The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (5 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

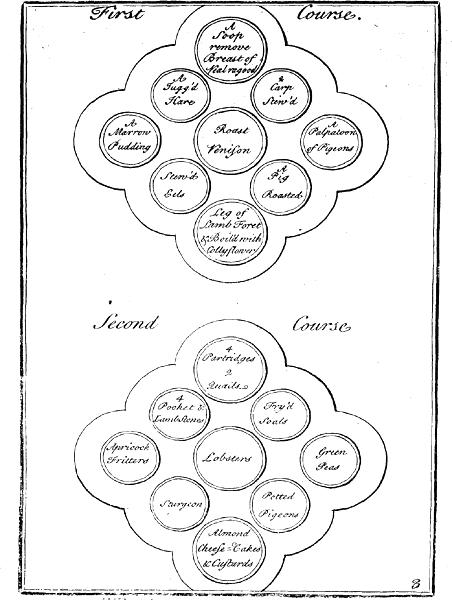

By a hundred years later, in the eighteenth century, the French, English (and colonial American) banquet meal had standardized in a tradition called

à la Française

or sometimes

à l’Anglaise

. Meals were often in two courses, each course consisting of an entire tableful of food. All the offerings were laid out on the table, with the most important in the middle and the soup or fish perhaps at the head of the table, entrées scattered about, and the smallest courses (the

hors d’oeuvres

, literally “outside the main work”) placed around the edges (that is, “outside” of the main stuff).

After the soup was eaten, it was taken away and replaced on the table by another dish, called the

relevé

in French or the

remove

in English. A remove might be a fish, a joint, or a dish of veal. The other dishes (the entrées and entremets) stayed on the table. Sometimes a fish course was itself removed, just like the soup. Then the joint might be carved

while the entrees and hors d’oeuvres were passed around. After this first course was completed, the dishes would all be cleared away and a second course would be brought in, based around the roast, usually hare or various fowl such as turkey, partridge, or chicken, together with other dishes.

The figure opposite shows how the dishes were laid on the table in the two courses or servings à la Française from the first cookbook published in the American colonies, Eliza Smith’s very popular English cookbook

The Compleat Housewife

: or, Accomplished Gentlewoman’s Companion

, first published in 1727 in England, and published in the American colonies in the 1742 edition.

Note the “soop,” with the Breast of Veal “ragood” remove, and the entrées like Leg of Lamb, 2 Carp Stew’d, and A Pig Roasted. Recall that the classic French roast course consisted of roast fowl; that would be the 4 Partridges and 2 Quails in the second course; roast beef and pork were served in the first course as entrées or removes. Also note that at this point, the word

entrée

was not yet used in English; at least it’s not mentioned in Eliza Smith, and the first usage listed in the

Oxford English Dictionary

is decades later, in William Verral’s 1759

A Complete System of Cookery

, where it is marked in italics as

a newly borrowed foreign word

.

The next change in the ordering of meals was another hundred years later, in the nineteenth century, to a method known as service

à la Russe

, significantly closer to modern coursed dinners. Instead of the food being all piled on the table to get cold, dishes are brought in one course at a time on plates served directly to the guests. Thus, for example, meat is carved at the sideboard or the kitchen by servants rather than by the host at the table. Since the table was no longer covered in food, it was decorated with flowers and so on. And since the guests couldn’t know what food they were going to eat just by looking at the table, a small list of dishes was placed by each setting. The name for this list was borrowed (first in French and then English) from a shortening of the Latin word

min tus

tus

, “small, finely divided, or detailed.”

It was called a

menu

.

Placement of dishes in the two courses, from Eliza Smith’s 1758

The Compleat Housewife

(16th edition)

This service à la Russe took over in France in the nineteenth century; in England and the US the custom shifted roughly between 1850 and 1890, and our modern meals are now served in serial courses à la Russe. We still maintain remnants in the US of the old-fashioned method of putting all the food on the table at once and having the host carve at the table, in very traditional meals like Thanksgiving dinner. (Thanksgiving is archaic in all other aspects as well, but we'll come back to that.)

By the nineteenth century the

hors d’oeuvres began to be served earlier

, even before the soup. So at this point (meaning the second half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth), the order of a traditional meal was something like the following:

1. Hors d’oeuvres

2. Soup

3. Fish (possibly followed by a remove)

4. Entrée

5. Break (sherbet, rum, absinthe, or punch)

6. Roast

7. Possible other courses (salads, etc.)

8. Dessert

The word

entrée

maintained this meaning of a substantial meat course served after the soup/fish and before the roast in Britain, France, and America until well after the First World War. The

