The Korean War: A History (17 page)

Read The Korean War: A History Online

Authors: Bruce Cumings

American policy toward Korea was driven by local events in 1945 and 1946, especially the strong left wing in the South that pushed the occupation toward a premature Cold War containment policy. Much of the occupation’s de facto policymaking and its support for the Korean right wing was opposed by the State Department;

in this period southern Korea was a microcosm of policy conflicts and anti-Communist policies that would later mark U.S. policy throughout the Third World, but when containment became the dominant policy in Washington in early 1947 it had the effect of ratifying occupation actions. Internal documents show that South Korea was very nearly included along with Greece and Turkey as a key containment country; although never admitted publicly, in effect it became a classic case of containment in 1948–50, with a military advisory group, a Marshall Plan economic aid contingent, support from the United Nations, and one of the largest embassy operations in the world.

The new Korea policy derived from the Truman Doctrine and the “reverse course” in Japan, which created a new logic of a regional political economy in which Japanese industry would again become the workshop of East and Southeast Asia, requiring access to its old colonies and dependencies for markets and resources, but not eventuating in renewed Japanese militarism (since the United States provided for Japan’s defense—then and ever since). When Secretary of State George Marshall wrote a note to Dean Acheson on January 29, 1947, saying, “Please have plan drafted of policy to organize a definite government of So. Korea and

connect up [sic]

its economy with that of Japan,” he captured with pith and foresight the future direction of U.S. policy toward Korea from 1947 down to the normalization of South Korean relations with Japan in 1965. Acheson later became the prime internal advocate of keeping southern Korea in the zone of American and Japanese influence, and single-handedly scripted the American intervention in the Korean War.

The Republic of Korea, led by Syngman Rhee, was founded on August 15, 1948, with MacArthur standing proudly on the platform. Rhee was chosen by a legislature that emerged from a UN-observed election in May 1948, a result that John Foster Dulles had shepherded through the General Assembly. These elections

corresponded to the very limited franchise established under the Japanese, with voting restricted to landowners and taxpayers in the larger towns, elders voting for everyone else at the village level, and gendarmes and youth groups around all the polling places. Likewise, the United Nations “was a relatively small body in 1947 and effectively dominated by the United States.”

4

The Soviets could veto Security Council resolutions, but the United States controlled the General Assembly. Nonetheless, the UN commissioners declared the election to be a free and fair one in those parts of Korea to which they had access (that is, not the North), and thereby the UN imprimatur gave to the Republic of Korea a crucial legitimacy.

HE

S

OUTHWEST OF

K

OREA

D

URING THE

M

ILITARY

G

OVERNMENT

A window into a different future for the American occupation of Korea was opened in the first year after Japan’s defeat—a future that might not have concluded with a divided Korea and an internecine war two years later. The southwest was a microcosm of what happened throughout Korea after the liberation from Japanese imperialism, a fascinating time of crisis politics in action, a fundamental turning point unlike any other in modern Korean history. In South Cholla, later to become the most rebellious province, Americans worked with local leaders and, at least for a while, did not try to change the political complexion of local organs that reflected the will of the people. As the historian Kim Yong-sop has shown in his many works, South Cholla was the site of the Tonghak peasant war in the early 1890s because it occupied the confluence of great Korean wealth—the lush rice paddies of Honam, as the region is known—and Japanese exporters who sent that Korean rice flowing out of southwestern ports to Japan and the world economy. In other words, here was a concentrated intersection of modernity

and empire: Korean desires for autonomy and self-strengthening that took the form of a proto-nationalist rebellion, and imperial interests (Japanese, American, Russian, British) competing with one another in the world economy and determined to take advantage of Korean wealth (and weakness). Long after the Tonghak rebellion was put down, Japanese travel guides in the 1920s still warned against going into the interior of South Cholla, and of course the provincial capital, Kwangju, was the site of a major student uprising against the Japanese in 1929 and an insurrection against the militarists in 1980.

When I toured South Cholla in the 1970s, riding on local buses through the countryside, local people frequently stared at me with uncomplicated, straightforward hatred, something I had rarely experienced elsewhere in Korea. The roads were still mostly hard-packed dirt, sun-darkened peasants bent over ox-driven plows in the rice paddies or shouldered immense burdens like pack animals, thatch-roofed homes were sunk in conspicuous privation, old Japanese-style city halls and railroad stations were unchanged from the colonial era. At unexpected moments along the way, policemen would materialize from nowhere and waylay the bus to check the identification cards of every passenger, amid generalized sullenness and hostility that I had seen before only in America’s urban ghettos.

Things might have been different. It is a paradox of the American Military Government (AMG) that its most successful program in the first year of occupation was in South Cholla. After the Japanese defeat, local organs of Yo Un-hyong’s founding organization had established themselves, and quickly came to be known as “people’s committees.” The late president Kim Dae Jung joined one in Mokpo at the time, something that the militarists in Seoul always held against him (and was part of his indictment for sedition by Chun Doo Hwan in 1980). These committees were patriotic and anticolonial groupings with a complicated political complexion, but Americans in Seoul quickly placed them all under the rubric of “Communists.” (Indeed, as we have seen, Hodge “declared war” on communism in the southern zone on the very early date of December 12, 1945.) But in the southwest, American civil affairs teams worked with local committees for more than a year (and for nearly three years on Cheju Island), something that I first learned about by reading E. Grant Meade’s

American Military Government in Korea

.

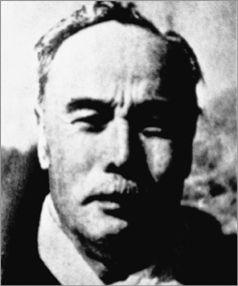

Yo Un-hyong, founder of the Korean People’s Republic (South).

American military forces did not arrive in the provincial capital of Kwangju until October 8, 1945 (a month after they got to Seoul), and civil affairs teams did not show up until October 22. They soon recognized that people’s committees controlled almost the entire province. In charge in Kwangju was Kim Sok, who had spent eleven years as a political prisoner of the Japanese. But in Posong and Yonggwang, landlords ran the committee, and police who had served the Japanese remained in control of small towns. In the coal

town of Hwasun, miners ran the local committee. Several committee elections had been held since August 15 in Naju, Changhung, and other places, excluding only officials who had served the Japanese in the previous decade. Americans in Kwangju, like those in Seoul, wanted to revive the defunct Japanese framework of government and even retained the former provincial governor, Yaki Nobuo, until December (he provided them with secret lists of cooperative Koreans). Kim Sok was arrested on October 28 on trumped-up charges of running an “assassination plot.” His trial, according to an American who witnessed it, was a complete travesty. Soon he was back in his familiar surroundings of the previous decade: prison.

Other Americans, however, recognized that the people’s committees represented “a designation applied to some faction in every town,” with its influence and character varying from place to place: “In one county, it represents the ‘roughnecks’; in another, it is perhaps the only political party and represents no radical expressions; in others, it may even possibly have the [former] county magistrate as its party leader.” Lt. Col. Frank E. Bartlett ran the 45th Military Government team, one of the only such teams to have been trained specifically for Korea (the vast majority had been trained for occupation duty in Japan), and urged his men to know the tenor of local political opinion. This resulted in attempts to “reorganize” the committees in several counties, but basically Bartlett’s group allowed most committees in the province to operate until the fall of 1946. A key reason: the Americans could find no evidence that the committees were controlled “from a strong central headquarters.”

5

It all ended in bloodshed a year later. I still remember the day that I read in the National Archives a report entitled “Cholla-South Communist Uprising of November 1946,” thirty-nine pages long.

6

Uprisings had begun in Taegu almost a month earlier, and had followed a classic pattern of peasant war: rebellions in one county would move to the next and then the next, like billiard balls striking each other. This major uprising was the result of intense Korean

frustrations with the first year of American occupation and the suppression of the people’s committees in the southeastern provinces, and the increasing tendency for the same thing to happen in the southwest. It was entirely indigenous to the southernmost part of the peninsula, having nothing to do with North Korea or with communism. This report detailed more than fifty incidents in November 1945 of the following kind:

Mob composed of people’s committees types attacked police box; police fired into mob, killing six.

1,000 attacked police station … cops fired 100 rounds into mob killing (unknown).

Police fired on mob of 3,000, killing 5.

Police fired into mob of 60 … tactical [American] troops called out; captured 6 bamboo spears and 2 sabers.

600–800 marched on police; police killed 4.

7

The report went on like this, listing a myriad of small peasant wars. When the reader finally reaches the end of the report, he realizes that he stares into an abyss containing the bodies of countless Cholla peasants. In recent years a single incident of this type would have gained national and international attention, but these distant events remain an unknown moment of history along the dusty roads and “parched hills” of Cholla that Kim Chi Ha commemorated in his poem “The Road to Seoul”: except to those who witnessed them, or those who died.

What happened to the families of the dead—how do they commemorate a battle that no one ever heard of? How can Americans occupy a country and, a year later, find themselves firing on people about whom they know next to nothing, but conveniently label as faceless “Communists” or inchoate “mobs”? Are some of these same Americans not living still today, with memories of a peasant war in South Cholla in the fall of 1946? Were they never able to connect

the dots between the indigenous organs of self-government that Koreans fashioned in the aftermath of four decades of brutal colonial rule, and the peasants armed with the tools of their trade, being cut down like rice shoots by the same treacherous Koreans who had served the Japanese?

HE

L

IBERATION IN

S

AMCHOK

Samchok is a port on the upper east coast of South Korea, about fifty miles from the 38th parallel.

8

The large Japanese cement firm Onoda opened a number of plants in Korea during the colonial period; all were in northern Korea except for the one in Samchok. As in most factories elsewhere, a self-governing committee drawn from the factory workers immediately took over the factory on August 15, so that everything could be run by Koreans with their own hands. They proceeded to manage the factory for months and years, under the leadership of Oh Pyong-ho, who had come to the plant when he graduated from engineering school in 1943 and had moved rapidly upward during the war, as six Japanese engineers were drafted away for work in the army—a general pattern in the last decade of colonial rule. He had apprenticed under Kusugawa Shintaro, the head of the Engineering Bureau at the plant, a second-generation colonizer who began work at the Sunghori factory in the north in 1928. But Oh was still only twenty-five in 1945, the eldest son of a landed family from Chinju.

U Chin-hong was one of the skilled workers in the plant, having been born in Samchok in 1920 and later graduated from Sunlin Commercial Higher Common School in Seoul (where I happened to teach English when I was in the Peace Corps). By 1943 he was a skilled worker in the Engineering Bureau. Unlike in the north, where Japanese technicians were often kept on at the factories for up to three years, none were kept at the Samchok factory—and so

Koreans moved into technical and managerial positions instantly at liberation.