The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (16 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

I never can hear a crowd of people singing and gesticulating altogether at an Italian opera without fancying myself at Athens, listening to that particular tragedy by Sophocles in which he introduces a full chorus of turkeys who set about bewailing the death of Meleager.

Poe is referring to

Meleager

, the lost tragedy of Sophocles, which, as you’ve probably assumed, didn’t actually have a chorus of turkeys. This is certainly not to disparage their vocal stylings, but turkeys simply didn’t make it to Europe until 1511—a good 2000 years after Sophocles wrote his tragedies in Athens. So how did they show up at the Greek amphitheater two millennia early? And why does this bird always seem to be named after countries? Besides Turkey the list includes India, the source of the name in dozens of languages including French

dinde

, from a contraction of the original d’Inde, “of India,” Turkish

hindi

,

and Polish

indik

. And there’s Peru (the source of the word

peru

in both Hindi and Portuguese) and even Ethiopia (in Levantine Arabic the turkey is

dik habash

, “Ethiopian bird”).

As we’ll see, the answer involves Aztec chefs, a confusion between two birds caused by Portuguese government secrecy and, indirectly, the origins of the modern stock exchange. And as with ketchup, it turns out that turkey and other favorite foods traveled around the world to get here, although in this case it’s a round-trip voyage that started with the Native Americans of this hemisphere.

The journey begins thousands of years ago in south-central Mexico. Many different species of wild turkeys still range from the eastern and southern United States down to Mexico, but our domestic turkey comes from only one of these,

Meleagris gallopavo gallopavo

,

the species that Native Americans domesticated

in Michoacán or Puebla sometime between 800

BCE

and 100

CE

.

We don’t know who the turkey domesticators were, but they passed the turkey on to the Aztecs when the Aztecs moved down into the Valley of Mexico from the north. The turkey became important enough to play a role in Aztec mythology, where the jeweled turkey is a manifestation of Tezcatlipoca, the trickster god.

By the fifteenth century, there were vast numbers of domestic turkeys throughout the Aztec world.

Cortés described the streets

set aside for poultry markets in Tenochtitlán (Mexico City), and

8000 turkeys were sold every five days

, all year round, in Tepeyac, just one of several suburban markets of the city.

The words for turkey in Nahuatl, the Aztec language, are

totolin

for turkey hen and

huexolotl

for male turkey.

Huexolotl

gave rise to the modern Mexican Spanish word for turkey,

guajolote

. (English words from Nahuatl include

avocado

,

tomato

,

chocolate

, and

chile.

)

Aztecs and the neighboring peoples made turkey with several different chile sauces. The Nahuatl word for sauce or stew is

molli

, the ancestor of the modern Mexican Spanish word

mole

, and many different moles were made, thick like ketchup or thin like soup, from various kinds of chiles, venison, rabbit, duck, iguana, armadillo, frogs, tomatillos or tomatoes, vegetables like amaranth leaves, and herbs like hoja santa or avocado leaves.

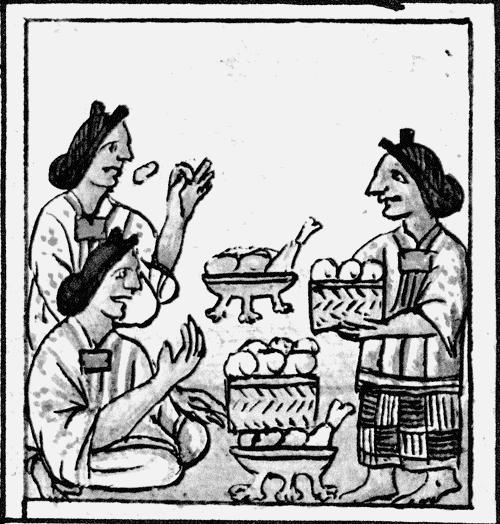

Turkey in stews

and tamales at

the Aztec feast in honor of a newborn child

, from the sixteenth-century illustrations in the Florentine codex

But one of the most common ingredients in

mole

was turkey. Bernardino de Sahagún’s sixteenth-century

General History of the Things of New Spain

tells us that Aztec rulers were served

turkey moles made with chile

, tomatoes, and ground squash seeds (

totolin patzcalmolli

), as well as turkey in yellow chile, turkey in green chile, and turkey tamales. In a

1650 description of a Oaxacan turkey mole

called

totolmole

(from

totolin

[turkey hen], plus

mole

) turkey was stewed in a broth flavored with dried ground chilhuaucle (a black smoky chile still used for Oaxacan mole), pumpkin seeds, and hoja santa or avocado leaves.