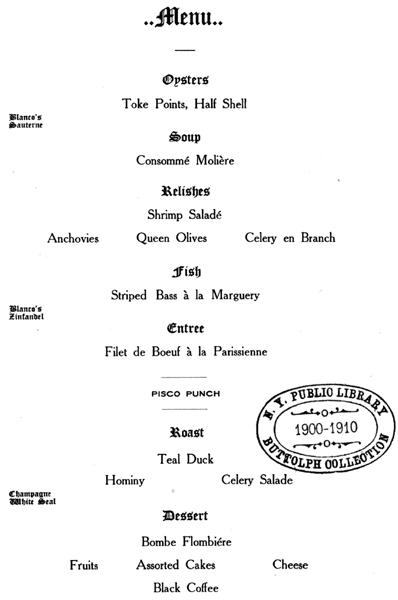

menu opposite is from 1907

from

the newly built Blanco’s

, the legendary O’Farrell Street restaurant and bordello whose fantastic marble columns and rococo balconies were the site of the unbridled drinking, gambling, whoring, and general bad behavior that characterized San Francisco’s Barbary Coast days but also symbolized the city’s rise from the ashes of the 1906 earthquake. Blanco’s later became the Music Box, the burlesque owned by San Francisco’s

beloved fan dancer Sally Rand

. It’s now the Great American

Music Hall, one of the most beautiful concert venues in the city, but if you go around to the back alley you can still see the faded Blanco’s sign painted on the brick. Notice on the menu some of the pseudo-French we talked about in the previous chapter (“Celery en Branch,” the misspelling of “Parisienne,” and some unexpected accents).

Menu from Blanco’s Restaurant, San Francisco, 1907

As for the Pisco punch that separates the entrée from the roast, it was San Francisco’s signature drink in the nineteenth century. The punch was made from Pisco brandy, lemon juice, and pineapple syrup, and was an “

insidious concoction

which in its time had caused the unseating of South American governments and women to set world’s records in various and interesting fields of activity,” as cocktail historian David Wondrich recounts from a later memoir. Pisco punch was popularized and maybe even invented

here at the old Bank Exchange

at the corner of Montgomery and Washington, which made it through the earthquake of ’06 only to be replaced by the Transamerica Pyramid.

By 30 years later, the word

entrée

has expanded a bit in meaning. In US menus from the 1930s, the word is still used in its classic sense as a substantial “made” meat dish distinguished from roasts, but by now sometimes the term includes fish, and has lost the sense of a course in a particular order.

After the war, as separate roast and fish courses dropped out of common usage, the word

entrée

expanded once again to signify any main course. A 1946 menu from the “World Famous Cliff House,” perched on the cliffs at Land’s End overlooking the Pacific, refers to all main courses, including “Grilled Fillet of Sea Bass, Parsley Butter” as entrees. (The Cliff House is still there, but now the waves crash over the ruins of the Sutro Baths below, originally built by millionaire populist Adolph Sutro in 1896 with vast swimming pools fed by the ocean. In the romantic foggy midnights of my youth, we used to sneak around those ruins and through the long dark tunnels that run into the cliff.) By 1956

entrée

came to be used even when there is no meat at all; that year in fact

Alioto’s on Fisherman’s Wharf

offered “Fish Dinners” consisting of Crab Cocktail, Soup or Salad, Entree, and Dessert.

American meals by the 1950s thus standardized on the modern three-course meal consisting of appetizer, entrée, and dessert, perhaps augmented by a salad or soup.

What about in France? The French use of the word

entrée

in Escoffier’s

1921

Le Guide Culinaire

was still the traditional one (“made” hot meat dishes served in the classic sequence before a roast). Escoffier classifies as entrées almost any meat or poultry dish that we would now consider a main course: steaks (entrecotes or filet de boeuf, tournedos), cassoulet, lamb or veal cutlets, ham, sausage, braised leg of lamb (gigot), stews or sautes of chicken, pigeon or turkey, braised goose, foie gras. Escoffier has over 500 pages of entrée recipes. Only roast fowl and small game animals are classified as roasts, in a

small 14-paged roast section

.

Thus, the change from the classic central heavy meat entrée to the modern light first course must have come after 1921 in France but before 1962, by which point the recipes Julia Child gives for entrées are light dishes, mainly quiches, soufflés, and quenelles. We see similar light dishes listed as typical entrées in

the modern

Larousse Gastronomique

, the French culinary encyclopedia.

Actually, an

older

edition of the

Larousse Gastronomique

—the very first one from 1938, in fact—gives us even more insight in its definition of entrée:

Ce mot ne signifie pas du tout

, comme bien des personnes semblent le croire, le

premier

plat d’un menu. L’entrée est le mets qui suit, dan l’ordonnance d’un repas, le plat qui est désigneé sous le nom de relevé, plat qui, lui-même, est servi après le poisson (ou le mets en tenant lieu) et qui, par conséquent, vient en troisième ligne sur le menu.

[This word does not mean, as many seem to believe, the

first

dish in a meal. In the ordering of a meal, the entrée is the dish that follows the relevé, the dish served after the fish (or after the dish that takes the place of the fish) and, therefore, comes third in the meal.]

What we have here is a “language maven” complaining about a change in the language. (

Aux armes!

The French masses are using the word

entrée

incorrectly!) Language mavens have probably been around pretty much since there were two speakers to complain about the

vocabulary, pronunciation, or grammar of a third. They can be very useful for historical linguists, because grammar writers don’t complain about a change in the language until it’s already been widely adopted. So we can be pretty certain that in popular usage,

entrée

mostly meant “first course” in French by 1938.

So, to review: The word

entrée

originally (in 1555) meant the opening course of a meal, one consisting of substantial hot “made” meat dishes, usually with a sauce, and then evolved to mean the same kind of dishes but served as a third course after a soup and a fish, and before a roast fowl course. American usage kept this sense of a substantial meat course, and as distinct roast and fish courses dropped away from common usage, the meaning of

entrée

in American English was no longer opposed to fish or roast dishes, leaving the entrée as the single main course.