The Last Speakers (21 page)

Authors: K. David Harrison

The Internet is full of ads for mind tools that claim to improve memory. They promise enhanced ability to recite long numbers, connect names and faces, and do mentally onerous tasks. People work on sudoku puzzles for their touted cognitive benefits. Yet even with enhanced capacity and all the technologies to support us, we are flooded with information we cannot retain. Memory deteriorates across our life span, and we do not always manage to transmit crucial facts to the next generation.

Indigenous cultures, with their millennia of intense memorization, have successfully solved the information-to-memory problem many times over. They've managed to retain, transmit, and distribute vast bodies of knowledgeâfor example, the knowledge of thousands of medicinal plants possessed by the Kallawaya people. They've done so mentally, without the aid of writing or recording devices. What are their secrets? How do people in these societies distribute knowledge? How do they recruit entire social networks of people to act like a giant parallel processor, storing and sharing complementary bits of information? Some of the answers can be found in the ancient stories that people still tell in places like Siberia.

GIRL-HERO AND THE SIBERIAN BARD

I arrived in the dusty Siberian village of Aryg-Ãzüü on a hot August day in 1998, looking for a splendidly talented Tuvan orator I'd heard rumors of. I found Shoydak-ool, a vigorous, cheerful man in his late 70s, living in a small log house with his wife and a dog and a milk cow out in the shed. Shoydak had retired from driving a combine on a collective farm to practice his avocationâstorytelling. In recent years, opportunities had become scarce. “People are not interested in the old stories,” he remarked. “Our kids just want to watch Jackie Chan movies nowadays.” Not an inappropriate analogy, I thought to myself: heroes of Tuvan myths often represent the same archetypal character found so often in Hong Kong action flicks.

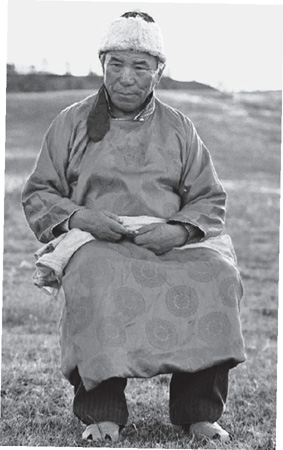

Shoydak-ool Khovalyg, Tuvan epic storyteller

Shoydak-ool refused to tell his story without a proper audience, so we set out at seven o'clock the next morning to visit the nomadic summer camp of his relatives. He roused the family out of bed by announcing loudly: “I'm here to tell you a story.”

Once morning chores were completed and some milky, salty tea boiled, Shoydak-ool donned a bright pink robe with a sash and a red, pointed, Santa Clausâlike hat. Taking a wooden ceremonial spoon, he sprinkled tea as an offering to the spirits. Then he began his story, and it was a real cliff-hanger.

In Shoydak-ool's story, a girl-hero, Bora, lacks any obvious advantages or clear goal in life, but possesses wit, persistence, and strength of character. These traits are tested as she sets off on a quest to vanquish evil forces and revive her dead brother. Along the way, she suffers moments of self-doubt and receives sage advice from her clever talking horse. She must use magical powers, perform feats of strength, disguise her sex, and change her shape to become a rabbit. The horse advises her that she must win the hand of a magical princess in marriage. To do so, Bora disguises herself as a man. Her horse helps her perfect the disguise by gluing bear fur over her breasts and attaching a goose's head as a fake penis. Now passing as a (somewhat freakish) man, Bora dominates the archery, wrestling, and horse-racing competitions.

To give readers the flavor of this tale, here is the passage describing the wrestling match, when four fighters attack the heroine. In a scene reminiscent of the World Wrestling Federation, Bora dispatches each opponent with animal-inspired agility and acrobatics.

A

fairly

strong wrestler came up,

flapping

his arms in an eagle dance.

Bora

knocked

him with the speed of a

kine

,

and

dropped

him upside down on

top

of his head.

Then another

super

strong wrestler

strutted

up to her.

Bora

gripped

his ankle with the courage of an

eagle

,

flipped

him over her shoulder, and

flung

him down.

Then a

really

strong wrestler

ran

up to her.

Bora

flew

toward him with the agility of a

falcon

,

and laid him

flat

in a

flash

.

Another

fairly

strong wrestler

feinted

, to

frighten

her.

Bora

hopped

between his legs with the agility of a

hare

,

and

tackled

him painfully on his

tailbone

on bare ground.

In the end, Bora wins the hand of the princess, who uses magic to revive the dead brother. The princess marries the brother, Bora changes back into a girl and marries her own suitor, and they live happily on the high grassy plains herding sheep and camels.

4

The memory secrets that I found in the Bora story were so deep that the storyteller himself was not aware of their existence. Even though he relied on complex sound structures to fix the lines in his memory, he had no ability to describe or explain them. A corollary would be the ancient Nazca lines in Peru. These gigantic drawings of animals were etched into vast expanses of the desert. The paradox is that these fanciful figures, hummingbirds and jaguars, can be viewed only from high up in the air, a vantage point never available to the lowly desert diggers. They created gargantuan works of art, without ever seeing them as a whole.

