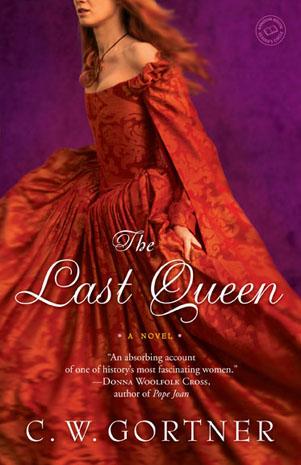

The Last Queen

Authors: C.W. Gortner

To my mother, Miravillas Blanco,

and to my late father, Willis Always Gortner II;

For Spain, a lifelong infatuation with books,

and the courage to persevere

.

.

.

And to Erik, for always believing

THE LAST QUEEN

C.W. GORTNER

――――――――――――――――――――――――

Tordesillas, 1550

Midnight has become my favorite hour.

The sounds of the night are less intrusive, the shadows like a familiar embrace. By the light of a

single candle, my world seems march larger than it is, as large as it once was. I suppose it is the bane

of morality to suffer time as it narrows and confines, to know that never again will anything seem as

wide, as open, as unattainable as it did in our youth.

I have had more occasion than most to reflect on the passage of the years. But it is only now, in

this quiet hour, when al those who surround me have surrendered to sleep, that I can see clearly,. It is

a consolation, the knowledge, a gift I do not wish to squander on recrimination or vain regret. History

may not forgive, but I must.

Hence, this blank page, the sharpened feather and the pot of ink, My hand does not tremble as

much, my legs do not pain me so that I cannot sit in this grand, if somewhat frayed, chair. The

memories tonight are vivid, not evanescent; they evoke and entice. They do not haunt. If I close my

eyes, I can smell the smoke and jasmine, the fire and rose; I can see the vermillion walls of my beloved

palace, mirrored in a child’s eyes,. Thus did it begin, all of it, in the fal of Grenada.

And so tonight, I will bear witness to the past, I will inscribe everything I have lived and seen,

everything I have done, every secret I have hidden.

I will remember, because a queen can never forget.

__________________________________

1492 ― 1500

INFANTA

PRINCES DO NOT MARRY FOR LOVE.

―

GATTINARA

__________________________________

was thirteen years old when my parents conquered Granada. It was 1492, the

year of miracles, when three hundred years of Moorish supremacy fell to the

I might of our armies, and the fractured kingdoms of Spain were united at last.

I had been on crusade since my birth. Indeed, I‟d often been told of how the

pangs had overcome my mother as she prepared to join my father on siege, forcing

her to take to her childbed in Toledo― an unseemly interruption she did not relish,

for within hours she had entrusted me to a nursemaid and resumed her battles.

Together with my brother, Juan, and my three sisters, I had always known the chaos

of a peripatetic court, which shifted according to the demands of the Reconquest, the

crusade against the Moors. I slept and awoke to the deafening clamor of thousands of

souls in armor; to beasts of burden dragging catapults, siege towers, and primitive

cannon; to endless carts piled with clothing, furnishings, supplies and utensils. Rarely

had I enjoyed the feel of marble underfoot or eaves overhead. Life consisted of a

series of pavilions staked on stony ground, of anxious tutors gabbling lessons and

cringing as flaming arrows whooshed overhead and crashing boulders decimated a

stronghold in the distance.

The conquest of Granada changed everything― for me and for Spain., That

covered mountain citadel was the most opulent jewel in the Moor‟s vanishing world;

and my parents, Isabel and Fernando, their Catholic Majesties of Castile and Aragón

vowed to reduce to rubble rather than suffer the heretics‟ continuing defiance.

I can still see it as if I were standing at the pavilion entrance: the lines of soldiers

flanking the road, winter sunlight sparking off their battered breastplates and lances,.

They stood as if they had never known hardship, gaunt faces lined, forgetting in that

moment the countless privations and countless dread of these ten long years of battle.

A thrill ran through me. From the safety of the hilltop where our tents were, I had

watched Granada fall. I followed the trajectory of the tar-soaked flaming stones

hurled into the city walls and beheld the digging of trenches filled with poisonous

water so no one could breach them. Sometimes, when the wind blew just right I even

heard the moans of the wounded and the dying. At night while the city smoldered, an

eerie interplay of shadow and light shivered across the pavilion‟s cloth walls, and we

awoke every morning to find cinder dust on our faces, our pillows, our plates―

everything we ate or touched.

I could scarcely believe it was over. Turning back inside, I saw with a scowl that

my sisters still struggled with their raiment. I had been the first to wake and down the

new scarlet brocades my mother had ordered for us. I stood tapping my feet, as our

duenna, Doña Ana, shook out the opaque silk veils we always had to wear in public.

“A curse on this dust,” she said. “It has seeped even into the linen. Oh, but I

cannot wait for the hour when this war is at an end.”

I laughed. “That hour has come! Today Boabdil surrenders the keys to the city.

Mamá already awaits us on the field and―” I paused. “By the saints, Isabella, surely

you don‟t plan to wear mourning today of all days?”

From under her black coif my elder sister‟s blue eyes flared. “What do you, a mere

child, know of my grief? To lose a husband is the worst tragedy a woman can endure.

