Authors: K. David Harrison

The Last Speakers (22 page)

While in India, I heard many stories that stuck in my mind. One self-taught scholar I met, K. C. Naik Biruli of the Ho people, did not fit the image popular in India's press of an uncivilized tribal. Neatly dressed and speaking fluent English, K. C. narrated for us an ancient Ho creation story in his own tongue, then expertly translated it into English. He also demonstrated the Ho alphabet, a spectacularly bizarre writing system that has not yet gained wide use among his people nor been accepted into worldwide technology for writing on computers.

5

Thus even when the Ho language is written down, it is written mostly by hand. Happily, this means Ho stories must be passed on almost solely by word of mouth, infusing them with vitality.

Few cultures I have encountered celebrate and revere the spoken word as deeply as the Ho people do. Their word

kaji

means “to say” or “to speak,” but it also means “language” and “word,” as well as “to scold.” Kaji is wonderfully flexible, combining into more than 150 words describing what you can make happen through speech, or what linguists call “speech acts.” The basic idea of speech acts is that words are not just ephemeral sounds conveying meaning. They can also perform actions in the real world, just like a hammer, a pen, or a hand. The classic example is the statement “I now pronounce you man and wife.” The words themselves, apart from their meaning, actually make something happen in the world: Two people are married by the force of that particular speech act (provided, of course, that the person making the statement is authorized to do so).

The Ho language builds upon kaji to express more than 150 acts that you can perform by speaking. Peeking into the marvelous Ho dictionary written by Jesuit scholar Father John Deeney, we find many amusing examples, mostly describing unkind speech behaviors:

kaji-ker | to tell another's faults |

kaji-boro | to scare or intimidate by verbal threats |

kaji-giyu | to shame or embarrass someone by one's words |

kaji-pe | to strengthen or encourage someone by one's words |

kaji-rasa | to bring joy by one's words |

kaji-topa | to try to cover up one's mistakes or defects by one's words |

kaji-ayer | to tell beforehand, to prophesy |

kaji-koton | to say something that obstructs, for example, an arrangement for a marriage or a preparation for a feast |

Clearly, the Ho are acutely aware of the power of words to discomfit and blame. The profusion of kaji expressions admonishes Ho speakers to choose words carefully so as not to inflict harm. Otherwise their hearers, by using kaji words, will be able to efficiently describe and report what they have done, thus assigning responsibility for many types of negative speech. These concepts can all be expressed in English, too, and it's fun to think of one-word equivalents in addition to the ones given above, so here goes: to bad-mouth, to harass, to shame, to hearten, to exhilarate, to foretell, to backpedal.

The Ho vocabulary, as sampled in Deeney's dictionary, is truly a bottomless well of knowledge about Earth, humans, the acoustic environment, social relations, hunting, plants, myth, history, and all manner of technologies. One choice entry found on the very first pageâpertaining to silkworm cultivationâwill suffice to show the expressive power and rich information capacity of a single Ho word:

aasar

âA bow and arrow; to make in the form of a bow, e.g., the rope stretched across the two ends of an arched stick of the

tiril

tree to which rope silkworm cocoons are attached when it is almost time for the moth to emerge; to attach silkworm cocoons to this.

7

Readers are urged to browse Deeney's Ho dictionary, or any other well-written and ethnographically informed dictionary, to fully experience the efficiency of information packaging that can be found in vocabulary.

On a more positive note, the Ho celebrate the power of language to charm, regale, and entertain. They devote enormous efforts to telling, memorizing, and retelling their myths, many of which have never been written down, recorded, or translated. Over endless cups of cardamom tea, K. C. narrated a radical alternative creation myth. As the Ho like to tell it, drunkenness, sexuality, and shame are God's gift to the first man and woman. These behaviors, divinely instigated, led humans to reproduce and populate the Earth. It's an interesting twist on the biblical Adam and Eve tale, where God made shame and sin an eventual certainty.

The Bible relates that God placed the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in the Garden of Eden, where Adam and Eve could not resist Satan's temptation to eat its forbidden fruit. In an inversion of the biblical creation story, the Ho claim that temptation and original “sin” are not from Satan, but are gifts from God. And the original sin, as they tell it, led not to being cast out of the garden and condemned to hard labor, but to a golden age of universal peace, harmony, and fecundity on Earth.

