The Korean War: A History (22 page)

Read The Korean War: A History Online

Authors: Bruce Cumings

Pretensions of precision targeting were put out for public consumption, while secret estimates showed that fewer than half the large bombs hit their targets. But in favorable atmospheric conditions these bombs ignited firestorms that razed Darmstadt, Heilbronn, Pforzheim, Wurzburg, and, of course, Hamburg (40,000 deaths), Dresden (12,000), and Tokyo (88,000). Or in Winston Churchill’s words, “We will make Germany a desert, yes, a desert” through the power of incendiary bombing—only “an absolutely devastating, exterminating attack by very heavy bombers” would finally bring Hitler to his knees. The goal was to destroy the morale of the enemy and the people, a horizon that receded even as the attacks intensified.

2

The postwar

U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey

demonstrated that enemy morale was mostly unaffected by the bombing, but also that the actual level of civilian deaths was less than predicted—that is, “far removed from the generally anticipated total of several millions.” Morale was not broken, and even the harvest of blackened, scorched, blasted, or asphyxiated human beings was anticlimactic (not even several millions). Furthermore, both countries were democracies, so some rose up to criticize mass attacks against civilians (Bishop George Bell told the House of Lords that “to obliterate a whole town” because it may have some industrial targets violated “a fair balance between the means employed and the purpose achieved”

3

).

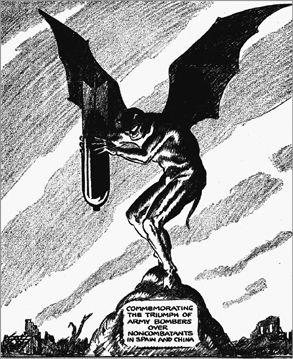

Herblock’s depiction of bombing of civilians by Franco’s Spain and by Japan, 1937.

Copyright by the Herb Block Foundation

Top air force officers decided to repeat “the fire” in Korea, a wildly disproportionate scheme in that North Korea had no pretense or possibility of a similar city-busting capability. Whereas German fighter planes and antiaircraft batteries made these allied bombing runs harrowing, with high loss of life among British and American pilots and crew, American pilots had virtual free-fire zones until later in the war, when formidable Soviet MIGs were deployed. Curtis LeMay subsequently said that he had wanted to burn down North Korea’s big cities at the inception of the war, but the Pentagon refused—“it’s too horrible.” So over a period of three years, he went on, “We burned down

every [sic]

town in North Korea and South Korea, too.… Now, over a period of three years this is palatable, but to kill a few people to stop this from happening—a lot of people can’t stomach it.”

4

To take just one example of these “limited” raids, on July 11, 1952, an “all-out assault” on Pyongyang involved 1,254 air sorties by day and 54 B-29 assaults by night, the prelude to bombing thirty other cities and industrial objectives under “operation PRESSURE PUMP.” Highly concentrated incendiary bombs were followed up with delayed demolition explosives.

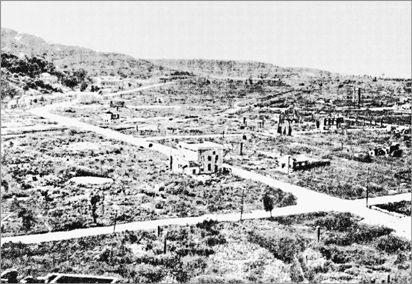

Part of the city of Wonsan, under siege for 273 days.

U.S. National Archives

By 1968 the Dow Chemical Company, a major manufacturer of napalm, could not enter most college campuses to recruit employees because of napalm’s use in Vietnam, but oceans of it were dropped on Korea silently or without notice in America, with much more devastating effect, since the DPRK had many more populous cities and urban industrial installations than did Vietnam. Furthermore, the U.S. Air Force loved this infernal jelly, its “wonder weapon,” as attested to by many articles in “trade” journals of the

time.

*

One day Pfc. James Ransome, Jr.’s unit suffered a “friendly” hit of this wonder weapon: his men rolled in the snow in agony and begged him to shoot them, as their skin burned to a crisp and peeled back “like fried potato chips.” Reporters saw case after case of civilians drenched in napalm-the whole body “covered with a hard, black crust sprinkled with yellow pus.”

5

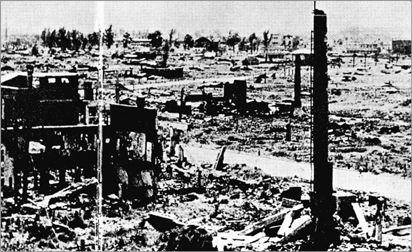

Part of the city of Pyongyang, at the end of the war.

Courtesy of Chris Springer

Korea recapitulated the air force’s mantra from World War II, that firebombing would erode enemy morale and end the war sooner, but the interior intent was to destroy Korean society down to the individual constituent: General Ridgway, who at times deplored the free-fire zones he saw, nonetheless wanted bigger and better napalm bombs (thousand-pound versions to be dropped from B-29s) in early 1951, thus to “wipe out all life in tactical locality and save the lives of our soldiers.” “If we keep on tearing the

place apart,” Secretary of Defense Robert Lovett said, “we can make it a most unpopular affair for the North Koreans. We ought to go right ahead.” (Lovett had advised in 1944 that the Royal Air Force had no restrictions on attacks against enemy territory, so the American bombers should “wipe out the town as the RAF does.”)

