The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (60 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

The concept of a transcontinental railway was also responsible for changing the casual attitude towards time. Heretofore every city and village had operated on its own time system. When it was noon in Toronto, it was 11.58 in Hamilton, 12.08 in Belleville, 12.12& in Kingston, 12.1632 in Brockville, and 12.25 in Montreal. In the state of Michigan alone there were twenty-seven different times, most of them established by local jewellers. In some cities (Pittsburgh was one) there were as many as six versions of the correct time, varying by as much as twenty minutes.

As the railways lengthened across the continent, the constant changing of watches became more and more inconvenient. Worse, railway passenger and freight schedules were in a state of total confusion. Every railroad had its own version of the correct time, based on the time standard

of its home city. There were, in the United States, one hundred different time standards used by the various railroads. In order that passengers could compare the various times, large stations were forced to install several clocks.

On New Year’s Day, 1885, the Universal Time System was adopted at Greenwich. About a year earlier the major American railways and the Canadian Pacific had brought order out of chaos as far as their own schedules were concerned by adopting “railway time.” The Thunder Bay

Sentinel

welcomed the change in an editorial and urged that it be taken up by the community:

“Everyone in Port Arthur, except perhaps railway men, keeps a different time. Scarcely half a dozen watches will be found to correspond. If a person wishes to catch a train he will at one time be half an hour ahead and again be that much behind.… It is the same with men working at offices or at the bench or in whatever sphere their duty calls them. Every church apparently has its own time, the only bell ringing with any degree of regularity being that of the Catholic church. Now all this difficulty could be done away with by having one time in town and everyone keeping their watches and clocks together.…”

The local jeweller, W. P. Cook, announced that he would adopt the

CPR’S

time, putting his regulator back about twenty-two minutes, and that he would send the new time to all the clergymen in Port Arthur so that the bells might ring in unison. The change was a fundamental one, for it affected in a subtle fashion people’s attitudes and behaviour. Such concepts as promptness and tardiness took on a new meaning. Schedules became more important when they became more precise. The country began to live by the clock in a way it had not previously been able to do.

Much of the credit for this went to Sandford Fleming, the man who had originally planned the transcontinental railway in Canada. More than twenty years before, when Fleming was first contemplating the idea of the Canadian Pacific, he had realized that the plan would immediately raise difficulties in the computation of time. His views were confirmed as the railway project took shape. In 1876 he prepared a memorandum on the subject, which was widely circulated. Two years later he made energetic efforts to read a paper on the concept before the British Association for the Advancement of Science but was rebuffed as an unknown and a colonial. It was, Fleming later wrote, “one of those acts of officiai insolence or indifference so mischievious in their influence and so offensive in their character, which I fear, in years gone by, too many from the Outer Empire experienced.” Nonetheless, Fleming persevered in his study of time

and the Canadian Institute, which he had founded, recognized him in 1885 as “unquestionably the initiator and principal agent in the movement for the reform in Time-Reckoning and in the establishment of the Universal Day.”

The adoption of the new time system in that first month of 1885 was a relatively minor event as far as newspaper readers were concerned. The world was in a ferment and, for the first time, the new nation had a personal stake in the outcome. Up the steamy cataracts of the Nile a flotilla of boats manned by Canadian voyageurs was slowly making its way on a vain mission to relieve Khartoum and rescue that flawed hero, General Charles Gordon, from the clutches of the Mahdi. This was the nation’s first expeditionary force and it had its origin in the same series of events that helped to launch the idea of a Pacific railway. Its commander was General Garnet Wolseley, who had taken Canadian and British troops across the portages of the Shield to relieve Fort Garry during the Riel uprising of 1869–70. It was Wolseley’s idea to use some of the same French Canadians to man the Nile brigade. The commander of the flotilla was William Francis Butler, another officer familiar to Canadians, for it was he who had first excited the nation with his descriptions of the Great Lone Land. The railway had put that phrase, along with the old portage route, into the discard. Never again would a military force require seventy-six days to make its way to the North West.

