The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (52 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

3

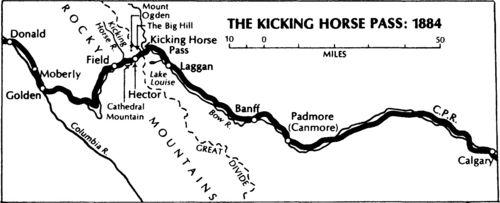

The Big Hill

In the Rockies, that summer of 1884, the weather was wet and miserable. The naked peaks were masked by dismal clouds and the numbing rain that poured down ceaselessly turned the milky Kicking Horse into a torrent that spread itself across the Columbia flats, cutting the tote road so badly that it was almost – but not quite – impossible for the teams to struggle through. Severe frosts persisted until late June. Snow swept the upper slopes of the mountains. In the shacks that did duty as offices near the summit, roaring fires had to be maintained well into the early summer.

The rails had sped out of Calgary the previous fall along the easy incline of the Bow Valley at the same rapid rate that had taken them across the plains. Indeed, another record had been set. The

CPR

gangs set out to better the achievement of the Northern Pacific, one of whose track-laying teams had captured the short-distance record by laying six hundred feet of track in six and a half minutes. Not far from Bow Gap, where the roadbed headed for the Kicking Horse Pass, the Canadians managed to lay six hundred feet in four minutes and forty-five seconds. It was a considerable feat, since the Northern Pacific had achieved its result by sponsoring a race between two gangs working against each other. On the Canadian line, as one onlooker noted, “it was accomplished in cold blood and without the least preparation except putting more than the ordinary quantity of rails on the car.”

Once the pass was entered and the incline grew steeper, the speed of track-laying slowed down. The rails crept to within a few miles of the summit and came to a halt. The track crews were laid off and thousands of men quit the mountains, leaving behind a skeleton force of five hundred whose job was to cut timber for the coming season. They produced half a million railroad ties and twenty thousand cords of fuel for the locomotives, coal being far too expensive to haul to such heights.

For all of the summer of 1884, the construction headquarters of the Mountain Division of the

CPR

remained near the summit where the end of track stood the previous fall. The community that sprang up was at first known as Holt City, after Tim Holt, a veteran of the Zulu wars who ran the company store, and whose brother, Herbert, was one of the major contractors on the division. Later on it acquired the name of Laggan; today it is known as Lake Louise station.

Holt City, surrounded by acres of lodgepole pine, sat on the banks of the Bow – the beautiful Bow, “swift and blue, and heavenly and crystal, born of the mountains and fresh from snowfield and glacier.” It was to

this little camp, raucous with the pandemonium of squeaking fiddles, that the pay car came on its monthly rounds; and it was here that men crowded in on payday to squander their earnings at the three hotels, or at the poker, faro, and three-card monte tables, or at the surreptitious little cabins along the route that did duty as blind pigs.

James Ross had announced that he would need twelve thousand men in the mountains in the summer of 1884. By June they were pouring in. Every train brought several carloads of navvies who had come across the plains from Winnipeg. Turner Bone, who worked for Herbert Holt that summer, recalled that the scene “might well have been compared to a gathering of the clans in response to the call of the fiery cross; all keyed up and ready to go.” They tumbled off the cars and trudged up the right of way to the construction camps, in a land hitherto seen by only a handful of men, singing the song of the construction men in the mountains:

For some of us are bums, for whom work has no charms

,

And some of us are farmers, α-working for our farms

,

But all are jolly fellows, who come from near and far

,

o work up in the Rockies on the

C.P.R.

