The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (28 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

The Indians could no longer carry packs weighing a hundred pounds. When the fish and game the Major had expected to garner along the way proved to be nonexistent, the party was forced to go on short rations. They were seldom dry. The heavy rains and wet underbrush, the continual wading in glacial waters and soft snow – some of the drifts were ten feet deep – the lack of proper bedding at chill altitudes (half a pair of blankets per man was all that Rogers allowed) – all these privations began to take their toll.

They held cautiously to the lee of an obelisk-shaped peak, which would later be named Mount Sir Donald, after Donald A. Smith. Here, in the cool shadows, there was still a crust on the snow which allowed them to walk without floundering. At four one afternoon they came upon a large level expanse that seemed to them to be the summit. They camped there, on the edge of timber, out of range of the terrible snowslides. When the sun’s rays vanished and the crust began to re-form they made a hurried trip across the snow-field. At the far end they heard the sound of gurgling water and to their satisfaction saw that it separated, some of it running westward, some to the east. They had reached the divide; was this the route the railway would take?

Mountains towered above them in every direction. A smear of timber extended half-way up one slope between the scars of two snowslides and they determined to make their ascent at this point. Each man cut himself a stick of dry fir and started the long climb. “Being gaunt as greyhounds, with lungs and muscles of the best, we soon reached the timber-line,” Albert Rogers recounted.

Here the going became very difficult. The party crept around ledges of volcanic rock, seeking a toehold here, a fingerhold there, staying in the shade as much as possible and kicking steps in the crust. Several feet above the timber line, the route followed a narrow ledge around a promontory exposed to the sun. Four of the Indians tied pack-straps to each other’s belts and then the leader crept over the mushy snow in an attempt to reach the ledge. He fell back with such force that he lost his footing and all four men plunged thirty feet straight down the dizzy incline, tangled in their pack-straps, tumbling one over another until they disappeared from sight. The others scrambled down after them; miraculously, none was injured.

It was late in the day when the twelve men reached the mountain top, but for Albert Rogers, at least, it was worth the ordeal:

“Such a view! Never to be forgotten. Our eyesight caromed from one bold peak to another for miles in all directions. The wind blew fiercely across the ridge and scuddy clouds were whirled in eddies behind great towering peaks of bare rocks. Everything was covered with a shroud of white, giving the whole landscape the appearance of snow-clad desolation. Far beneath us was the timber line and in the valleys below, the dense timber seemed but a narrow shadow which marked their course.”

The Major was less poetic, though he read a great deal of poetry and loved it. On occasions such as this it was his habit to doff his hat, ruffle his long hair, and say, reverently: “Hell’s bells, now ain’t that thar a pretty sight!”

The party had neither wood for a fire nor boughs for beds. They were all soaked with perspiration and were wolfing great handfuls of snow to quench the thirst brought on by their climb. “But the grandeur of the view, sublime beyond conception, crushed out all thoughts of our discomfort.”

They were in a precarious position, perched on a narrow ridge where a single false move could lead to their deaths. They crawled along the razorback on all fours until they encountered a little ledge in the shadow of a great rock, which protected them from the wind. Here they would have to wait until the crust formed again and the morning light allowed them to travel.

It was a long night. Wrapped in blankets, nibbling on dried meat and stamping their feet continually in the snow to keep their toes from freezing, they took turns flagellating each other with pack-straps to keep up the circulation. At two o’clock, the first glimmer of dawn appeared. They crept back to the ridge and worked their way down the great peak to the upper south fork of the river. It seemed to Rogers that this fork paralleled the valley on the opposite side of the dividing range through which, he concluded, the waters of the Beaver River emptied into the Columbia on the eastern flanks of the mountain barrier. If that was true, then a pass of sorts existed.