In the Bora tale, vast, extended patterns stretch across hundreds of lines. These mathematically exact repetitions of certain sounds are not perceptible to the individual storyteller. Unless he or she were to set the entire tale down on paper and then tabulate all the examples of certain vowels and consonants across the many pages, the storyteller would remain unaware that the pattern even existed. For example, in the wrestling passage above, the reader will have noticed that each line has some words in italics. In the original Tuvan, but not in English, all the words in italics within each stanza begin with the same sound. For example, in stanza 1, the words “fairly,” “flapping,” “knocked,” “kine” (a type of bird), “dropped,” and “top” all begin with a “d” sound in Tuvan. This creates a strong cluster of alliteration, making the passage more dramatic for listeners and more memorable for the tale-teller. The second, third, and fourth stanzas do the same, but with different sounds. For a full 12 lines, we get a barrage of alliterative gut punches to make the fight scene come alive. And this is just one small passage! Similar patterns play out across the entire epic. No one author composed the tale, and each teller was free to make his own changes. Yet the structure emerged over countless tellings as a solid, intricate framework, aiding memorization and shaping the tale into a grand work of verbal art.

As Shoydak-ool told his tale, the family greeted the ribald parts with laughter and the suspenseful parts with anticipation. This entire family of nomads, ages 7 to 75, and I, an American linguist, were together experiencing something quite rare. Most Tuvans have never heard a traditional epic performed live. What made this encounter even more poignant was a feeling that such stories could soon be lost to history. I was determined to wrest every bit of meaning from this story, and to bring it to a wide audience.

Coming back from the plains of Siberia to the ivory tower of Yale was quite a shock. I had a little basement office where I would spend hours poring over my field notes and transcribing my recordings. The Post-it note became my best friend, and I tabulated and cross-indexed my hundreds of pages of notes in a very low-tech way. While some linguists key all their data into a sophisticated relational database, I was a bit of a Luddite, preferring the serendipitous connections to the powered search queries. Bit by bit, in my basement corner, I put together the pieces of an immense puzzle of the sounds and structures of Tuvan, hoping that some sense, some pattern, would emerge. Writing a dissertation (“dissertating,” as graduate students like to say) is a lonely business and puts a real crimp in your social life. The light at the end of the tunnel came in the form of careful comments on the margins contributed by the three professors on my thesis committeeâ¦and I was grateful for every little typo or large theoretical issue they pointed out. Many students get bogged down and never finish their thesis, and so I was particularly grateful for the advice: “There are two types of dissertations: brilliant ones and finished ones.” I aimed for the latter type, and still managed to make a few discoveries along the way.

One element in the grammar of Tuvan really excited me, and I'll share it here in a nontechnical way. This was

vowel harmony,

a Zen-sounding phenomenon but actually a concept that might excite mathematicians more than Buddhists. Vowel harmony is a kind of statistical perfection, a strictly regulated pattern that shapes the way speakers speak in a language. Just as a sonnet must be precisely 14 lines and a haiku seven syllables (depending on who's counting), vowel harmony is a stringent template for an entire language, governing how sounds are arranged.

Tuvans have eight vowels to choose from (in English, we have between 12 and 14 vowels, depending on the dialect one speaks, even though we have just 5 symbols for writing vowels). From this set of eight vowels, they can use only half of them in any given word. Vowels “harmonize,” meaning that certain vowels repel each other and thus can never ever appear in the same word, while other vowels attract each other. So a word as simple as

inu

or

emo

is simply impossible for a Tuvan to pronounce or perceive, given the filter imposed by vowel harmony, because

i

and

u

belong to different vowel classes, as do

e

and

o

. Meanwhile, words like

ona

or

edi

are perfectly harmonicâthough they are not real words of Tuvan, they could be easily perceived and pronounced by a Tuvan speaker. A great deal of scientific study has been conducted on vowel harmony languages, such as Finnish, Hungarian, and Manchu, but Tuvan was a relatively little-studied example, and its system proved to be very complex and novel to science. So as I sat in my basement office, manipulating symbols on the page, I had a sense that a new discovery was being made. Just as when you examine snowflakesâthough no two are identical, you may discern some basic patternsâI was delighted to pull tiny sound patterns out of an entire landscape of speech and display them in the pages of my dissertation.

Dissertations tend to go their way to a dusty death, and so I was amused recently when I opened a copy of my circa 2000 vintage writings and found them utterly obscure to me. Did I really write this? I wondered. And if I did, what possible contribution did it make if even I, the author, can scarcely interpret it ten years on? My wise professor had advised me that if I wanted my work to have a longer shelf life, I should stick to the descriptive facts. A certain amount of linguistic theory did have to be mixed in, because that is what the culture of science demands, but I viewed the theory part as the proverbial curl in the pig's tail. I do not value it much now, nor do I think it made any lasting impact. My factual descriptions of Tuvan sound structure, on the other hand, led to many practical projects such as the online talking dictionary of Tuvan, the iPhone Tuvan talking dictionary application, and a printed TuvanâEnglish dictionary that was distributed free to schools in Tuva to help Tuvan kids master English. All of this may seem like a long departure from Shoydak-ool, but I would like to think that my contributions will help maintain the ancient art of Tuvan storytelling for many speakers to come.

ALTERNATIVE CREATION MYTHS

In 2005, I began working in India with peoples known as “tribals,” who reside below the bottom of India's socially rigid caste system. I was lucky that Greg Anderson, whom I had worked with for years in Siberia, persuaded me that a change of language and climate might inspire us. And so we set off to investigate what Greg had described as “some of the craziest” languages on Earth. Greg, being the scholar he is, had digested every bit of published literature that existed on these languages. For me, it was to be a sudden baptism into a whole new type of language, and a feast of complex words.

In Orissa state, on the Bay of Bengal, we met members of the Ho community, who have a distinct language and culture. Numbering perhaps as few as one million (small, in the context of the billion-plus Indian population), the Ho live as a scattered diaspora across portions of eastern India. Their ancestors settled here long before the arrival of the Aryan and Dravidian peoples who now dominate them. To this day, the Ho and other tribals are referred to as

adivasi,

India's first peoples.