I will never stop mourning my beloved Alfonso.”

Isabella had a flare for the dramatic, and I refused to let her get away with it. “You

were married less than six months to your beloved prince before he fell off a horse

and broke his neck. You only say that because Mamá has mentioned betrothing you

to his cousin― if you ever stop acting the bereaved widow, that is.”

Prim Maria, a year younger than I and possessed of a humorless maturity,

interposed himself. “Juana, please. You must show Isabella respect.”

I gave a toss of my head. “Let her first show respect for Spain. What will Boabdil

think when he sees an infanta of Castile dressed like a crow?”

Doña Ana snapped, “Boabdil is a heretic. His opinion is of no account.” She

thrust a veil into my hands. “Cease your chatter and go help Catalina.”

Sour as curdled cheese our duenna was, though I supposed I should have spared a

thought for the trials the crusade had wrought on her aged bones. I went to my

youngest sister Catalina. Like Isabella, our brother, Juan, and, to some extent Maria,

Catalina resembled our mother; plump and short, with beautiful pale skin and fair

hair, and eyes the color of the sea.

“You look lovely,” I told her, tucking the scalloped veil about her face. Little

Catalina whispered in return, “So do you.

Eres la más bonita

.”

I smiled . Catalina was right. She had yet to master the art of the compliment. She

couldn‟t have known her words eased my awareness that I was unique among my

siblings. I had inherited my looks from my father‟s side of the family, down to the

slight cast in one of my amber eyes and unfashionable olive complexion. I was also

the tallest of my sisters, and the only one with a mass of curling coppery hair.

“No, you‟re the prettiest,” I said and I kissed Catalina‟s cheek, taking her hand in

mine as the distant blast of trumpets sounded

Doña Ana motioned. “Quick! Her Majesty waits.”

Together, we went to a wide charred field where a canopied dais had been

erected.

My mother stood clad in her high-necked mauve robe, a diadem encircling her

caul. As always in her presence, I found myself bending my knees slightly to conceal

my budding height

“Ah.” She waved a ringed hand. “Come. Isabella and Juana, you stand to my right,

Maria and Catalina to my left. You are late. I was beginning to worry.”

“Forgive us, Your Majesty,” said Doña Ana, with a deep reverence. “There was

dust in the coffers. I had to air their Highness‟ gowns and veils.

My mother surveyed us. “They look splendid.” A frown creased her brow.

“Isabella,

hija mia

, black again?” She shifted her regard to me. “Juana, stand up straight.”

As I did her bidding, another trumpet blast reached us, much closer now. My

mother ascended the dais to her throne. The cavalcade of

grandes,

the high lords and nobles of Spain, materialized on the road in a fluttering of standards. I wanted to

shout in excitement. My father rode at their head, his black doublet and signature red

cape accentuating his broad shoulders. His Andalucían destrier pranced beneath him,

caparisoned in Aragón‟s scarlet and gold colors. Behind him rode my brother, Juan,

his white-gold hair tousled about his flushed, thin face.

Their appearance elicited spontaneous cheers from the soldiers.

“Vive el infante!”

cried the men, beating their swords against shields.

“Vive el rey!”

The solemn churchmen followed. Not until they reached the field did I catch

sight of the prisoner in their midst. The men drew back. My father motioned, and the

man on the donkey was made to dismount and forced forward, to raucous laughter.

He stumbled.

My breath caught at my throat. His feet were bare, bloodied, but I marked his

inherent regality as he unwound his soiled turban and cast it aside, revealing dark hair

that tumbled to his shoulders. He was not what I expected, not the heretic caliph

who‟d haunted our dreams, whose hordes had poured boiling pitch and shot fiery

arrows from Granada‟s ramparts against our enemy. He was tall and lean, with bronze

skin. He might have been a Castilian lord as he crossed the field to where my mother

waited, his steps measured, as if he crossed an audience hall clad in finery. When he

fell to his knees before her throne, I caught a glimpse of his weary emerald eyes.

Boabdil lowered his head. From his neck, he removed an iron key on a gold chain

and set it at my mother‟s feet, a symbolic symbol of defeat.

Jeering applause and insults came from the ranks. With an impassive countenance

that conveyed both his inviolate distain and infinite despair, Boabdil allowed the

applause to fade before he lifted his practiced plea for tolerance. When he finished, he

waited, as did everyone present, all eyes fixed on the queen.

My mother stood. Despite her short stature, slackened skin, and permanently

shadowed eyes, her voice carried across the field imbued with the authority of the

ruler of Castile.

“I have heard this plea and accept the Moor‟s submission with humble grace. I‟ve

no desire to inflict further suffering on him or his people. They‟ve fought bravely, and

in reward I offer all those who convert to the True Faith baptism and acceptance into

our Holy Church. Those who do not will be granted safe passage to Africa―

providing they never return to Spain again.”

My heart skipped a beat when I saw Boabdil flinch. In that instant, I understood.

This was worse than a death sentence. He‟d surrendered Granada, thus bringing an

end to centuries of Moorish dominion in Spain. He had failed to defend his citadel

and now craved an honorable death. Instead, he was to be vanquished, to bear

humiliation and exile till the end of his days.

I looked at my mother, marked the satisfaction in the hard set of her lips. She