The Lake of Dreams (12 page)

“Is this one of the windows with the border?”

“No, those are all still at the chapel on the depot land. All but the largest one, which was sent out to be cleaned and is on display here for a little while. Want to see it?”

“I do, but I’m afraid I’m interrupting you.”

“That’s okay. I like showing off the window. It’s just in the other room, back where they keep the vestments and the wafers and the wine. Follow me.”

I did. Everything about Keegan was so familiar, the shape of his ears, the swing of his arms, the hair slipping out of the dark blue rubber band he’d used to pull it back.

Do you remember?

I wanted to ask as I followed him through the narrow passage, up three steps into the room.

Those nights when we went out on the lake to watch the moon rise, letting the waves and currents push us where they would?

Keegan unlocked the door and waited for me to step through into the little room, which was oddly shaped, with cupboards and shelves filling all the walls.

“I used to put my robes on in this room. By the way, don’t use that sink.”

Keegan smiled. “Yes. They warned me. A pipe straight to the earth. Communion wine only. No cleaning of brushes.”

“It’s interesting—as if the earth is sacred, like the wine.”

“It is.”

“Interesting, or sacred?”

Keegan considered this. “I meant interesting. But both, I’d say. Come, check out the window—it’s hanging just around the corner, in the alcove.”

I passed the cupboards full of vestments and stopped as I turned the corner, taken aback by the size and beauty of the stained-glass window. It was hanging against a large clear window overlooking the lake, so the mosaic of leaded glass was flooded with light, and colors slanted down from it, falling on my arms and all across my body to the floor. Birds flew through a deep blue sky, and below, multicolored fish swam in a darker sea; vines climbed the edges and flowers bloomed in brilliant hues, and amid the flora there were animals of all kinds, zebras and lizards, rabbits and elephants, surrounded by lush trees whose variegated leaves seemed to flutter. Human figures, too, growing like the trees and flowers from the dark red earth, visibly human but not visibly male or female, standing with lifted arms, their hands transforming into leaves, the leaves in turn forming letters I did not understand. Bordering the lower edge was the familiar row of vine-laced moons. Above these interlocking moons was a single sentence in letters of light-filled gold.

“For she is a breath of the power of God . . . she renews all things.”

“I had no idea it would be so stunning,” I whispered.

“Isn’t it something? The other window—the Joseph window—will be spectacular when it’s finished, too. I can’t wait to see the others in the chapel. This one is the creation story. It hadn’t been completely covered, and when I first saw it, the glass was so filthy I couldn’t even make out the images. Do you see these patterns?” he asked, gesturing to swirls of clear light woven through and around the images. “That’s wind, I finally realized. At first, when the glass was still so dirty, I thought maybe pieces had been broken and replaced, but this glass is original, organic to the design.”

I reached through bands of color-filled air to touch the border of overlapping moons, the intricate vines and flowers of lead. “Here it is again, that pattern.”

“Yes. It must have been a commissioned work. It’s nice stained glass,” he added. “Not Tiffany or La Farge, though there are traces of those influences, but still—very, very good. Whoever made this window was an excellent craftsman, a fine artist. And whoever ordered it had a lot of money.”

I stepped back as far as I could and took some photos with my cell phone. They’d be grainy, and I wished I’d thought to bring my camera.

“Is it very old? It looks old.”

“Well, it’s an Art Nouveau design, but because of the glass I’d place it later than that, maybe 1930 or 1940. The techniques used to make stained glass are ancient, but in the nineteenth century people started simply painting the glass, dropping the leading entirely for a few decades. Then, around the turn of the century, there was a revival of the old ways, which still continues.”

“And the one in your studio? The Joseph window?”

“That’s the same period. The same artist, too, I can almost guarantee. It was probably part of the same commission, along with the windows that are still in the chapel. I don’t know why it wasn’t installed.”

Light fell across me in vibrant patches of blue and green and yellow, and I thought of the fabric with its matching border. The writer of the notes may have woven that cloth, and perhaps she had made these windows, too, or at least been involved in their design. But who was she, the elusive R? Who was she?

