The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (22 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

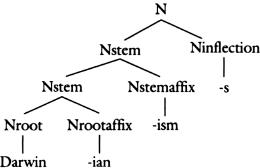

Interestingly, the pieces fit together in only certain ways. Thus

Darwinism

, a stem formed by the stem suffix -

ism

, cannot be a host for -

ian

, because -

ian

attaches only to roots; hence

Darwinismian

(which would mean “pertaining to Darwinism”) sounds ridiculous. Similarly,

Darwinsian

(“pertaining to the two famous Darwins, Charles and Erasmus”),

Darwinsianism

, and

Darwinsism

are quite impossible, because whole inflected words cannot have any root or stem suffixes joined to them.

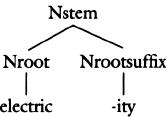

Down at the bottommost level of roots and root affixes, we have entered a strange world. Take

electricity

. It seems to contain two parts,

electric

and -

ity:

But are these words really assembled by a rule, gluing a dictionary entry for -

ity

onto the root

electric

, like this?

Nstem

Nroot Nrootsuffix

“A noun stem can be composed of a noun root and a suffix.”

-

ity:noun root suffix

means “the state of being X”

attach me to a noun root

Not this time. First, you can’t get

electricity

simply by gluing together the word

electric

and the suffix -

ity

—that would sound like “electrick itty.” The root that -

ity

is attached to has changed its pronunciation to “electríss.” That residue, left behind when the suffix has been removed, is a root that cannot be pronounced in isolation.

Second, root-affix combinations have unpredictable meanings; the neat scheme for interpreting the meaning of the whole from the meaning of the parts breaks down.

Complexity

is the state of being complex, but

electricity

is not the state of being electric (you would never say that the electricity of this new can opener makes it convenient); it is the force powering something electric. Similarly,

instrumental

has nothing to do with instruments,

intoxicate

is not about toxic substances, one does not recite at a

recital

, and a five-speed

transmission

is not an act of transmitting.

Third, the supposed rule and affix do not apply to words freely, unlike the other rules and affixes we have looked at. For example, something can be

academic

or

acrobatic

or

aerodynamic

or

alcoholic

, but

academicity, acrobaticity, aerodynamicity

, and

alcoholicity

sound horrible (to pick just the first four words ending in

-ic

in my electronic dictionary).

So at the third and most microscopic level of word structure, roots and their affixes, we do not find bona fide rules that build words according to predictable formulas,

wug

-style. The stems seem to be stored in the mental dictionary with their own idiosyncratic meanings attached. Many of these complex stems originally were formed after the Renaissance, when scholars imported many words and suffixes into English from Latin and French, using some of the rules appropriate to those languages of learning. We have inherited the words, but not the rules. The reason to think that modern English speakers mentally analyze these words as trees at all, rather than as homogeneous strings of sound, is that we all sense that there is a natural break point between the

electric

and the -

ity

. We also recognize that there is an affinity between the word

electric

and the word

electricity

, and we recognize that any other word containing -

ity

must be a noun.

Our ability to appreciate a pattern inside a word, while knowing that the pattern is not the product of some potent rule, is the inspiration for a whole genre of wordplay. Self-conscious writers and speakers often extend Latinate root suffixes to new forms by analogy, such as

religiosity, criticality, systematicity, randomicity, insipidify, calumniate, conciliate, stereotypy, disaffiliate, gallonage

, and

Shavian

. The words have an air of heaviosity and seriosity about them, making the style an easy target for parody. A 1982 editorial cartoon by Jeff Mac-Nelly put the following resignation speech into the mouth of Alexander Haig, the malaprop-prone Secretary of State:

I decisioned the necessifaction of the resignatory action/ option due to the dangerosity of the trendflowing of foreign policy away from our originatious careful coursing towards consistensivity, purposity, steadfastnitude, and above all, clarity.

Another cartoon, by Tom Toles, showed a bearded academician explaining the reason verbal Scholastic Aptitude Test scores were at an all-time low:

Incomplete implementation of strategized programmatics designated to maximize acquisition of awareness and utilization of communications skills pursuant to standardized review and assessment of languaginal development.

In the culture of computer programmers and managers, this analogy-making is used for playful precision, not pomposity.

The New Hacker’s Dictionary

, a compilation of hackish jargon, is a near-exhaustive catalogue of the not-quite-freely-extendible root affixes in English:

ambimoustrous

adj. Capable of operating a mouse with either hand.barfulous

adj. Something that would make anyone barf.bogosity

n. The degree to which something is bogus.bogotify

v. To render something bogus.bozotic

adj. Having the quality of Bozo the Clown.cuspy

adj. Functionally elegant.depeditate

v. To cut the feet off of (e.g., while printing the bottom of a page).dimwittery

n. Example of a dim-witted statement.geekdom

n. State of being a techno-nerd.marketroid

n. Member of a company’s marketing department.mumblage

n. The topic of one’s mumbling.pessimal

adj. Opposite of “optimal.”wedgitude

n. The state of being wedged (stuck; incapable of proceeding without help).wizardly

adj. Pertaining to expert programmers.

Down at the level of word roots, we also find messy patterns in irregular plurals like

mouse-mice

and

man-men

and in irregular past-tense forms like

drink-drank

and

seek-sought

. Irregular forms tend to come in families, like

drink-drank, sink-sank, shrink-shrank, stink-stank, sing-sang, ring-rang, spring-sprang, swim-swam

, and

sit-sat

, or

blow-blew, know-knew, grow-grew, throw-threw, fly-flew

, and

slay-slew

. This is because thousands of years ago Proto-Indo-European, the language ancestral to English and most other European languages, had rules that replaced one vowel with another to form the past tense, just as we now have a rule that adds -

ed

. The irregular or “strong” verbs in modern English are mere fossils of these rules; the rules themselves are dead and gone. Most verbs that would seem eligible to belong to the irregular families are arbitrarily excluded, as we see in the following doggerel:

Sally Salter, she was a young teacher who taught,

And her friend, Charley Church, was a preacher who praught;

Though his enemies called him a screecher, who scraught.

His heart, when he saw her, kept sinking, and sunk;

And his eye, meeting hers, began winking, and wunk;

While she in her turn, fell to thinking, and chunk.

In secret he wanted to speak, and he spoke,

To seek with his lips what his heart long had soke,

So he managed to let the truth leak, and it loke.

The kiss he was dying to steal, then he stole;

At the feet where he wanted to kneel, then he knole;

And he said, “I feel better than ever I fole.”

People must simply be memorizing each past-tense form separately. But as this poem shows, they can be sensitive to the patterns among them and can even extend the patterns to new words for humorous effect, as in Haigspeak and hackspeak. Many of us have been tempted by the cuteness of

sneeze-snoze, squeeze-squoze, take-took-tooken

, and

shit-shat

, which are based on analogies with

freeze-froze, break-broke-broken

, and

sit-sat

. In

Crazy English

Richard Lederer wrote an essay called “Foxen in the Henhice,” featuring irregular plurals gone mad:

booth-beeth, harmonica-harmonicae, mother-methren, drum-dra, Kleenex-Kleenices

, and

bathtub-bathtubim

. Hackers speak of

faxen, VAXen, boxen, meece

, and

Macinteesh. Newsweek

magazine once referred to the white-caped, rhinestone-studded Las Vegas entertainers as

Elvii

. In the

Peanuts

comic strip, Linus’s teacher Miss Othmar once had the class glue eggshells into model

igli

. Maggie Sullivan wrote an article in the

New York Times

calling for “strengthening” the English language by conjugating more verbs as if they were strong: