The Korean War: A History (20 page)

Read The Korean War: A History Online

Authors: Bruce Cumings

Gen. Chong Il-gwon at the Mount Chiri guerrilla suppression command.

U.S. National Archives

Gen. Chae Pyong-dok, known as “Fatty” to Americans. James Hausman is second from right. Circa 1949.

U.S. National Archives

On October 20 the American G-2 intelligence chief recommended that KMAG “handle [the] situation” and command the army in restoring order “without intervention of U.S. troops.” Roberts said that he planned “to contain and suppress the rebels at [the] earliest moment,” and formed a party to fly to Kwangju on the afternoon of October 20 to command the operation. It consisted of Hausman, Reed, and a third American from KMAG; also an American in the Counter-Intelligence Corps, and Col. Chong Il-gwon. The next day Roberts met with the Constabulary commander Song Ho-song and urged him “to strike hard everywhere … and allow no obstacles to stop him.” Roberts’s “Letter of Instruction” to Song read,

Your mission is to meet the rebel attack with an overwhelmingly superior force and to crush it.… Because of their political

and strategic importance, it is essential that Sunchon and Yosu be recaptured at an early date. The liberation of these cities from the rebel forces will be moral and political victories of great propaganda value.

American C-47 transports ferried Korean troops, weapons, and other matériel; KMAG spotter planes surveilled the area throughout the period of the rebellion; American intelligence organizations worked intimately with U.S. Army and KNP counterparts.

30

As guerrillas built up their strength on the mainland after Yosu, American advisers were all over the war zones in the South, constantly shadowing their Korean counterparts and urging them to greater effort. The man who distinguished himself in this was James Hausman, one of the key organizers of the suppression of the Yosu rebellion, who spent the next three decades as perhaps the most important American operative in Korea, the liaison and nexus point between the American and Korean militaries and their intelligence outfits. Hausman termed himself the father of the Korean Army in an interview, which was not far from the truth. He said that everyone knew this, including the Korean officers themselves, but could not say it publicly. In off-camera remarks, meanwhile, Hausman said that Koreans were “brutal bastards,” “worse than the Japanese”; he sought to make their brutality more efficient by showing them, for example, how to douse corpses of executed people with gasoline, thus to hide the method of execution or blame it on Communists.

31

Back in the United States, hardly anyone has ever heard of Hausman.

If the Rhee regime had one unqualified success, viewed through the American lens, it was the apparent defeat of the southern partisans by the spring of 1950. A year before, it had appeared that the guerrilla movement would only grow with the passage of time; but a major suppression campaign begun in the fall of 1949 resulted in high body counts and a perception that the guerrillas could no longer mount significant operations when they would be expected to—as the spring foliage returned in early 1950. Both Acheson and Kennan saw the suppression of the internal threat as the litmus test of the Rhee regime’s continence: if this worked, so would American-backed containment; if it did not, the regime would be viewed as another Kuomintang (Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party). Col. Preston Goodfellow, formerly the deputy director of the wartime OSS, had told Rhee in late 1948, in the context of a letter where he referred to his “many opportunities to talk with [Dean

Acheson] about Korea,” that the guerrillas had to be “cleaned out quickly … everyone is watching how Korea handles the Communist threat.” A weak policy would lose support in Washington; handle the threat well, and “Korea will be held in high esteem.”

32

American backing was thus crucial to the very willingness of the ROK Army to fight the guerrillas, whether on Cheju or the mainland.

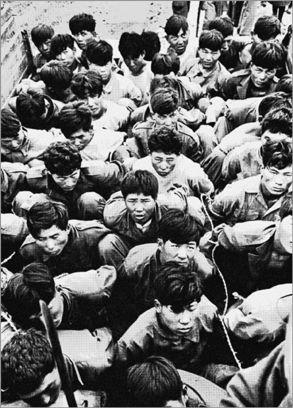

Rebels trussed up during the Yosu rebellion, 1948.

U.S. National Archives

Americans sang the praises of the Rhee regime’s counterinsurgency campaign, even as internal accounts recorded nauseating atrocities. As early as February 1949, Drumwright reported that in South Cholla “there was some not very discriminating destruction of villages” by the ROKA; but a week later he demonstrated his own support for such measures (if discriminate): “the only answer to the Communist threat is for non-Communist youth, after weeding out, to be organized just as tightly and for just as ruthless action as their Leftist counterparts.” He also suggested that American missionaries be utilized for information on the guerrillas.

33

The Americans and the Koreans were in constant conflict over proper counterinsurgent methods, but out of this tension came a mix of American methods and the techniques of suppression the Japanese had developed in Manchuria, for combating guerrillas in cold-weather, mountainous terrain, implemented by Korean officers who had served the Japanese (often in Manchuria). Winter drastically shifted the advantage to suppression forces, as we have seen; large units established blockades while small search-and-destroy units scoured the mountains for guerrillas.

34

The American journalist Hugh Deane argued presciently in March 1948 that Korea would soon come to resemble the civil wars in Greece or north China: as in Greece, “North Korea will be accused of sending agitators and military equipment south of the 38th parallel and the Korean problem will be made to look as if it were simply southern defense against northern aggression.” Yet the worst problem, he thought, would come in the southwestern Chollas, as far from North Korea as any region save Cheju—which developed

the biggest insurgency of all.