Unfortunately, he could not be sure. There were eighteen unexplored miles left, but by this time the party was almost out of food. Rogers’s notorious frugality had destroyed all chances of finding a pass in the season of 1881; he did not have supplies enough to allow him to press forward and so was forced to order his men to turn their backs on that tantalizing divide and head west again. He must have been bitterly disappointed. It would be at least another year before he would be able to say for certain whether a practical route for a railway led from the Beaver to the Illecillewaet. By that time the rails would be approaching the valley of the Bow, and he still had not explored the Kicking Horse Pass in the Rockies, which had scarcely been glimpsed since the day when James Hector, Palliser’s geologist, first saw it in 1858.

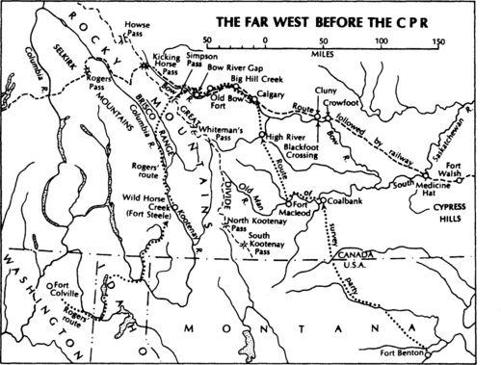

Rogers sent all but two of his Indians back to Kamloops. The others guided him down the Columbia and across the international border to Fort Colville in Washington Territory. There he hired a packtrain and saddle horses and made his way by a circuitous route back into the Koote-nay country to the mining camp at Wild Horse Creek.

The Major had a long trek ahead of him. He had that spring dispatched the main body of his survey party from the East to the State of Montana with directions to enter Canada from the south and proceed towards the eastern slopes of the Rockies by way of the Bow Valley. He planned to join them by crossing the Kootenay River, hiking over the Brisco Range, and then working his way down the Spray to the point where it joined the Bow. It was wild, untravelled country, barren of human habitation, unmarked by trails or guideposts; but short of going back to San Francisco and across the American West by train, it was the best route available to Rogers if he was to link up with his men on the far side of the mountains.

He did not take his nephew with him. It was late June by this time and it was imperative that somebody explore the Kicking Horse Pass from its western approach. Rogers decided that Albert must take the packtrain to the mouth of the Kicking Horse River and from that point make his way to the summit of the continental divide. Only one white man had ever come that way before – James Hector; but he had descended from the summit. Even the Indians shunned the Kicking Horse; they preferred to follow the Ottertail and go over the high pass (known as the Mac Arthur Pass) and then descend to the divide. The terrible valley of the Kicking Horse was considered too difficult for horses. On his first trip into the Rockies, young Albert, aged twenty-one – “that little cuss” as the Major fondly called him-was being asked to attempt a feat that no human being had yet accomplished.

2

On the Great Divide

Major Rogers and his men were advancing on the Rockies from three directions that spring of 1881. While Albert worked his way towards the unknown slopes of the Kicking Horse and his uncle guided his packhorses over the Brisco Range, the main body of surveyors, most of them Americans, were heading westward from St. Paul towards Fort Benton, Montana, the jumping-off point for the eastern slopes of the Canadian Rockies. Waiting impatiently for them at the steamboat landing was a 22-year-old stripling from Ontario. His name was Tom Wilson and he was positively lusting for adventure.

For many an eastern Canadian farmboy in the 1870’s, the lure of the North West was impossible to resist; it got into their blood and it remained in their blood all of their lives. They were raised on such romantic best sellers as William Butler’s

The Great Lone Land

and George Grant’s

Ocean to Ocean

. Soldiers back from the Red River expedition were full of tales of adventure in the wide open spaces. The North West Mounted Police, formed in 1873, were already forging an authentic Canadian legend in the shadow of the Rockies. To any lusty youngster, confined to the drab prison of farm and village life, the great lone land spelled freedom.

Tom Wilson was one of these. He was a rangy youth with a homely Irish face. His long jaw, high cheekbones, and prominent teeth gave him something of a horsy look, and this was perhaps prophetic for he would work with horses all his life. Later he would grow the shaggy moustache that was almost a trademark with Rocky Mountain packers. He was easygoing, industrious, good humoured, and incurably romantic. In 1875 at the age of sixteen, he quit school, bade good-bye to his family, and set off through Detroit and Chicago for the Canadian North West. At Sioux City he was overcome by a bout of homesickness and went back to Ontario.