Here is the Ho creation myth, “The Story of Past Times,” as K. C. told it:

Once there was old man Luku and old woman Lukumi.

They two were alone on Earth.

There were forests and mountains everywhere.

There were beautiful springs, with fruits, flowers, leaves, trees and stones.

Old man Luku and old woman Lukumi were very happy eating fruits in the trees.

They two had no sinful thoughts in their minds.

As for clothes, they didn't have any on their bodies.

God thought, “If they stay like this, there will be no more generations.”

So God came down, and taught them how to make liquor from grass seeds.

They drank liquor in a cup made from leaves of the sar-fruit tree, and got drunk.

Then their minds felt another type of joyful thoughts;

About coming together as man and woman.

They started copulating, and felt shame and arousal.

So they covered each other up at the waist with tree bark.

Ten months later from Lukumi's body, a boy child was born.

In this manner, they bore seven boys and seven girls.

Thus they spread us humans on this Earth.

It was a Golden Age at that time.

There was no cheating, quarreling, cruelty, nothing bad.

There was no cold or starvation, fever or sadness.

The people remained in joy, happiness and peace.

This is called paradise.

8

As K. C. narrated the story, a local group of Ho schoolchildren clustered around. Most of them could not read and write their Ho tongue, and they seldom heard it spoken at their boarding school. Raised to be modern citizens of India, speaking English and Hindi, they nonetheless listened eagerly to the ancient tongue. They felt proud of their Ho heritage, pleased to know that it could offer a tale racier than any Bollywood flick.

What is the value of such antiquated myths in the modern world? Every creation story is an attempt to make sense of the universe and mankind's place in it. We may be indifferent to the passing of the drunken Ho creation myth. But if it fades, we lose as rich a world of possibilities as we ever could have inhabited, or even imagined.

K. C. Naik Biruli, a Ho orator, demonstrates the use of the Warang Chiti writing system, 2005.

A final twist in the story of Ho is the fractious debate over how it should be written. Alphabets are among the most politicized of human creations, and many small language communities find themselves locked into standoffs about how to write the sounds down on paper. For the Ho, their writing system, called Warang Chiti, invented by the revered pandit Lakho Bodra, has a mystical dimension. The first letter is the sacred symbol Om, chanted in meditation. It has no use whatsoever in the writing system, but bestows on the alphabet a sacred character. What follows Om is a collection of the most motley and odd-shaped symbols imaginable, including one that resembles a bolt of lightning and another that could be male genitalia. Those among the Ho who espouse this unique alphabet are fiercely proud of it. For them, each letter has its own mythology, signifying by its shape and sound the wailing of a newborn child, for example, and that same child when a bit older toddling and falling, or bodily functions such as vomiting. Others signify the sound of a tree falling, the shape of a plow, or a leaf cup from which to drink home-brewed liquor, as in the Ho creation myth. Each letter symbol tells a story, and together they relate an entire worldview. Some Ho thus consider writing sacred and believe that anyone using the letters should abstain from certain foods such as tamarind.

The world's oddest alphabet may turn out to be a barrier preventing Ho from entering the digital age. Or, with proper positioning, it could continue to provide a unique look and source of pride. Working with Greg Anderson and script specialist Michael Everson, we've petitioned the Unicode Consortium, the body that decides which scripts can be written on computers worldwide, to include Ho symbols. I imagine a day when the odd Ho letters will be as commonplace as Japanese

kanji

and will carry the most sacred and trivial of messages across the Internet.

A STORY MAP OF THE WORLD

As languages fall into forgetfulness, stories, songs, and epics approach extinction. We stand to lose entire worldviews, religious beliefs, creation myths, technologies for how to cultivate plants, histories of human migration, and collective wisdom. But it is not too late to record and sustain these rich traditions.

Imagine a story map of the world, one that identifies the hotspots where stories survive as a vital and wholly oral art form. Such a map would be a kind of inverse pattern to a world literacy map. In the places where literacy is most entrenched, memory has atrophied and almost no one memorizes or retells oral tales anymore. Yet at the fringes of the literate realm, deep pools of living memory remain. In the world's remaining oral cultures, unwritten stories still thrive. They change and evolve in an unbroken chain of narrative and memory.