6

Another irony of the air war against Germany and Japan is that the worst civilian losses came after Arthur Harris, RAF Bomber Command chief, and Carl Spaatz, commander of U.S. Army Air Forces, had run out of targets—months before the most destructive incendiary attacks in March 1945. Cities were razed “because the bombing offensive had long ago become an end in itself, with its own momentum, its own purpose, devoid of tactical or strategic value, indifferent to the needless suffering and destruction it caused.”

7

Within months few big targets remained in Korea, either; in late 1951 the air force judged that there were no remaining targets worthy of using the “Tarzan,” its largest conventional bomb at 12,000 pounds, which had been deployed in December 1950 to try to decapitate DPRK leaders in deep bunkers. Twenty-eight of them had been used in the war.

8

The opening of North Korean dams was another carryover from World War II. In May 1943 when the water level was highest (as in Korea), “Operation Chastise” attacked two dams on the Ruhr; the Moehne dam had a height of 130 feet and was 112 feet thick at its base; the Eder River dam held 7 billion cubic feet of water. “A tidal wave of 160 million tons of water, with a vertex thirty feet high,” inundated five towns. The Royal Air Force considered this to be its “most brilliant action ever carried out.” Friedrich concluded that total war consumes human beings totally—“and their sense of humanity is the first thing to go.”

9

Air force plans for attacks on North Korea’s large dams originally envisioned hitting twenty of them, thus to destroy 250,000 tons of rice that would soon be harvested. In the event, bombers hit three dams in mid-May 1953, just as the rice was newly planted: Toksan, Chasan, and Kuwonga; shortly thereafter two more were attacked, at Namsi and Taechon. These are usually called “irrigation dams” in the literature, but they were major dams akin to many large dams in the United States. The great Suiho Dam on the Yalu River was second in the world only to Hoover Dam, and was first bombed in May 1952 (although never demolished, for fear of provoking Beijing and Moscow). The Pujon River dam was designed to hold 670 million cubic meters of water, and had a pressure gradient of 999 meters; the dam’s power station generated 200,000 kilowatts from the water.

10

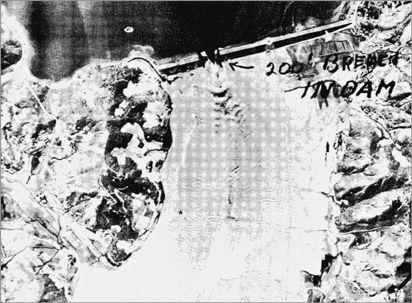

According to the official U.S. Air Force history, when fifty-nine F-84 Thunderjets breached the high containing wall of Toksan on May 13, 1953, the onrushing flood destroyed six miles of railway, five bridges, two miles of highway, and five square miles of rice paddies. The first breach at Toksan “scooped clean” twenty-seven miles of river valley, and sent water rushing even into Pyongyang. After the war it took 200,000 man-days of labor to reconstruct the reservoir.

But as with so many aspects of the war, no one seemed to notice back home: only the very fine print of

New York Times

daily war reports mentioned the dam hits, with no commentary.

11

The Toksan Dam, breached by American bombers.

U.S. Air Force and U.S. National Archives

HE

U

LTIMATE

F

IRE

The United States also considered using atomic weapons several times, and came closest to doing so in early April 1951—precisely the time that Truman removed MacArthur. It is now clear that Truman did not remove MacArthur simply because of his repeated insubordination, but also because he wanted a reliable commander on the scene should Washington decide to use nuclear weapons: that is, Truman traded MacArthur for his atomic policies. On March 10, 1951, MacArthur asked for a “‘D’ Day atomic capability,” to retain air superiority in the Korean theater, after intelligence sources suggested the Soviets appeared ready to move air divisions to the vicinity of Korea and put Soviet bombers into air bases in Manchuria (from which they could strike not just Korea but also American bases in Japan), and after the Chinese massed huge new forces near the Korean border. On March 14, Vandenberg wrote, “Finletter and Lovett alerted on atomic discussions. Believe everything is set.” At the end of March, Stratemeyer reported that atomic bomb loading pits at Kadena Air Base on Okinawa were operational; the bombs were carried there unassembled, and put together at the base—lacking only the essential nuclear cores, or “capsules.” On April 5 the JCS ordered immediate atomic retaliation against Manchurian bases if large numbers of new troops came into the fighting, or, it appears, if bombers were launched against American assets from there.

That same day Gordon Dean, chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, began arrangements for transferring nine Mark IV nuclear capsules to the air force’s 9th Bomb Group, the designated carrier of the weapons. General Bradley (JCS chairman) got Truman’s approval for this transfer of the Mark IVs “from AEC to military custody”

on April 6, and the president signed an order to use them against Chinese and North Korean targets. The 9th Bomb Group deployed to Guam. “In the confusion attendant upon General MacArthur’s removal,” however, the order was never sent. The reasons were two: Truman had used this extraordinary crisis to get the JCS to approve MacArthur’s removal (something Truman announced on April 11), and the Chinese did not escalate the war. So the bombs were not used. But the nine Mark IVs remained in air force custody after their transfer on April 11. The 9th Bomb Group remained on Guam, however, and did not move on to the loading pits at Kadena AFB in Okinawa.

12