Four years later he tried once more, and this time there was no turning back. He joined the North West Mounted Police and was stationed at Fort Walsh, not far from the present town of Maple Creek, Saskatchewan. There was adventure in the air. The Sioux, who had moved into Canada under Sitting Bull following the Custer massacre, posed a constant threat. The Blackfoot bands and their traditional enemies, the Crees, were held in uneasy check. Those curious geological formations known as the Cypress Hills, a spur of authentic desert complete with cacti and rattlesnakes, lay just to the south – the scene of a notorious massacre of Indians by Yankee traders. Most important of all, it seemed likely that a railroad would soon be pushed across the parched coulees directly into the heart of the mountains.

In April of 1881, when it became clear that a private company was actually embarked on the

CPR’S

construction, Wilson could stand it no longer. He had to be part of the action, and so he wangled a discharge, made his way south with a freight outfit, and reached Fort Benton, Montana, one week before Major Rogers’s survey crew – a hundred men in all – disembarked from the steamer. He was the youngest man to be hired by Rogers’s deputy, a stickler of a civil engineer named Hyndman.

The surveyors, whose task it was to find a route through the southern mountain chains, had come by way of the United States because that was the only existing route leading to the Canadian foothills. The traffic moved

north and south between Fort Benton and Fort Calgary as it would until the coming of the railway confirmed the lateral shape of the new Canada. The only evidence of an international border was a small cairn of stones placed along the wagon trail. The customs office was at Fort Benton, and the customs officer had only one question for travellers moving into British territory: “Got any T&B tobacco?” He was not interested in collecting duty – the distinction between Canadian and American territory was too hazy for such formalities; it just happened to be his favourite brand and it was hard to come by.

It took three weeks for the I. G. Baker Company, the pioneer border freighters, to shepherd the survey party to the site of Old Bow Fort in the shadow of the Rockies. There were nine prairie schooners drawn by twenty-four teams of horses together with eighty pack animals strung out across the coulee-riven prairie. Most of the men walked the entire distance.

It was unsettled country, populated largely by roving bands of Indians – Blackfoot, Piegans, and Bloods – and the occasional trader, priest, and Mounted Policeman. The wagon train wound through Coalbank, the site of the future town of Lethbridge, and crossed over the Oldman River, then in turbulent flood. Nick Sheron, a white pioneer who dug the coal from the banks in his spare time and shipped it south, ferried the men and supplies across. The wagons had to be converted into boats, the canvas lashed around the boxes, the running gear secured by strong ropes. The horses and ponies swam beside the wagons.

At Fort Macleod, the Mounted Police post, the party encountered Dr. George M. Dawson, the hunchbacked assistant director of the government’s Geological Survey, whose name would later be given to the most famous of the Klondike mining camps. The next settlement, High River, consisted of a single log trading post. Fort Calgary was slightly more pretentious: here were four log buildings – police barracks, mission, Hudson’s Bay post, and I. G. Baker store – and here “all went merry until midnight.”

Hyndman, the engineer in charge, was a puritan and a disciplinarian. He had, before leaving Fort Benton, drawn the attention of the party to a list of strict rules that were promptly dubbed “Hyndman’s Commandments.” Three aroused the special ire of the men:

- *Not a tap of work to be done on Sunday.

- *Men caught swearing aloud to be instantly discharged.

- *Men caught eating, except at the regular camp meal, to be instantly discharged.

When the party left Fort Calgary and camped at Big Hill Creek (the present site of the town of Cochrane), Hyndman’s rule against eating between meals was broken by two surveyors who caught and cooked a mess of fresh trout. Hyndman fired both of them, thus precipitating the first strike in Alberta. The party refused to move until the men were reinstated, and the resultant deadlock lasted two days until the transport boss suggested the matter be settled by the higher authority of Major Rogers, who was to meet them at Bow Gap.