Such story hotspots are as special as they are increasingly rare. Efforts to listen to and record small languages and their story traditions deserve our urgent attention. This must be accomplished while the elderly storytellers are still talking. If tales fall into disuse without being documented, we won't even know what we are losing.

Orality, the virtuosity of verbal art, is deeply disrespected and neglected in modern society. Any report on Third World development will trumpet high rates of illiteracy as a key indicator of stunted progress and will challenge policymakers to stamp out illiteracy. Policy and literature on human development routinely fail to recognize high percentages of orality, however, or to celebrate the verbal arts as an indicator of an intellectually and artistically accomplished society.

Acquiring literacy does open new doors for development, but what is the trade-off if ancient oral cultures are jettisoned, entire histories and moral codes wiped from memory? Why can't the two systems coexist? If we can overcome our bias toward literacy and appreciate the creativity and beauty of purely oral cultures, we will open a door to entire new vistas of the world and humankind's place in it. That door, still ajar in 2010, may soon close forever. Elderly storytellers around the world are eager to share their tales, generous with their wisdom, playful with their metaphors. Let's take the time to hear the stories, and be enriched.

BREAKING OUT IN SONG

It has become evident that practicing one's cultural heritage and speaking one's heritage language promotes self-esteem in young people.

âHarold Napoleon

SONGS MAY BE

nearly endangered as stories, and though people will never cease singing, local musical traditions often struggle to survive. Global culture cuts two ways: it may stifle local creativity by bringing hugely admired genres that outpace older ones in popularity, but it may also provide the seed for new creativity and give little-heard singing styles a new, global audience. Ethnomusicologists around the world are racing the clock, just as linguists are, to record and help revitalize the numerous ways of singing that may still be found. Many of the endangered language communities I describe in this book have song styles that are utterly unique and equally endangered. Sometimes songs can outlast the languages that spawned them; they may be all that remains of an ancient culture.

Once my dissertation was defended and I earned my Ph.D., I could hardly wait to begin traveling again. I was lucky enough to get a generous research grant from the Volkswagen foundation, based in Germany. Those funds gave me carte blanche to organize as many expeditions as I wished over five years to explore southern Siberia and Mongolia's smallest, most hidden tongues. Flush with grant money and a sense of discovery, I hastily assembled my dream team in the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk.

1

Together in the dead of winter, we set off on what would be the craziest, scariest expedition I have ever had. Our destination, Tofalaria, one of the most remote, inaccessible, and godforsaken places on Earth. What I would witness there would change me forever.

The Trans-Siberian Railway wends for more than 5,700 miles across one of the most boring landscapes imaginable. If you spend three, four, or even six days riding the train, which slugs along gently at a speed of about 40 miles an hour, you can literally see nothing but birch trees and grass all day long. Most of Siberia is a vast water world, a swampy delta, the mushy ground interspersed between some of Earth's largest rivers, the Yenisei, the Ob, and others. Underneath, not so very far down, lies permafrost, which is now melting and will fill our atmosphere with more methane than any other polluting source on the planet. So potent is the methane from melting permafrost that in midwinter you can take an ax, walk out onto a lake that has a foot-thick cover of ice, chop a slit in ice, and light a match over it. You'll produce an enormous whoosh of flame that shoots out of the ice as the methane burns.

2

Siberia is both literally and figuratively Earth's coldest hotspot.

I landed in Krasnoyarsk, where I met the rest of my teamâwhich included Greg Anderson, one of the leading experts on Siberian languages, and Sven Grawunder, an expert on phonetics and making recordings of obscure languages, along with a native Siberian guide and a driver. March was not the ideal time to trek into the backwoods of Siberia, and we waited three shivering days at the local hotel in Nizhneudinsk until the weather cleared. We whiled away the time playing cards, buying supplies, and drinking tea. While waiting at the airport, we noticed that our recording equipment was beginning to malfunction in the cold, so we cut up our thermal socks to sew little coats for our video cameras.

We finally made the bone-chilling, one-hour flight in a decrepit Soviet-era plane and landed on a meadow in Alygdzher, the largest of the three Tofa villages. No one was expecting us, of course, so we hitched a ride on a cart into town and ended up at the local clinic, which had a small guesthouse out back. We shared the space with a young Russian couple who had come to evangelize the natives. They were kind and generous and even put on a little celebration for my birthday.