The arrival of the Spanish in the New World led to the famous

Columbian exchange of foods between the Old and New worlds. Foods like rice, pork (and hence lard), cheese, onion, garlic, pepper, cinnamon, and sugar all crossed the Atlantic to Mexico, as did Spanish stews like chicken

guisos

with sauteed onion and garlic and Moorish spices like cinnamon, cumin, cloves, anise, and sesame. Soon

recipes for guisos and moles in early Mexican manuscripts

began to merge, mixing chile with European spices and the resulting moles and chil-moles and pipians became a foundation of modern Mexican cuisine.

By the eighteenth or early nineteenth century, recipes appear for dishes like the most famous turkey dish of all,

mole poblano de guajolote

(Turkey with Puebla Mole), for which every chef in Puebla has a recipe. Its most famous ingredient, chocolate, was mainly treated as a drink by the Nahuatl, and doesn’t appear in moles until

an 1817 cookbook, whose recipe for mole de guajolote

(flavored with chile, garlic, onions, vinegar, sugar, cumin, cloves, pepper, and cinnamon) is followed immediately by a recipe for

mole de monjas

(Nuns’ Mole) that adds chocolate and toasted almonds.

Modern recipes are even more spectacular

, including cloves, anise, cinnamon, coriander, sesame, chile, garlic, raisins, almonds, tomatoes or tomatillos, and pumpkin seeds as well as chocolate.

The profusion of ingredients and magical deliciousness of mole poblano de guajolote has led to many myths about the origin of the recipe, delightful folktales about winds blowing spices into mixing bowls, or boxes of chocolate accidentally falling into the pot, or a nun having to create a dish in a hurry for an important visitor from Spain, all quite dramatic but with no basis in truth. Almost all recipes develop not by spontaneous creation but by evolution, as each inventive chef adds a key ingredient or modifies a process here or there. Probably the only grain of truth in these stories is

the role of nuns in convents

, who in Mexico as in Europe probably played an important role in preserving and passing on recipes.

In any case, modern turkey moles, from the simply delicious turkey

mole tamale steamed in banana leaves at La Oaxaqueña down on Mission Street to the phenomenally complex mole poblano de guajolote, are a modern edible symbol of mestizo history, blending ingredients from Christian and Moorish Spain with the turkey, chocolate, and chile of the New World to create an ancient fusion food at the boundaries of the two cultures. Here’s a shortened list of ingredients from Rick Bayless’s recipe:

Ingredients from Rick Bayless’s Recipe

for Mole Poblano de Guajolote

a 10- to 12-pound turkey, cut into pieces

The chiles:

16 medium dried chiles mulatos

5 medium dried chiles anchos

6 dried chiles pasillas

1 canned chile chipotle, seeded

Nuts and seeds:

¼

cup sesame seeds

½

teaspoon coriander seeds

½

cup lard or vegetable oil

heaping

cup unskinned almonds

Flavorings & thickeners:

cup raisins

½

medium onion, sliced

2 cloves garlic, peeled

1 corn tortilla, stale or dried out

2 slices firm white bread, stale or dried out

1 ripe, large tomato, roasted, cored, and peeled

Spices:

3.3-ounce tablet Mexican chocolate, roughly chopped

10 black peppercorns

4 cloves

½

teaspoon aniseed

1 inch cinnamon stick

Salt, about 2 teaspoons

Sugar, about

¼

cup

¼

cup lard or vegetable oil

2

½

quarts poultry broth

The recipe is long, and involves toasting the seeds; frying the chiles and then soaking them in boiling water; frying almonds, raisins, onion, and garlic; frying the tortilla and bread; pureeing the mixture; pureeing the chiles; frying the turkey; frying the sauce; and finally baking the turkey with the sauce.

While mole poblano de guajolote resulted from the east-west direction of the Columbian exchange, the turkey itself (along with corn, squash, pumpkin, beans, potato, sweet potato, tomatoes, chile pepper,

all domesticated in the New World

thousands of years earlier) went to Europe simultaneously in the opposite direction.

The turkey’s trip to Europe

came very quickly after Columbus ate what were probably turkeys on the coast of Honduras in 1502. The Spanish explorers called them

gallopavo

(chicken-peacock), and sent them to Spain by 1512. The spread of turkeys through Europe was astonishingly rapid; by the mid-1500s turkeys were already in England, France, Germany, and Scandinavia.