The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (6 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

In French, the word changed its meaning by the 1930s to mean a light course of eggs or seafood, essentially taking on much of the meaning of earlier terms like hors d’oeuvres or entremets. The change was presumably helped along by the fact that the literal French meaning (“entering, entrance”) was still transparent to French speakers, and perhaps as more speakers began to eat multicourse meals the word attached itself more readily to a first or entering course. So both French and American English retain some aspects of the original meaning of the word; French the “first course” aspect of the meaning (although that had actually died out by 1651) and American the “main meat course” aspect, which has been the main part of its meaning for 500 years.

This shift has a deeper lesson about language change. We are carefully taught to clamp down on changes in language as if new ways of speaking are unnatural, adopted by ignorant speakers out of stupidity or even malice. Yet linguistic research demonstrates that the gradual changes in a language over time often lead to significant improvements in the language’s clarity or efficiency, as happened here with

entrée

. Everyday speakers in both France and America changed the meaning of

entrée

from an obscure third course in an archaic, aristocratic meal

structure to a useful term for an appetizer (in France) or a main course (in America), sensibly ignoring the complaints of the 1938 editors of the

Larousse Gastronomique.

What about the use of entrée now? One of the advantages of the narrow houses and dense neighborhoods of San Francisco is that the restaurants are all very close by, so a short walk down to Mission Street quickly answers that question. I checked all the menus of the 50 restaurants within a few blocks of us (Mexican, Thai, Chinese, Peruvian, Japanese, Indian, Salvadoran, Cambodian, Sardinian, Nepalese, Italian, Jordanian, Lebanese, barbecue, southern, plus the pairwise combinations like Chinese Peruvian roast chicken, Japanese French bakeries, and Indian pizza). The word

entrée

was used only at five restaurants. Not surprisingly these serve mainly European American rather than Asian or Latin American food.

The vast increase in the number of ethnic restaurants and the fading of French words like entrée as a marker of social prestige in the United States are part of a general trend in food, music, and art that

sociologists call

cultural omnivorousness.

Previously high culture was defined solely by a limited number of “legitimate” genres: classical music or opera, or French haute cuisine or wine. The modern high-culture omnivore, however, can be a fan of 1920s blues, or 1950s Cuban mambo, or the ethnic or regional foods championed by writers like Calvin Trillin. High status is signaled now not just by knowing fancy French terms, but also by being able to name all the different kinds of Italian pasta, or appreciating the most authentic ethnic cuisine, or knowing just where to

find the best kind of fish sauce

. Even potato chips are advertised by appealing to this desire to be authentic.

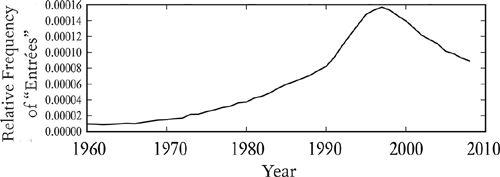

Omnivorousness explains the decline, detailed in the previous chapter, of the use of pseudo-French as a modern marker of status on menus. And omnivorousness is perhaps one reason we are seeing the decline of the word

entrée

in menus and in books and magazines as well. The

Google Ngram corpus

, a very useful online resource that counts the frequency

of words over time in books, magazines, and newspapers, demonstrates entrée’s rise in the 1970s and 1980s and then the fall since 1996:

If entrée is declining in use, what is it being replaced by? Some menus use “main course,” Italian restaurants often use “secondi,” and French restaurants might use “plat.” But the most frequent answer in new restaurants is, Nothing; appetizers and entrées are listed without a label at all, and diners have to figure it out, like the less-is-more implicitness we saw in menus. In the highest-status restaurants, whether the food is an appetizer or entrée portion, how crispy or fluffy it is, or even exactly what you are going to be served can literally go without saying.

Entrée has more to tell us than Alan Davidson guessed: it concisely encapsulates an entire history of culinary status, from the structure of fabulous Renaissance meals, to the early role of French as a signal of high status, to the more recent decline of French as the sole language of culinary prestige, replaced by omnivorousness and by more tacit signals of status.

The high status of French isn’t completely gone, however; Paul and I automatically assumed the French meaning was the “correct” one even though it’s actually the American borrowing that retained entrée’s Renaissance sense of a hearty meat course.

In the next chapter we’ll turn to a word whose change in meaning reflects an even larger social transformation, while still retaining aspects of its meaning that are thousands of years old.

SINCE THE DAYS

WHEN

the native Ohlone people, who caught and ate the bounty of oysters and abalone and crab that thrived throughout the bay, San Francisco has been a good place for seafood. The first restaurants here were mainly Chinese, serving fish caught by the redwood fishing sampans that set out from the

Chinese fishing villages

on the beach south of Rincon Hill. Tadich Grill (founded by Croatian immigrants in 1848) has been using

Croatian methods

of mesquite-grilling fish since the early twentieth century, the Old Clam House has served clam chowder at the foot of Bernal Hill since 1861 when it was still waterfront property with a plank road to downtown, and Dungeness crab has been in demand for San Francisco Italian Thanksgivings and Christmas Eve cioppinos since the nineteenth century.

And then there’s ceviche (or seviche or cebiche), the tangy fish or seafood marinated in lime and onion that’s the official national dish of Peru, a gift to San Francisco from the Peruvians who also brought the Pisco that made Pisco punch. Peruvians have been in San Francisco since the 1850s, when what’s now called Jackson Square at the southern foot of Telegraph Hill was called Little Chile and was filled with the Chileans, Peruvians, and Sonorans drawn by the gold rush. This was before the transcontinental railway was built, so ships from Valparaiso and Lima brought the earliest men to the gold fields.

Chilean and Peruvian miners introduced techniques

like dry digging

and the “chili mill” that they had learned in the great silver mines of the Andes, the mines that produced the Spanish silver dollar or “piece of eight” that was the first world currency. Now San Francisco has so many cevicherias that I have found myself in many a pleasant debate about which is best, from cozy gems in the neighborhoods to bright whitewashed dining rooms overlooking the water.

What is ceviche? The Royal Spanish Academy’s

Diccionario de la lengua española

defines

cebiche

as:

Plato de pescado o marisco crudo cortado en trozos pequeños y preparado en un adobo de jugo de limón o naranja agria, cebolla picada, sal y ají.

[A dish of raw fish or seafood diced and prepared in a marinade of lime or sour orange juice, diced onion, salt and chile.]

In Peru, ceviche is often made with

aji amarillo

(Peruvian yellow chile), and served with corn and potatoes or sweet potatoes.

Ceviche turns out to have a historical link to the seafood dishes of many nations, from fish and chips in Britain to tempura in Japan to escabeche in Spain. All of them, as well as some others that we’ll get to, turn out to be immigrants themselves, and descend directly from the favorite dish of the Shahs of Persia more than 1500 years ago.

The story starts in the mid-sixth century in Persia. Khosrau I Anushirvan (501–579

CE

) was the Shahanshah (“king of kings”) of the Sassanid Persian empire, which stretched from present-day Armenia, Turkey, and Syria in the west, through Iran and Iraq to parts of Pakistan in the east. This was an extraordinary period of Persian civilization. The capital, Ctesiphon, on the banks of the Tigris in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq; ancient Babylonia), was perhaps the largest city in the world at the time, famous for its murals and a center of music, poetry, and art. Although the state religion was strictly Zoroastrian, Jewish scholars wrote the Talmud here, Plato and Aristotle were translated into Persian, and the rules for backgammon were first written down.

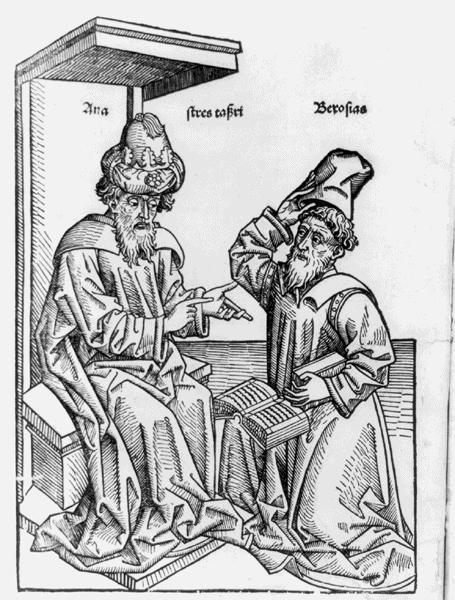

King Khosrau and Borz

ya the scholar, from the 1483 German rendering

Das buch der weißhait

of John of Caput’s Latin translation of the

Panchatantra

This part of the Fertile Crescent was irrigated by

an extensive canal system

that was significantly extended by Khosrau.

Persia was at the center of the global economy

, exporting its own pearls and textiles, and helping bring Chinese paper and silk and Indian spices and the Indian game of chess to Europe.

Another borrowing from India in Khosrau’s time was the

Panchatantra

, a collection of c. 200

BCE

Sanskrit animal fables that the Persian physician Borz ya brought back and translated into Persian, and which was the source of stories in

ya brought back and translated into Persian, and which was the source of stories in

One Thousand and One Nights

and Western nursery tales like the French fables of Jean de La Fontaine. There is a beautiful fable about Borz ya’s trip itself, told in the Persian national epic “The Shahnameh,” in which Borz

ya’s trip itself, told in the Persian national epic “The Shahnameh,” in which Borz ya asks King Khosrau for permission to travel to India to acquire an herb from a magic mountain that when sprinkled over a corpse could raise the dead. But when he arrives in India a sage reveals to him that the corpse is “ignorance,” the herb is “words,” and the mountain was “knowledge.” Ignorance can only be cured by words in books, so Borz

ya asks King Khosrau for permission to travel to India to acquire an herb from a magic mountain that when sprinkled over a corpse could raise the dead. But when he arrives in India a sage reveals to him that the corpse is “ignorance,” the herb is “words,” and the mountain was “knowledge.” Ignorance can only be cured by words in books, so Borz ya brings back the

ya brings back the

Panchatantra

.

j to Fish and Chips

j to Fish and Chips