News of our presence in the village spread so fast that we did not even have to seek out speakers. People began to point out to us who were the elders, and where they lived. Not all of them would speak to us, though. One fled from his house as we approached, one shut the door in our faces, and another was so painfully shy that she simply stared down at the floor.

At last, two elderly sisters, Galina and Varvara Adamova, welcomed us into their tiny log house, bare except for two beds and a small wooden chest containing some crusts of bread. I had seen Siberian poverty before, but this was true deprivation. There was no warmth or food, no blankets or pillows, nothing but two beds with dirty mattresses and a single wooden bench in the kitchen. Next to the stove, on the floor, lay a Russian New Testament, a gift from the missionaries. Varvara had put it to good use, carefully tearing out pages one by one to roll homemade cigarettes with

mahorka,

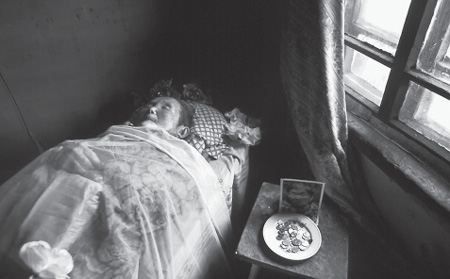

the cheap tobacco that elderly ladies in Russia like to smoke. Galina, the younger of the two, could barely stand upright, and leaned on a walking stick. Neighbors told us that in the 1950s she spent five years in a Stalinist labor camp for some minor infractionâno one could remember what. Somehow she survived that horror, and though she returned home with ruined health, she became a promoter of Tofa cultural identity. She and her sister were photographed in the 1980s sitting on the backs of reindeer dressed in traditional costumes they had sewn themselves. That photo became iconic, reprinted in books and calendars about native Siberians.

Galina Adamova, a last speaker of Tofa, on her funeral bier, Russia, 2001.

Galina and Varvara loved to sing. They broke into song at any opportunity. The problem was, there only seemed to be one song, or rather just one melody for every Tofa song. Our team musicologist, Sven Grawunder, had traveled all over Siberia and many other places documenting special vocal techniques and ancient song traditions, but even he was stymied by this impossibly small repertoire. Each time we asked for a different song, we were treated to what sounded to us like exactly the same song with different words. It was really a single couplet, with only five distinct notes. We would later record four other singers who all seemed to be doing the same thing, even though singers in the other village insisted they were singing a different song. It again sounded exactly the same, the simplest possible pattern of five notes, repeated in two lines. It was as if every single song the culture possessed was as minimal as the first two lines of “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star,” with no further variation possible.

Another odd thing they did with the songs was to cleverly disguise the words, interrupting every syllable with a kind of yodel, so that even other Tofa speakers could not repeat or understand most of the words. So, a sentence like “I'm riding my reindeer” would come out as I-

oho

-m ri-

oho

-ding my-

oho

rei-

ehe

-ndeer. It was like a speech-disguise game, pig latin or

ubbi dubbi,

scrambling syllables to keep the meaning secret.

Our initial hypothesis was that in past times the Tofa must have had a rich song tradition, as did all the native people around them, but that due to cultural decline they had forgotten all their songs apart from one basic melody. But after hearing dozens of variations on the theme and finding half a dozen people in two villages who eagerly performed songs for us, we realized this was not the tail end of some tradition. Rather, it was a truly ancient, basic, primordial song tradition that had persisted, resisting outside influences, special and insular unto itself. It was the original song for the Tofa people, perhaps the only one they had ever sung or cared to sing, even though they had been exposed to many other types of songs and melodies over the centuries of contact with outsiders. Nor was their musical ability limited. Like other Siberians, they had a heightened attunement to forest sounds and animal calls and, using their mouths, birch-bark horns, or birch-bark whistles, could imitate many different kinds of animal sounds. And their language boasted a large number of words describing different types of sounds.

We were excited to be sitting in the presence of two distinguished elders, but getting anything useful out of them proved difficult. Drunken relatives and neighbors frequently barged into the house and wanted to “help” us, rambling incoherently. The sisters, though eager to talk, were missing teeth and spoke nearly incoherently, whether in Tofa or Russian. And after recording several songs and deciding there was really just one song, we figured we'd gotten what we could. We sighed at the fact that, of the elders we'd met so far, several were too shy or too incapacitated to talk, while the sisters clearly wanted to talk but were incomprehensible. If this was all that remained of Tofa, we were in trouble.