“The pattern is so distinctive,” I said. “I’m sure there’s a connection.”

“You know, Lucy, donors used to have artists put figures of loved ones—or even of themselves—into biblical scenes. I’m wondering about the women in the other window. Were they at all familiar?”

“I don’t know. That’s an interesting thought, but I wasn’t really paying attention to the faces. I’d have to look again. But it would take more than a face, anyway. I need a name, a story. I wonder—Keegan, can I go to the chapel to see the other windows?”

“That, I don’t know. It’s still pretty restricted. But I’ll find out.”

Footsteps had been echoing distantly in the sanctuary, then in the hallway; now they drew close and we turned as a woman entered the room. She was tall, though not quite as tall as me, wearing a clerical collar, and maybe a decade older than me. Her blond hair swung near her shoulders.

“Oh,” she said. “Keegan. I didn’t realize anyone was here.”

“Hey, Rev,” he said, smiling. I could tell he liked her. “This is my old friend Lucy Jarrett. We were wild and crazy about each other, once upon a time.”

She smiled and shook my hand. “Suzi Wells.”

“That would be the Reverend Dr. Suzi,” Keegan said.

“Suzi will do,” she said.

“We were just looking at the window,” I explained.

“Ah—I’ve been away all week. I haven’t seen it yet. May I?”

I stepped back as she entered the alcove and paused, stunned, just as I had been, by the breathtaking beauty of the patterns in glass and light.

“Oh, my. It

is

beautiful. Gorgeous. Keegan, is this really the same window?”

“Cleaned up nicely, didn’t it?”

“I can’t believe it. It was so dark before.”

She stepped closer and touched the human figures, their upraised fingers turning into leaves, into language.

“What does it say?”

“It’s Hebrew.

Tehillah,

or praise.

Adamah

.”

“As in Adam and Eve,” Keegan suggested.

Suzi nodded. “Yes, though, actually,

adamah

simply means arable land. In English it translates roughly as

hummus, human

. I think that must be why these figures are growing right out of the earth.” Suzi leaned closer. “So it means something like ‘The People Praise God.’ When did you say this was made?”

“In the 1930s or ’40s, maybe.”

She straightened, thoughtful. “Really? Yet the imagery seems very contemporary. The imagery and the use of that quote.”

“I wondered about the quote,” I said.

She nodded without taking her gaze from the window. “I’d have to look it up to give you the exact chapter and verse, but it’s from the book of Wisdom, praising Wisdom’s many virtues. Some traditions call her Sophia, which of course is the Greek word for

Wisdom

. According to the Scriptures, Wisdom was present at creation. No, I’ll amend that—she was not just present, Wisdom was actively involved in creation. Delighting in it. She’s described as an all-powerful, all-seeing, vivifying force. I imagine that’s what this wind weaving through the scene is all about. Wisdom is associated with the Holy Spirit, too; and

spirit

is a word that also has feminine roots—

ruah

in Hebrew, meaning breath. Present in all things, renewing all things.” She turned to Keegan. “This was made in the 1930s—are you sure?”

“I’m almost certain.”

“Well, that’s remarkable. In recent years there’s been so much interest in recognizing the female imagery and metaphors woven all through Scripture, which have been largely ignored. It wasn’t so common in the 1930s or ’40s, though. I wouldn’t have expected to see it in the artwork of that time. So I’m very curious about this window. It’s just so fascinating.”

She laughed at herself then and stepped back from the window. “Okay—fascinating to me, as a priest and a scholar. Maybe not so fascinating to either of you.”

“Well, it is,” I said. “Though to be honest, for different reasons.” I pointed out the border motif, and told her about the fabric and the papers I’d found stuffed away in the cupola. “I’m startled to find this pattern here, and I’m walking blind, really. I don’t know anything about this person, except that whoever she was, she must have been connected to the family.”

“And to the church as well, I would guess.”

“Right, that’s exactly right. So I was wondering if the church has any records of these windows? Any documents about the original gift?”

