The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (23 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

White immediately occupied a 160-acre homestead near the banks of the river where the survey line crossed it. This was to be the exact site of the business section of Regina, but to White it looked so desolate that he could not believe anyone would be foolish enough to locate a capital city on that naked plain. He relinquished his homestead and took up another two miles away, thereby depriving himself of one of the most valuable parcels of real estate on the prairies.

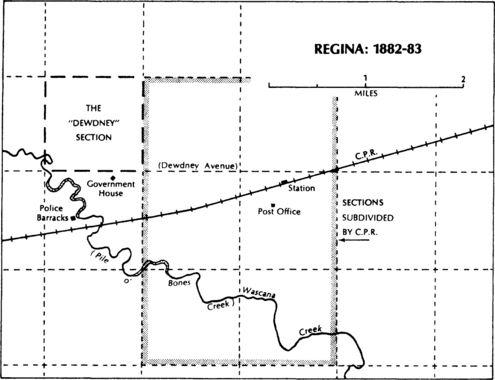

By this time rumours were flying in the Qu’Appelle Valley about the choice of a new capital. More tents were rising. At the Fort, the speculators were keeping a careful watch on Dewdney’s movements. It was not expected that he would leave the community during the Dominion Day festivities; a considerable celebration had been arranged at which, it was felt, the Lieutenant-Governor would have to be present. Dewdney took advantage of this conviction to slip quietly away. Late in the afternoon of June 30 he posted a notice near Thomas Gore’s tent reserving for the government all the land in the vicinity. The syndicate property, in which he had an interest, adjoined the government reserve directly to the north.

Thus was the city of Regina, as yet unnamed, quietly established. At Fort Qu’Appelle, when the news came, there was anger, frustration, disappointment, and frenzy. Most of the settlers hitched up their teams and moved themselves and all their worldly goods to the bank of Pile o’ Bones Creek.

Though it would require the sanction of the

CPR

, it was almost a foregone conclusion that this was the site of the new capital. Squatters, “advancing, like an army with banners,” began to pour towards the embryo city. Few of them were bona fide homesteaders. Dewdney reported to the Prime Minister, four days after the site was chosen, that most of them were paid monthly wages by Winnipeg speculators to squat on land and hold it “until it is found out where the valuable points are likely to be.…” By fall, the squatters, mainly young professional men – lawyers, engineers, clerks, and surveyors – held most of the available homestead land in the area of both Pile o’ Bones and Moose Jaw Bone creeks. Their “improvements” under the homestead law consisted of putting up a small tent or a log framework four or five feet high which was called a house. As Dewdney described it, “when a settler comes along looking for a homestead he is met by these ruffians who claim it.…” Genuine settlers, who were supposed to get homesteads for nothing, found themselves paying up to five hundred dollars for them. The speculators used a variety of devices to swindle the newcomers. One method was to use a bogus lawyer to confuse settlers about their pre-emption rights to quarter sections adjacent to their homesteads. If that failed, Dewdney noted in an interview that fall, “a revolver is produced.”

The matter of the capital was settled on August 12, though it was not so designated officially until the following March. Stephen arrived in Winnipeg, met Dewdney, and informed the Prime Minister by wire that he had agreed to the site of the new capital and had fixed on Assiniboia

as the appropriate name. Macdonald demurred; Assiniboia was already the name of the provincial district, established during the previous session. He suggested that the Governor General be consulted. For a while it seemed that the city would be named Leopold after the Queen’s youngest son, but this too was rejected. Lord Lorne left the matter to his wife, Princess Louise, and she chose Regina in honour of her mother.

The new name produced an instant, adverse reaction. Princess Louise was not the most popular chatelaine that Rideau Hall had known; her boredom with the capital was the subject of public comment. Nor was the Governor General immune from the political mudslinging that enlivened the period. The comment of the Manitoba

Free Press

, which was typical, might easily have been characterized as lese-majesty in a later and more reverent era:

“… the Governor-General … after harassing his massive intellect for a few days, evolved the word Regina from the chaos of his thoughts, and now the aforesaid capital will go down to posterity under the aegis of that formidable cognomen. From the foregoing fact we infer that His Excellency is not a success at christening cities.… Regina … is enough to blight the new city before it gets out of its swaddling clothes. If we have to put up with such outrageous nomenclature, it would have been better to stick by the old stand-by, Pile of Bones.”

The

Sun

queried a number of leading Winnipeggers on the subject of the name a few days after it was made public in late August. “Regina!” cried Joseph Wolf, the portly auctioneer, “well, that’s a fool of a name. Some old Indian name, musical to hear and pleasant to read of, conveying some poetical allusion to the spot, would have been just the thing.” Another leading citizen, Fred Scoble, referred bluntly to the new title as “a double-barrelled forty-horse-power fool of a name.” A third, John Peter Grant, insisted on calling the city “Re-join-her!” “Pooh,” he declared. “No name at all. Too effeminate altogether. The Marquis must have been thinking of the Princess’ frequent absences when he thought of that name. A city must be of the masculine persuasion to be of any use on general principles.”

The choice of the site provoked even greater controversy than that of the name. The press indulged in what the Edmonton

Bulletin

described as a “terrible onslaught” against the new capital. Some of this resulted from a Canadian Press Association visit to the townsite in August. The eastern reporters, used to the verdant Ontario countryside, were dismayed to find nothing more than a cluster of tattered tents, huddled together on a bald and apparently arid plain. They were also influenced by Major J. M.