One of the most animated moments we captured was when we managed to ask in the Tofa language about shamans. We knew from historical accounts that the Tofa were animists, believing in a profusion of local spirits, and that they had practicing shamans as recently as the 1950s. We had even seen a shaman's costume in the local museum in Nizhneudinsk. We figured the sisters would have witnessed shamanic rituals themselves. Though it had been a forbidden topic for many years under communism, we hoped they might be willing to talk about it.

No sooner did I utter the word “shaman” than Galina spryly jumped up from where she had been sitting on her bed. She began a little dance around the room. She waved her stick in the airâit suddenly was no longer a walking stick, but a shaman's staff, a

dayak

. She pretended to hold an invisible drum in one hand and beat it with her staff. “Dang, dang, dang,” she sang, making drumlike sounds. “The shamans danced like this,” she said. “If it's a good shaman, you will get well,” she added, attesting to the healing powers once exercised by shamans.

I sucked in my breath and looked over at Sven, who was steadily aiming our camera at Galina. We had captured a truly special moment on film. This was a woman whose very culture had nearly been driven out of existence and who had personally been exiled to a labor camp. Any kind of cultural pride had been downright dangerous in her lifetime. Yet here she was, singing and dancing and celebrating the shamanic past, putting it on display for visiting foreigners.

As we left, she hugged us and said, “Come back soon!” Little did we suspect how soon we would be saying goodbye to Galina, and even though most of what she said was cryptic, we faithfully recorded every word. A few months later, on a return visit, we followed Galina's funeral procession and paid our respects as the village bid yet another elder farewell. The day after Galina was buried, her elder sister Varvara knocked on our door. “I've come to sing for you,” she declared, breaking into the familiar five-note melody.

SINGING THE FLOCK BACK HOME

I crouched in the snow and waited quietly, deep in the woods on a northern slope of the Altai Mountains in Mongolia. My friend Mergen of the Tsengel people, an expert guide and hunter, sat next to me, waiting with his rifle and binoculars. He seemed to be hearing and seeing things I could not. His senses had been sharpened by thousands of hours spent observing this forest ecosystem, attending to bird calls, insect chirps, and details as minute as which side of a tree moss grows on and how deep an imprint a deer hoof makes in the moss underfoot. Mergen, at the relatively young age of 30, was already renowned for his hunting prowess: he bagged marmots in the fall, elk in the spring, wolves and foxes in winter, and squirrels in the summer. He knew the behavior patterns of each animal, its characteristic habits, resting places, and sounds. Stripping away a patch of birch bark about the width of two fingers, Mergen could make a birch-bark hunting whistle, called an

etiski,

in just minutes. Its squealing call resembled that of a small wild pig and could lure bears to come out in search of a meal. With more birch bark, carefully peeled away and soaked in a stream to make it pliable, he could make a

murgu,

an elk hunting horn that simulated a mating call.

Mergen's language, a minor dialect of Tuvan with only about 1,200 speakers, has a remarkably rich system of sound mimesis, words that mimic natural sounds. His people, in part because of the landscape where they live and the hunting and herding activities they engage in, have both a heightened sensitivity to the soundscape and an enhanced ability to mimic and stylize sounds. The language has many more words than does, for example, English to describe different types and qualities of sounds. It also has a “productive” system, which means that speakers can make up

new

sound-symbolic words on the fly, and other speakers can understand them.

The system uses high vowels (pronounced with the tongue high in the mouth, such a

ee, oo

) to describe high-pitched sounds, such as a tin can clattering down a cliff. And it uses low vowels

aa

and

oh

to describe low-pitched sounds, such as a large wooden barrel rolling over rocks. It also uses consonants to express particular types of sounds, so that fricatives (sounds like

s, sh, f,

and

z

) express friction sounds (such as scraping the soles of your feet across shards of broken glass) and plosives (sounds that involve a burst of released air, such as

p, b, t,

and

k

) describe impact sounds, such as a boot being thrown against a wall. By combining these innovative uses of vowels and consonants, a speaker can imagine and make up an entirely new word to describe, say, the squeaking sound made by new leather boots (such a word would contain high vowels and fricative consonants). Or the sound made by dropping a boulder into a lake, which would use low vowels and plosives. Or a bear scratching its back against tree bark.