Suzi held up her hands. “I really don’t know. That’s a good question. All I know for certain is that the chapel on the land that eventually became the depot was established as an extension of this church sometime in the 1930s. So the dates fit, don’t they? Still, that’s all I can offer. I’m relatively new here. But why not ask Joanna—she’s the church secretary.” Suzi slipped a cell phone from her pocket and checked the time. “She won’t have left for lunch yet. Joanna is very good, and she’s been here several years—if there’s something to be found, she’ll find it.”

We stepped into the hall, which was lined with windows on one side and the framed black-and-white photos of the rectors, going back to 1835, on the other.

“I’ll see you next week, Rev, when the window is ready,” Keegan said. “Tuesday sound right?”

“It does.” She smiled then, standing in the doorway. “You know, Keegan—you’re welcome on Sunday. You, too, Lucy.”

I didn’t answer—the long line of rectors gazing down from the wall made me nervous—but Keegan laughed, as if this were a familiar and comfortable exchange between them. “Thanks, but I don’t like organized religion. No offense. I prefer to pray my own way.”

She smiled. “Let me ask—how is that?”

He grinned. “Well, I take my boat out. I sit on the water and think about the things in my life that haven’t gone so well, and how I could have done some of them differently. And then I think about good things in my life, one by one. I feel thankful.”

The Reverend Dr. Suzi Wells laughed. “Well, I’m not going to argue with that,” she said. “Still, come sometime. I think you’d be surprised.”

Still smiling, she stepped back into the vestment room. Keegan offered to show me the office, but I told him I knew where it was.

“Thanks, though—and for bringing me here.”

He smiled, and held me in his gaze for a moment, and I had the strange sense that time was falling away, that this moment was connected quite directly to the days when we’d been so free and easy with each other. It was all I could do to keep from taking his hand, as I would have done so easily when I was seventeen.

“It’s good to see you, Lucy. Really good. Let me know what you dig up, okay? And I’ll find out about access to the windows in the chapel. Good luck on the treasure hunt, meanwhile.”

The hallways were byzantine, one addition connected to another, but I made my way to the office without getting lost. Joanna, the secretary, was a short, stocky woman with shoulder-length hair full of streaky blond highlights. We’d been talking for several minutes before I realized she’d been a year ahead of me in school, a girl who sat next to me in Spanish class. Now she was married, with two children; her husband worked for the town. I told her the same story I’d told Suzi, about the border in the cloth and the windows, about the notes I’d found. She rummaged through a file cabinet for a few minutes but came up with nothing. “Let me check the archives,” she said, standing up and smoothing down her skirt. “That’s a fancy way of saying I need to go poke around the basement. It shouldn’t take too long.”

I waited in the office, gazing out the arched window where the branches of a gingko tree were swaying, their fan-shaped leaves rippling in the breeze, feeling restless and excited, stirred up in a way that made me think of my early days with Yoshi in Indonesia, when it was becoming clear that life was shifting, changing in some vital way. One discovery by itself—the cloth, the letters, the windows—would have been something to note and then forget, but together they raised questions about my past, which I’d always imagined to be written in stone. It was seismic, in its way, as jolting and unexpected as the trembling of the earth.

Footsteps sounded on the stairs, and then Joanna appeared, a little breathless.

“Well, there wasn’t much of a record,” she said. “At least, not that I could find right away, though I’ll try to look again if I have time. The chapel was built in the late 1930s as an extension of this church. It’s in the church history; ground was broken in April 1938. I have an idea, too, that it was funded by an anonymous donor, though I couldn’t find anything down there about that. All I found was this one receipt with the name of the artist who made the windows.”

She handed me a piece of paper with a formal heading and pale blue lines. The script was neat and careful, the prices logged in columns on the side. It made me think of bills of sale from my childhood at Dream Master, the gray steel case that held the invoice forms, the listing of purchases, all written carefully by hand, whisper-thin sheets of carbon paper layered between the invoice pages.

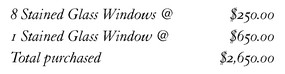

This invoice was dated October 6, 1938, and listed three items.