Because of the railway, the settled and stable community of Canada was entering a new period of instability. The closed frontier society of 1850–85 was being replaced by the open frontier society of 1885–1914. After 1885, the Canadian Shield ceased to be a barrier to westward development. The railway would be a catalyst in new movements of population (such as the Klondike gold-rush) and in a variety of social phenomena that would destroy the established social order – agrarian agitation, new political parties, odd religious sects and communities, and the continuation of that ethnic diversity known as “the Canadian mosaic.”

Eighteen eighty-five was as dramatic a year as it was significant. As the nation became vertebrate, events seemed to accelerate on a collision course. In Montreal, George Stephen, teetering on the cliff edge of nervous collapse, was trying to stave off personal and corporate ruin. In Ottawa, John A. Macdonald faced a cabinet revolt over the railway’s newest financial proposals. In Toronto, Thomas Shaughnessy was juggling bills, cheques, notes of credit, promises, and threats like an accomplished sideshow artist in order to give Van Horne the cash he needed to complete the line. On Lake Superior, Van Horne was desperately trying to link up

the gaps between the isolated stretches of steel – they totalled 254 miles – so that the

CPR

might begin its operation as a through road. In Manitoba, the political agitation against both the government and the railway was increasing, in spite of Macdonald’s promise that the hated monopoly clause would be dropped from the contract once the job was finished. In St. Laurent on the Saskatchewan, Louis Riel, the leader of the Red River uprising of 1869, was back from his long exile and rousing the Métis again. On the far plains and in the foothills, the Cree chieftains Big Bear and Poundmaker were agitating for new concessions from an unheeding government. And in the mountains, the railway builders faced their last great barrier – the snow-shrouded Selkirks.

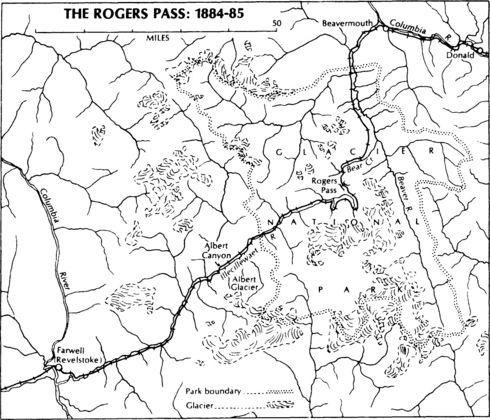

The Selkirks remained a mystery almost to the moment when the steel was driven through. There was something uncanny about those massive pyramidal peaks, scoured by erosion and rent by avalanche. As late as 1884, when the rails reached the mouth of the Beaver, powerful voices had been raised urging that the road circumvent the mountains by following the hairpin valley of the Columbia. Even in 1885, after the right of way was cleared and the steel had started to push up the valley of the Beaver towards the Rogers Pass, a pamphlet was printed and distributed in Montreal called

An Appeal to Public Opinion against a Railway Being Carried across the Selkirk Range

. The uneasiness was felt in the highest echelons of the company, and with good reason: for the very first time the locomotives, rather than the Indians, were blazing a pioneer trail.

Van Horne had thought long and hard about using the Rogers Pass in preference to the longer but easier Columbia Valley. Publicly he called it “one of the finest mountain passes ever seen,” but privately he had reservations. On the one hand there would be heavy gradients – probably greater than two per cent – for some forty miles. That would mean heavy assisting engines and costly wear and tear on the track. Against that there was the saving of the cost of operating nearly seventy-seven miles of additional line, which meant a reduction of two hours in passenger time and four hours for freight trains. This latter consideration was of great importance when competing for through traffic and, in the general manager’s opinion, “would alone be sufficient to justify the use of heavier gradients.” Van Horne, who disdained circumlocution, opted for the Rogers Pass.

