The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (21 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

The rule nicely interfaces with the mental dictionary:

dog

would be listed as a noun stem meaning “dog,” and -

s

would be listed as a noun inflection meaning “plural of.”

This rule is the simplest, most stripped-down example of anything we would want to call a rule of grammar. In my laboratory we use it as an easily studied instance of mental grammar, allowing us to document in great detail the psychology of linguistic rules from infancy to old age in both normal and neurologically impaired people, in much the same way that biologists focus on the fruit fly

Drosophila

to study the machinery of genes. Though simple, the rule that glues an inflection to a stem is a surprisingly powerful computational operation. That is because it recognizes an abstract mental symbol, like “noun stem,” instead of being associated with a particular list of words or a particular list of sounds or a particular list of meanings. We can use the rule to inflect any item in the mental dictionary that lists “noun stem” in its entry, without caring what the word means; we can convert not only

dog

to

dogs

but also

hour

to

hours

and

justification

to

justifications

. Likewise, the rule allows us to form plurals without caring what the word sounds like; we pluralize unusual-sounding words as in

the Gorbachevs, the Bachs

, and

the Mao Zedongs

. For the same reason, the rule is perfectly happy applying to brand-new nouns, like

faxes, dweebs, wugs

, and

zots

.

We apply the rule so effortlessly that perhaps the only way I can drum up some admiration for what it accomplishes is to compare humans with a certain kind of computer program that many computer scientists tout as the wave of the future. These programs, called “artificial neural networks,” do not apply a rule like the one I have just shown you. An artificial neural network works by analogy, converting

wug

to

wugged

because it is vaguely similar to

hug—hugged, walk-walked

, and thousands of other verbs the network has been trained to recognize. But when the network is faced with a new verb that is unlike anything it has previously been trained on, it often mangles it, because the network does not have an abstract, all-embracing category “verb stem” to fall back on and add an affix to. Here are some comparisons between what people typically do and what artificial neural networks typically do when given a

wug

-test:

VERB

: mail

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY PEOPLE

: mailed

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY NEURAL NETWORKS

: membled

VERB

: conflict

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY PEOPLE

: conflicted

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY NEURAL NETWORKS

: conflafted

VERB

: wink

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY PEOPLE

: winked

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY NEURAL NETWORKS

: wok

VERB

: quiver

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY PEOPLE

: quivered

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY NEURAL NETWORKS

: quess

VERB

: satisfy

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY PEOPLE

: satisfied

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY NEURAL NETWORKS

: sedderded

VERB

: smairf

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY PEOPLE

: smairfed

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY NEURAL NETWORKS

: sprurice

VERB

: trilb

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY PEOPLE

: trilbed

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY NEURAL NETWORKS

: treelilt

VERB

: smeej

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY PEOPLE

: smeejed

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY NEURAL NETWORKS

: leefloag

VERB

: frilg

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY PEOPLE

: frilged

TYPICAL PAST-TENSE FORM GIVEN BY NEURAL NETWORKS

: freezled

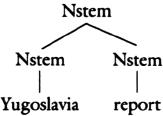

Stems can be built out of parts, too, in a second, deeper level of word assembly. In compounds like

Yugoslavia report, sushi-lover, broccoli-green

, and

toothbrush

,

two stems are joined together to form a new stem, by the rule

Nstem

Nstem Nstem

“A noun stem can consist of a noun stem followed by another noun stem.”

In English, a compound is often spelled with a hyphen or by running its two words together, but it can also be spelled with a space between the two components as if they were still separate words. This confused your grammar teacher into telling you that in

Yugoslavia report

, “Yugoslavia” is an adjective. To see that this can’t be right, just try comparing it with a real adjective like

interesting

. You can say

This report seems interesting

but not

This report seems Yugoslavia

! There is a simple way to tell whether something is a compound word or a phrase: compounds generally have stress on the first word, phrases on the second. A

dark róom

(phrase) is any room that is dark, but a

dárk room

(compound word) is where photographers work, and a darkroom can be lit when the photographer is done. A

black bóard

, (phrase) is necessarily a board that is black, but some

bláckboards

(compound word) are green or even white. Without pronunciation or punctuation as a guide, some word strings can be read either as a phrase or as a compound, like the following headlines:

Squad Helps Dog Bite Victim

Man Eating Piranha Mistakenly Sold as Pet Fish

Juvenile Court to Try Shooting Defendant

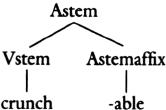

New stems can also be formed out of old ones by adding affixes (prefixes and suffixes), like the -

al, -ize

, and -

ation

I used recursively to get longer and longer words ad infinitum (as in

sensationalizationalization

). For example, -

able

combines with any verb to create an adjective, as in

crunch—crunchable

. The suffix -

er

converts any verb to a noun, as in

crunch—cruncher

, and the suffix -

ness

converts any adjective into a noun, as in

crunchy-crunchiness

.

The rule forming them is

Astem

Stem Astemaffix

“An adjective stem can consist of a stem joined to a suffix.”

and a suffix like -

able

would have a mental dictionary entry like the following:

-able:

adjective stem affix

means “capable of being X’d”

attach me to a verb stem

Like inflections, stem affixes are promiscuous, mating with any stem that has the right category label, and so we have

crunchable, scrunchable, shmooshable, wuggable

, and so on. Their meanings are predictable: capable of being crunched, capable of being scrunched, capable of being shmooshed, even capable of being “wugged,” whatever

wug

means. (Though I can think of an exception: in the sentence

I asked him what he thought of my review in his book, and his response was unprintable

, the word

unprintable

means something much more specific than “incapable of being printed.”)

The scheme for computing the meaning of a stem out of the meaning of its parts is similar to the one used in syntax: one special element is the “head,” and it determines what the conglomeration refers to. Just as the phrase

the cat in the hat

is a kind of cat, showing that

cat

is its head, a

Yugoslavia report

is a kind of report, and

shmooshability

is a kind of ability, so

report

and -

ability

must be the heads of those words. The head of an English word is simply its rightmost morpheme.

Continuing the dissection we can tease stems into even smaller parts. The smallest part of a word, the part that cannot be cut up into any smaller parts, is called its root. Roots can combine with special suffixes to form stems. For example, the root

Darwin

can be found inside the stem

Darwinian

. The stem

Darwinian

in turn can be fed into the suffixing rule to yield the new stem

Darwinianism

. From there, the inflectional rule could even give us the word

Darwinianisms

, embodying all three levels of word structure: