The Korean War: A History (13 page)

Read The Korean War: A History Online

Authors: Bruce Cumings

Early war coverage was fascinating and instructive, revealing its essential nature, its

civil

nature; war raged up and down the peninsula for six months, and everything was seen. Then for the last two years it was positional warfare along the DMZ, and Westerners had little contact with Koreans except as enemy, soldier, servant, or prostitute. Thompson was appalled by the ubiquitous, casual racism of Americans, from general to soldier, and their breathtaking ignorance of Korea. Americans used the term “gook” to refer to all Koreans, North and South, but especially North Koreans; “chink” distinguished the Chinese. Decades after the fact, many were still using the term in oral histories.

2

This racist slur developed first in the Philippines, then traveled to the Pacific War, Korea, and Vietnam. Ben Anderson called it a depository for the “nameless sludge” of the enemy, and it might be the namelessness of Koreans, in American eyes, that stood out then and still does today. Donald Knox’s voluminous oral histories, for example, rarely if ever name any Koreans. But American soldiers do comment on the paradox that “their gooks” fought like hell whereas “our gooks” were cowardly, bugged out, never could be relied on. (General Dean sampled the fierce resentment that being called “gook” stirred in all Koreans, North and South.

3

) It did not dawn on most Americans that anticolonial fighters might have something to fight about.

In the summer of 1950 basic knowledge about the KPA and its leaders was treated as a revelation—for example, that the majority of its soldiers had fought in the Chinese civil war. Three months into the war,

The New York Times

found big news in a biography of Defense Minister Choe Yong-gon released by MacArthur’s headquarters: it discovered that he had fought with the Chinese Communists, placing him in Yanan in 1931 (no mean feat, three years before the Long March). Also unearthed was the information that he was in overall command of the KPA, which appeared to suggest that international communism was allowing the locals to run some things. Two days later the

Times

turned up the news that the division commander Mu Chong had also fought in China, and that most of the KPA’s equipment had been sold to it by the Russians in 1948. Ergo,

With its peculiar combination of fanaticism, politics and just plain rudimentary fighting qualities of Orientals … [the KPA] is a strange one. Some observers believe that, in the absence of good pre-war intelligence, we have just begun to learn about it.

4

Early on, the

Times

had found a queer tone in North Korean statements to the United Nations: they “had a certain ring of passion” about them, as if they really believed what they were saying about American imperialism. The

Times

’s own rendering of the “imposter” Kim Il Sung read as follows:

The titular leader of the North Korean puppet regime and ostensible commander of the North Korean armies is Kim Il Sung, a 38-year-old giant from South Korea, where he is wanted as a fugitive from justice. His real name is supposed to be Kim Sung Chu, but he has renamed himself after a legendary Korean revolutionary hero … and many Koreans apparently still believe that it is their “original” hero and not an imposter who rules in North Korea.

5

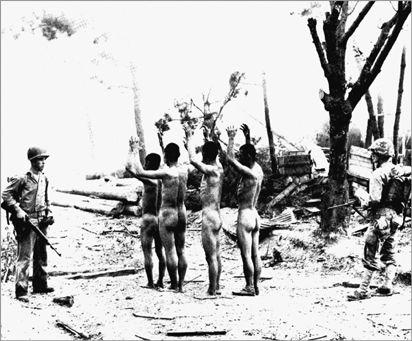

KPA soldiers captured during the Inchon operation.

U.S. National Archives

Somehow the

Times’s

“all the news that’s fit to print” seemed scripted by Syngman Rhee. The ordinary reader would believe that KPA soldiers were trouncing Americans and dying by the thousands, all for a poseur with a hyperactive pituitary, a John Dillinger on the lam from august organs of justice in Seoul.

Thompson’s initial encounter with American racism was the appalling spectacle of MacArthur’s greatest triumph, at Inchon. Why, after their defeat, he asked, were POWs paraded stark naked by the Americans? The dehumanization of “the gooks” was palpable whether in defeat (Taejon) or in victory (Inchon). But this slur “could not rob the slain or the living of their human kinship, nor the naked procession of prisoners, with their hands folded upon their heads—as though they might conceal weapons even in their bodies—of

an uncouth and tragic dignity.” Every other correspondent saw this naked parade of shame (but whose shame?); few of them commented on it. And then it turned out the nude men were young, inexperienced decoys; about two thousand North Koreans defended against seventy thousand UN forces in 270 ships. The actual Korean People’s Army “had disappeared like wraiths into the hills.” MacArthur’s trap “had closed, and it was empty.”

6

Worst of all, in another reporter’s eyes, were the Korean National Police. They ran rackets, procured destitute girls for brothels, blackmailed people by threatening to call them Communists, and executed thousands of political prisoners. In November 1950 an Australian journalist, Alan Dower, witnessed a retinue of hooded women, many with babies, roped together and dragged along by ROK police. He followed them until they were kneeling before “a deep freshly dug pit,” ringed by machine guns. Dower pointed his rifle at the commander and said, “If those machine guns fire I’ll shoot you between the eyes.” And so he saved the women, at least for the moment. American soldiers also witnessed the summary execution of North Korean POWs, almost as a routine. Sometimes GIs turned a captive over to the Korean police, to be shot. Sometimes they just did it themselves. But sometimes they did the right thing. Pfc. Jack Wright witnessed a group of around a hundred civilians, including old men, pregnant women, and children as young as eight, digging their own graves as ROK policemen stood guard, ready to murder all of them. Wright told them to stop; the Korean in charge said he had his orders and planned “to execute these people.” Wright pointed to a machine gun and told him not to move, as other GIs escorted the civilians to safety. “This kind of thing happened all over the front,” he later said (meaning massacres rather than brave interventions).