One of them, a young labourer named George Van Buskirk, wrote to his mother in the East, shortly after his arrival on June 17, that “the scenery out here for wildness & grandeur is well worth what I have gone through.” It was a considerable tribute to the future tourist attractions of the mountains, for Van Buskirk had gone through a good many trials in the previous weeks. He had arrived in Calgary absolutely penniless, “in a foreign land, 4,000 miles away from home and no money and not a chance to get any.” By pawning his baggage and selling his bridle and saddle he finally managed to reach Holt City with four dollars in his pocket. It was not hard to find work. “A rough looking labour man” instantly offered him a job; he was about to accept when a second man appeared and said he

wanted some men to shovel. Van Buskirk liked his looks better and accepted. He was told to throw his baggage onto a cart and follow behind it. He hiked ten miles “over the hardest road it was ever my luck to see – nothing but rocks and mud up to my knees” and, about one o’clock that afternoon, “pretty well fagged out,” was put to work erecting tents and chopping down foot-thick trees for shanties. In spite of the scenery, young Van Buskirk was pretty discouraged by evening: “Taking it all and all the North West is not what it is cracked up to be,” he informed his mother. “Some of these chaps who write in the papers ought to be shot, for the country although a fine one is terribly overrated & the reports one sees mislead entirely.” A fortnight later he had cheered up considerably: “I am very well with the exception that my blood is very coarse from eating strong food. Too much beans.”

The British novelist Morley Roberts, who arrived that summer, watched the tenderfeet from the cities heading off up the line to the various camps – a miscellaneous throng of about a hundred, loaded down with blankets and valises – and noted that many had never worked in the open air at all. Some indeed had not done a hard day’s work in their lives:

“It was quite pitiful to see some little fellow, hardly more than a boy, who had hitherto had his lines cast in pleasant places, bearing the burden of two valises or portmanteaus, doubtless filled with good store of clothes made by his mother and sisters, while the sweat rolled off him as he tramped along bent nearly double. Perhaps next to him there would be some huge, raw-boned labourer whose belongings were tied up in a red handkerchief and suspended from a stick.”

Behind the labourers came the first tourists, some of them travelling all the way from Winnipeg to gaze upon the wonders of the mountain scenery, which the construction of the railway had suddenly disclosed. “Every week now sees excursions, walks, horseback rides, picnics, mountains scaled, scenery explored, and a dance or two.” The government’s engineer-in-chief, Collingwood Schreiber, was ecstatic, as all were, about the scenery: it “far surpasses the scenery upon the other transcontinental lines, if I mistake not it will be a great resort for tourists and madmen who like climbing mountains at the risk of breaking their necks.”

Some of that scenery was fast disappearing under the human onslaught. “Round me,” wrote Morley Roberts, “I saw the primæval forest torn down, cut and hewed and hacked, pine and cedar and hemlock. Here and there lay piles of ties, and near them, closely stacked, thousands of rails. The brute power of man’s organised civilisation had fought with Nature and had for the time vanquished her. Here lay the trophies of the battle.”

The mountainsides that year were ablaze with forest fires started by the construction workers. At times the entire pass, from the summit to the Columbia and westward, seemed to be aflame. “The mountainsides bear testimony to the destructive tendencies of irregenerate

[sic]

man,” the Grand Trunk’s Sir Henry Tyler wrote to his wife from End of Track the following year. Tyler, making a careful inspection of the rival line, was horrified to learn that some of the fires had been purposely ignited in his honour. “Several railway men had argued that it would be right to celebrate our visit by means of a presidential blaze!”

The most distinguished tourists that summer were the members of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, who held their annual meeting in Canada in 1884. The association, including the future Lord Kelvin, then plain William Thompson, went to End of Track and beyond, where they almost lost Alfred Selwyn, the distinguished geologist. Selwyn was crossing a temporary wooden scaffold over a ravine when an avalanche thundered down, tearing the bridge apart. The geologist was carried a considerable distance, caught in a mass of broken and dislocated timbers, but emerged unhurt.

