buovilla.” Gaucelm Faidit “fell in love with Maria de Ventadorn,” lady of the castle of Ventadorn.

27

Guillem de Balaun’s inspiration was “a gentle lady from Gabaudan, Guilhelma de Jaujac,” whom “he greatly loved and served in deeds and songs.”

28

Peire Rogier loved Ermengarde, viscountess of Narbonne, “and made his verses and cansos for her.”

29

Raimbaut de Vaqueiras loved “the [married] sister of Marquis Boniface [of Montferrat],”

30

Richart de Berbezill “a lady, wife of Jaufre de Tonnay, a valiant baron of that area, and the lady was gentle and beautiful and gay and pleasant.”

31

One troubadour, Uc Brunenc, from Rodez, loved “a [presumably wealthy] bourgeoise of Aurillac named Galiana, but she did not love him,” whereupon he became a monk.

32

Raimon de Miraval’s

razos

credit him with seven exploits of gallantry with seven high-born ladies.

33

Some love affairs attributed to the troubadours are demonstrably fictional, as in cases involving historical figures about whom we have external information. Sometimes the biographer patently borrows a story, as in the

razo

of troubadour Guillem de Cabestang, recognizable as “The Eaten Heart,” a favorite folktale whose most famous version is “The Castellan of Coucy”: a knightly lover is slain by his mistress’s husband, who has his heart roasted and served to his unaware wife.

34

The poets themselves were less indiscreet than their biographers. Usually the songs are addressed merely to a nameless “lady.” Sometimes the subject is given a code name: Lady Better-than-Good, More Than a Friend, Best of Ladies, Good Neighbor. When “real” names are given, they are often unidentifiable.

Significantly, the ladies in troubadour songs are a faceless assemblage, with little to distinguish one from another. Eyes are neither blue nor dark but merely “beautiful,” nor is hair color often mentioned. All the ladies display red mouths, white breasts, and slender white bodies, and all are endowed with the prescribed virtues:

pretz, sabers, cortezia, umiltatz

(excellence, wisdom, courtesy, humility).

35

A song by Bertran de Born does explicitly what much troubadour poetry does in effect. Since his lady cares nothing for him, and since he can find no substitute, he will “cull from each a fair trait

To make me a borrowed lady

Till I again find you ready.” From “Bels Cembelins,” her color and eyes. From Aelis of Montfort, “Her straight speech free-running, / That my phantom lack not in cunning.” From the viscountess of Chalais, “Her two hands and her throat.” From Lady Anhes of Rochechouart, her “grace of looks.” From Audiart at Malemort, “her form that’s laced / So cunningly.” From Miel-de-ben (Better Than Good) “Her straight fresh body,

She is so supple and young,

Her robes can but do her wrong.” From Lady Faidita, “Her white teeth.” From Bels Mirals, “Tall stature and gaiety.” Finally,

Ah, Bels Senher, Maent, at last

I ask naught from you,

Save that I have such hunger for

This phantom

As I’ve for you, such flame-lap,

And yet I’d rather

Ask of you than hold another,

Mayhap, right close and kissed.

Ah, lady, why have you cast

Me out, knowing you hold me so fast!

(Translation by Ezra Pound)

36

Eighteen of Arnaut Daniel’s songs have survived, seventeen of them

cansos

.

37

The other is a

sirventes

satirizing, in terms surpassing Guillem IX in their coarseness, the conventions of courtly love which the other songs demonstrate: the Lady Ena seeks to impose a condition on her suitor, Bernart de Cornil, to which, transgressing the code of lovers, he refuses to accede; the whole world of knights and troubadours is torn by the controversy, with some condemning Bernart, others defending him. The lady’s condition, an “unnatural” form of intercourse that shocked Arnaut’s early-twentieth-century editor, is debated—and rejected—in a tour de force of versification: five verses of nine lines each and a four-line

tornada

, each verse with a single rhyme, and the

tornada

continuing the rhyme of the final stanza. At the same time, the song is full of plays on words, including a series of puns on “Cornil,” Bernart’s place of origin.

*

38