7

Similar atrocities occurred across Korea as the South recovered its own territory and marched through the North, but that was also the point where courageous and honest journalism came to an abrupt end. World outrage at the South’s atrocities did change U.S. policy: in January 1951 “correspondents were placed under the complete jurisdiction of the army.” Criticism of allies and allied troops was prohibited—“any derogatory comments” met the censor’s black brush. American reporters were the most cowed and therefore, Philip Knightly thought, the most useless; worst of all, some U.S. journalists and editors even concocted false reports. Soon foreign reporters were so sick of UN Command “lies, half-truths and serious distortions” that they found Wilfred Burchett and Alan Winnington, both writing from the enemy side, more informative.

8

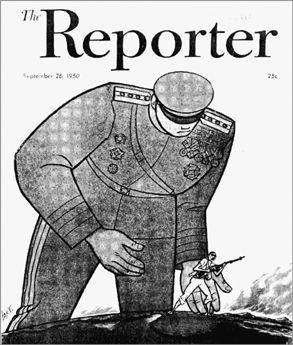

The Reporters

faked article on Soviet puppetry.

Courtesy of the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center

What got past the censors was often killed on the McCarthy-terrorized home front; even Edward R. Murrow’s reports were sometimes dead on arrival at CBS headquarters in New York. The

fiercely independent and eagle-eyed I. F. Stone perused the global print media and wrote a famously contrary book,

The Hidden History of the Korean War;

twenty-eight publishing houses turned it down before Monthly Review Press brought it out in 1952.

9

For many years one of the few good sources on MacArthur’s “my little fascist,” General Willoughby, was a big exposé in

The Reporter

, a magazine that could be found on every liberal’s coffee table in the 1950s. Yet it also ran articles faked by the CIA (one of them a cover story purporting to come from a Soviet defector who helped build up the North Korean army), and its crusading editor, Max Ascoli, had Allen Dulles (then a top aide in the CIA) check the page proofs of two long articles on the China Lobby; elements in the CIA probably informed parts of the articles, which did, indeed, contain much new information.

10

It took more than a decade before Hollywood began to unlock this history in films (and in truth it never did). The singular classic film of the Korean War is

The Manchurian Candidate

, appearing in 1962 only to disappear for decades after it seemed to anticipate Kennedy’s assassination. An odd mix of terror and high camp, its genius was to wrap the Orientalism and Communist-hating of the fifties in the black humor of the sixties, amid the self-congratulatory pillorying of the McCarthy character (presented as a henpecked fool and knave); the film allows one to be chic in one’s prejudices. The battle itself is fleeting, haphazardly staged on a backlot. Yen Lo, the evil Oriental, superbly portrayed by Khigh Dhiegh, became a stunning media signifier for demonic Orientals thereafter. Dhiegh had a long career in similar Hollywood roles (“Wo Fat,” “Four Finger Wu,” “King Chou Lai,” aka Chou En-lai; in his first film,

Time Limit

, he played Colonel Kim, a nasty interrogator of American POWs in Korea), but was otherwise known as Kenneth Dickerson—born in Spring Lake, New Jersey, of Syrian and Egyptian ancestry.

Candidate

is the one Korean War film of lasting significance, but it mostly reinforces stereotypes about Asian Communists and what the war was about.

NSTINCT FOR

R

EPRESSION

As the year 1950 got going, Senator Joseph McCarthy remarked to a reporter, “I’ve got a sock full of shit and I know how to use it.” Soon he rose to denounce 205, or 57, or, as it happened, a handful of vulnerable liberals in the State Department and elsewhere as “Communists and queers who have sold four hundred million Asiatic people into atheistic slavery.”

11

McCarthy exemplified a destructive ideological era when labels stood in place of arguments and evidence made next to no difference. If the same phenomenon can be sampled today on our TV shouting matches, Tailgunner Joe and his allies dramatically wrenched the American political spectrum rightward, interrogating, castigating, and nearly burying the progressive forces of the 1930s. Their bludgeon was an undeniable global crisis detonated by the Soviet atomic bomb and the Chinese revolution, which seemed to spread red ink across half of the globe and jolted Americans, basking in their grand victory in 1945 but still remarkably unworldly, into thinking a handful of internal foreigners—traitors—had caused it all. On the very day McCarthy first rose in the Senate to denounce communism in government, Senator Homer Capehart of Indiana exclaimed, “How much more are we going to have to take? Fuchs and Acheson and Hiss and hydrogen bombs

threatening outside

and New Dealism eating away at the vitals of the nation! In the name of Heaven, is this the best America can do?”

12

For Americans who had to be told what a Communist looked like,

13

McCarthy supplied plausible models: mainly Eastern establishment blue bloods, but also Foggy Bottom scribblers, tweedy professors, closet-bound homosexuals, and China experts who had been abroad too long—anyone who might be identified as an internal foreigner, alien to the American heartland.

(The Freeman

once said that Red propaganda appealed only to “Asian coolies and Harvard professors.”) Almost anybody with a good education might

qualify; thus the bane of the liberal in the fifties was the threat of mistaken identity.

Domestic politics in America is like rugby, slouching toward the goal line, hamstrung by constituents, lobbies, and the pulling-and-hauling of a thousand bargains, lacking autonomy. Foreign policy is like ballet, the long pass from quarterback, or the boxer with a knockout punch. McCarthy was a nihilist who believed in nothing; a breaker of Senate rules, he also broke free of the webs of domestic politics, taking a foreign-policy issue that hardly anyone understood and running with it. Drawing upon an aggrieved mass base, he escaped the slogging politics of Congress to launch ideological attacks on the Truman-Acheson executive, thus constraining the extraordinary autonomy foreign-policy elites had exercised since 1941, and placing distinct outer limits on the spectrum of “responsible” foreign-policy discourse which persist to this day.