Avalanches were frequent in the Rockies that season, many of them set in motion by the continual blasting that went on along the line. Everyone who witnessed a Rocky Mountain avalanche was awestruck. “They resembled exactly a large mow taken down with a scythe in the fields,” Alexander Mackenzie wrote to his daughter. (The former Liberal Prime Minister was on a tour of the North West as a guest of the railway and, as a result, was to change his mind about the barrenness of prairie land.) “If one of these avalanches should descend on the road, no protection man could find would prevent a complete wreck of road, bridge or train.” Sam Steele wrote that “glaciers, which had never left their rocky beds … broke away and came crashing down, cutting pathways from a quarter to half a mile wide through the forest below.” Steele saw one avalanche descend five thousand feet from a summit with such velocity that it tore directly across a valley and up the opposite side for eight hundred feet.

Under such conditions, the work went on at a killing pace from dawn to dusk. On one contract the workmen averaged more than ten hours of labour a day every day for a month. Some of them had thirteen or fourteen hours a day to their credit. If rain made work impossible, they caught up in sunny weather. Sometimes they even worked by moonlight.

As always, a good portion of many men’s wages was spent on illegal liquor. Gamblers, whiskey peddlers, and criminals of all sorts were filtering into the mountains from the Northern Pacific’s territory south of the border

and establishing their dens on every creek and gully along the right of way.

In British Columbia the Mounted Police jurisdiction was limited to the twenty-mile belt along the surveyed line of the railway, within whose confines it was forbidden to sell (but not to possess) liquor. This belt had been proclaimed by the federal government under an act for the preservation of peace on public works. Bartenders could be fined for the first and second offences and imprisoned for a third, but they were able to circumvent the intent of the law by transferring the goodwill of their establishment to someone else and thus continue in business. The temperance belt was so narrow that it was possible for thirsty navvies to walk ten miles to the provincial jurisdiction and spend all their wages on a single spree. The obstacle here was the government of British Columbia, which did not want to be deprived of the tax money the liquor sales provided. Its practice was to give anybody a licence who asked for one within the belt and outside of it. A frustrated Sam Steele, watching construction grinding to a halt as the result of drunkenness, urged Ottawa to increase the width of the railway belt to forty miles and to allow magistrates to imprison whiskey peddlers on the second offence. The federal government complied and construction resumed its normal pace. The wholesale and retail stores had to move back twenty miles from the railway and, as Steele remarked, the navvies found a twenty-mile walk too long for the sake of a spree.

The railway workers lived in every kind of accommodation along the line – in tents of all shapes and sizes, in box cars rolled onto sidings, in log huts and in mud huts, in shanties fashioned out of rough planks, and in vast marquees with hand-hewn log floors, log walls, and a box stove in the centre. Over the whole hung the familiar pungency of the bunk-house, an incense almost indescribable but compounded of unwashed bodies, strong tobacco, steaming wool, cedar logs, and mattress straw. Such communities had an aura of semi-permanence, unlike the portable towns of the prairies; the track did not move mile by mile or even yard by yard. On some days it seemed to creep along inch by inch as the contractors attacked the granite bulwarks with tons of dynamite and hordes of workmen.

The work was often as dangerous as it was back-breaking. Near one of several tunnels along the Kicking Horse the cut in the hill was so deep that the men worked in three tiers. At the very top, the route was being cut through gravel; in the centre the gravel gave way to blue clay; below the clay was hard rock. The men on the lowest tier, working just above the layer of rock (which would have to be dynamited), attacked the clay

from beneath. Twenty to thirty feet above them a second gang worked, chopping out the gravel and wheeling it away in barrows. The high gang removed the top layer of sand and stumps. Those at the very top worked in comparative safety; the middle gang was in some peril because they had to watch out for rocks that might topple down on them; but the lowest gang was in constant danger – from both benches above them came a continual shower of rocks. Morley Roberts, who worked on the lowest tier, reported that he never felt safe for a single moment. Every sixty seconds or so, all day long, somebody above would cry: “Look out below!” or “Stand from under!” and a heavy stone or boulder would come thundering down the slope, scattering the men on both sides. On his third day on the job a foot-thick rock weighing about eighty pounds struck him above the knee and put him out of action for five days. It was a welcome respite; the literate vagabond whiled away his convalescence with a copy of Thomas Carlyle’s

Sartor Resartus

.