35

As it happened, Deane’s prediction was right on all counts: this was where the insurgency was strongest, and this became the American line—and not only that, but the judgment of history. To the extent that anyone knows about the guerrilla conflict, it is assumed to be externally induced, by North Koreans with Soviet backing and weapons, with the Americans standing idly by while the Rhee regime fought the infiltrators. Yet the evidence shows that the Soviets had no involvement with the southern partisans, the North Koreans were connected mainly to attempts at infiltration and guerrillas in northeastern Kangwon province, while the seemingly uninvolved Americans organized and equipped the southern counterinsurgent forces, gave them their best intelligence materials, planned their actions, and often commanded them directly.

Walter Sullivan, a

New York Times

correspondent, was almost alone among foreign journalists in seeking out the truth of the guerrilla war on the mainland and Cheju. Large parts of southern Korea, he wrote in early 1950, “are darkened today by a cloud of terror that is probably unparalleled in the world.” Guerrillas made brutal assaults on police, and the police took the guerrillas to their home villages and tortured them for information. Then the police shot them, and tied them to trees as an object lesson. The persistence of the guerrillas, he wrote, “puzzles many Americans here,” as does “the extreme brutality” of the conflict. But Sullivan went on to argue that “there is great divergence of wealth” in the country, with both middle and poor peasants living “a marginal existence.” He interviewed ten peasant families; none owned all their own land, and most were tenants. The landlord took 30 percent of tenant produce, but additional exactions—government taxes, and various “contributions”—ranged from 48 to 70 percent of the annual crop.

36

The primary cause of the South Korean insurgency was the ancient curse of average Koreans—the social inequity of land relations and the huge gap between a tiny elite of the rich and the vast majority of the poor.

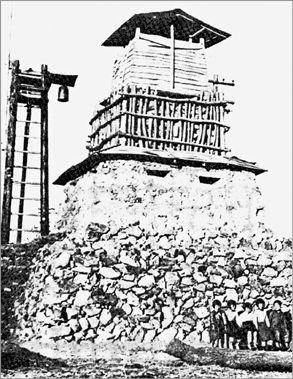

Guerrilla suppression fort, 1949.

Walter Sullivan

In the end upward of 100,000 Koreans in the southern part were killed in political violence

before

the Korean War; once the war began at least another 100,000 were killed, as we will see. The Spanish civil war is well known to have been fratricidal, bloody, and to have generated enmities that lasted for half a century. Recent scholarship on political killings under Franco’s terror during and after this war (still not a full accounting and one covering just thirty-seven of fifty provinces) suggests that about 101,000 people were killed; factoring in the other thirteen provinces would suggest a total figure somewhere between 130,000 and 200,000.

37

Spain may

be the best comparison for a Korean civil war that began well before June 1950 and still goes on today.

The insurrections on Cheju Island and in the southwest were inflamed by a brutal Japanese occupation that led to a vast uprooting of the population, the simple justice of the local administration that took effective power on the island in 1945 and held it until 1948, and the elemental injustice of the mainlander dictatorship that Syngman Rhee imposed and that the American legal authorities did nothing about—except to aid and abet it. It was on this hauntingly beautiful island that the postwar world first witnessed American culpability for unrestrained violence against indigenous peoples fighting for self-determination and social justice.

ATTLES

A

LONG THE

P

ARALLEL

The ROK quickly expanded its armed forces in response to internal rebellion and the North Korean threat. By late summer 1949 it had upward of 100,000 troops, a figure the North would not reach until spring 1950. The United States, however, pursued a civil-war deterrent in Korea, hoping to restrain both the enemy and the ally; it therefore refused to equip this army with heavy weaponry that could be used to support an invasion of the North, such as tanks and an air force, and tried to keep hotheaded Southern commanders from provoking conflict along the 38th parallel. They did not succeed in the latter case; much of the extensive fighting along the border that lasted from May to December 1949 was said by internal American accounts to have been started by Southern forces, and was a major reason for the posting of UN military observers in Korea in 1950—to watch

both

the North and the South.

Although the South launched many small raids across the parallel before the summer of 1949, with the North happy to reciprocate, the important border battles began at Kaesong on May 4, 1949, in an engagement that the South started. It lasted about four days and took an official toll of four hundred North Korean and twenty-two South Korean soldiers, as well as upward of a hundred civilian deaths in Kaesong, according to American and South Korean figures.

38

The South committed six infantry companies and several battalions, and two of its companies defected to the North (incongruous in their American military uniforms, Pyongyang made quick propaganda use of them). Months later, based on the defectors’ testimony, the North Koreans claimed that several thousand troops led by Kim Sok-won attacked across the parallel on the

morning of May 4, near Mount Songak, inaugurating border fighting that lasted for six months.

39

Kim was the commander of the critically important 1st Division; he was also from northern Korea and, as we have seen, had tracked Kim Il Sung at Japan’s behest in the Manchurian wilderness in the late 1930s. Syngman Rhee came to rely on Kim and a small core of Manchurian officers after coming to power in 1948, mainly those who had experience in Japanese counterinsurgency. A few weeks after the Kaesong battle, Kim Sok-won gave the United Nations Commission on Korea (UNCOK) a briefing in his status as commander of ROKA forces along the 38th parallel: North and South “may engage in major battles at any moment,” he said; Korea has entered into “a state of warfare.” “We should have a program to recover our lost land, North Korea, by breaking through the 38th border which has existed since 1945”; the moment of major battles, Kim told UNCOK, is rapidly approaching.

40