There were problems in the Selkirks, however, on which no one had reckoned, and these began to manifest themselves in the first months of 1885. By that time the right of way had been cleared directly across the mountains, from the mouth of the Beaver River at its junction with the Columbia on the east to the mouth of the Illecillewaet at its confluence with the Columbia on the west. More than a thousand men, strung out in scattered construction camps and individual shacks along the tote road, were toiling away in the teeth of shrieking winds that drove snow particles like needles into their faces. Seen from the top of the pass, the location line resembled a wriggling serpent, coiling around the hanging valleys, squeezing through the narrow ravines, and sometimes vanishing into the dark maw of a half-completed tunnel. High above, millions of tons of ice hung poised on the lip of the mountains, the birthplace of the avalanches and snowslides that constantly swept the area.

The snowslides occurred largely on the western slopes of the mountains. Like the lush vegetation – the gigantic cedars and huge ferns, which astonished every traveller who crossed the Rogers Pass – they were the result of an extraordinary precipitation. The moist winds, blowing across British Columbia from the Pacific, were blocked by the mountain rampart, which relieved them of their burden of water vapour. The rainfall each summer was heavy and the snowfall phenomenal. An average of thirty feet of snow fell each winter at the Illecillewaet Glacier; at the summit the average fall was fifty feet.

This natural phenomenon posed a threat to the entire operation of the railway. In midwinter, the Rogers Pass was almost impossible to breach. On February 8, 1885, a North West Mounted Police constable named Macdonald set out from Second Crossing on the Columbia, at the site of the future city of Revelstoke, and rode thirty miles up the western slopes of the Selkirks towards the pass. When he was within fifteen miles of the summit he could no longer ride and was able to proceed on foot only with difficulty. The pass, he reported, was one mass of avalanches, slides and fallen glaciers. The snowslides were solid packs of ice and were sometimes fifty feet in thickness. Through this frozen jungle the railroad builders intended to force the line.

The day Macdonald commenced his journey, a slide six miles west of the summit buried the camp of William Mackenzie, killing the cook. On the same day a second slide, four miles west of the summit, buried three men alive. A third slide, closer to the summit, destroyed a company store. There were several men in the building at the time but fortunately the skirt of the avalanche swept by and only the western portion of the store was buried; the occupants were able to squeeze out through a window. It took Constable Macdonald a day and a half to cover the final fifteen miles to the summit. From there to Beaver River, thirty miles away on the drier eastern slopes of the mountains, it was a comparatively easy ride.

The slides on the western slopes formed the chief topic of conversation among construction workers that winter. “The workmen on the road seem panic-stricken,” one reporter remarked. “And many of them are refusing to work on account of the danger, others are striking for higher wages, the demand being for $3.50 per day.” The situation grew worse. Herbert Holt lost sixty-five thousand dollars worth of supplies, all swept away by a vast slide at the end of February. By that time all communication between the summit and Second Crossing was cut off; supplies could no longer come in from Kamloops but had to be hauled up from Beaver-mouth.

A Selkirk snowslide was a terrifying spectacle. A quarter of a million cubic yards of snow could be detached from a mountain peak and come tearing down the slopes for thousands of feet, ripping out great cedars, seizing huge boulders in its grip, and causing an accompanying cyclone more fearful than the avalanche itself. This cyclone extended for a hundred yards or more outside the course of the slide and was known as the flurry, a term that scarcely did credit to its intensity. A few seconds before the body of the avalanche struck, the pressure of this gale force wind snapped off huge trees several feet in diameter fifty feet above the base

without uprooting them. The accompanying cloud of fine snow particles was impacted like moss against the windward side of the trunks. One such flurry was known to have picked up a man and whirled and twisted him spirally and so rapidly that when he dropped he was a limp mass without a bruise or a break in skin or clothing yet with every bone in his body either broken or dislocated. One snowslide, which stopped just short of the track near Glacier, was preceded by a flurry so powerful that it knocked eight loaded freight cars off the rails. The railway builders sometimes cut right through small mountains of debris left behind by such slides. One cut, about forty feet deep, was full of tangled trees and presented such a strange appearance when gulleted – the sawn stumps sticking out like raisins in a cake – that it was known as Plum Pudding Cut.