Walsh, in charge of the Mounted Police detachment at Qu’Appelle, who did not like the choice of the new site and made no secret of it. Walsh greeted the newspapermen and their families in spectacular fashion, concealing a strong force of Mounted Police in the woods near Qu’Appelle and breaking cover just as the train puffed up the grade. To the shrieks of the engine and the cheers of the passengers the Major and his troop galloped alongside the track and escorted the entourage towards the new settlement on the Wascana, which Walsh then proceeded to condemn to the reporters. Walsh’s motives appeared to be as suspect as Dewdney’s since he had land interests at Qu’Appelle and, according to the Lieutenant-Governor, had “attended more to his land speculations … than to his Police duties.…”

Dewdney was convinced that Walsh was one of the chief reasons why the press turned almost en masse against Regina. The London

Advertiser

called it a “huge swindle.” The Brandon

Sun

said it should have been named Golgotha because of its barren setting. The Toronto

World

declared that “no one has a good word for Regina.”

Early visitors were astonished that such a bleak plain should have been preferred over the neighbouring valley. Beecham Trotter, the telegraph construction man, stringing copper wire across it early in July, thought of it as a lifeless land: “… there was not a bush on which a bird could take a rest.… Water was invisible for mile after mile.” One of Trotter’s companions remarked that a touring rabbit would have to carry all his lunch with him. “If anybody had told us that the middle of this billiard-tabled, gumboed plain was the site of the capital of a territory as big as France, Italy and Germany, we would have thought him daft.” Stavely Hill, the itinerant British politician, recorded that the site, as he encountered it in 1882, “was as little fitted for a capital city as any place could well be conceived to be.” Marie Macaulay Hamilton, who arrived as a child, remembered the embryo capital as “a grim and dismal place”; to Peter McAra, who later became its mayor, Regina was “just about as unlovely a site as one could well imagine.” Even George Stephen, who had picked the location sight unseen, was dubious after he visited it. “I hope Dewdney is right about Regina,” he wrote to Macdonald in September, “but, I ‘hae my doots.’ ”

*

Stephen would have preferred Moose Jaw.

Dewdney stuck to his stated conviction that he had chosen the best possible location. He publicly declared that the site had been selected because “it was by all odds the most favorable location for a city on the main line of the Canada Pacific … it was surrounded by the best soil, it has the best drainage, and the best and greatest volume of water, of any place between the Assiniboine and Swift Current Creek.” He told Macdonald, quite accurately as it turned out, that the new capital was in the very heart of the best wheat district in the country.

In the light of Dewdney’s personal interest in Regina real estate (at 1882 prices, he and his partners stood to make a million and a half dollars from their property if they could sell it) these statements were greeted with jeers, especially in the Opposition newspapers, which smelled another Conservative scheme to enrich the Government’s supporters through the building of the railway.

“It is intolerable that the high official whose prerogative it is to locate a capital city should have the privilege of first buying up the site in order to speculate in corner lots,” the

Globe

cried. Dewdney, of course, was only one of many public officials in both parties who were speculating in western lands, often with inside knowledge. “Suppose he did speculate in land or what not!” said the Fort Macleod

Gazette

of Dewdney. “Is not everyone from the highest to the lowest doing the same?”

The rest of the press was not so lenient. Dewdney protested to John A. Macdonald that his interest in the Regina syndicate was a small one and that he had a much larger share in land at the Bell Farm, Indian Head, a site he had rejected as a capital. Even the friendly Winnipeg

Times

could not stomach the obvious conflict of interest. Dewdney might say that he held the land not as lieutenant-governor but as plain Mr. Dewdney, but “it is impossible, however, to distinguish between the two entities more especially as Lieutenant Governor Dewdney and Mr. Dewdney have a common pocket.”

Dewdney’s Regina interests inevitably led to a clash with the

CPR

. The railway was already hard pressed for funds. Its main asset was the land it owned on the sites of new towns. It did not intend to share these real estate profits with outsiders.

In Regina, the railway’s interests were identical with those of the government, which was also in the land business. Under the terms of the contract, the

CPR

had title to the odd-numbered sections along the right of way, save for those originally ceded to the Hudson’s Bay Company. In Regina and in several other important prairie towns, the government and the

CPR

pooled their land interests, placed them under joint management,

and agreed to share the profits equally. That summer the railway, in order to raise funds, agreed to sell an immense slice of its land – five million acres – to a British-Canadian syndicate, the Canada North-West Land Company, for $13,500,000. The syndicate’s job was to manage townsite sales in forty-seven major communities, including Moose Jaw, Calgary, Regina, Swift Current, and Medicine Hat. The railway was to receive half of the net proceeds of these townsite sales. Thus, in Regina, one quarter of the land profits went to the railway, one quarter to the land company, and one half to the government.

The townsite property was held in trust by four men, Donald A. Smith and Richard Angus for the

CPR

and Edmund B. Osler, the Toronto financier, and William Scarth for the land company. Scarth was a loyal Tory and close friend of the Prime Minister (“your devoted follower from my boyhood”). Since he was resident in Regina, it was he who managed the townsite; and since, in Stephen’s phrase, the land company was “practically a branch of the Land Department of the

C.P.R

.,” the railway controlled all of the Regina land save for that held by the Dewdney syndicate.

A struggle now ensued between Scarth and John McTavish, the

CPR’S

land commissioner, on one side and Dewdney on the other over the exact location of Regina’s public buildings. The former wanted the nucleus of the new capital on the railway- and government-owned sections; Dewdney wanted it on his property. Both sides, in their many submissions on the subject, pretended that they had the future interest of the community at heart. (“McTavish … is trying to induce me to build in a locality most undesirable in order to bring the town in the direction he wants,” Dewdney complained to Macdonald in August.) But Regina was the product not of careful town planning but of commercial profiteering.

In the real estate contest that followed the railway held most of the cards. Its trump was the arbitrary location of the station two miles east of the Dewdney river property in a small and muddy depression far from any natural source of water. Dewdney was beside himself: “… in the spring it will be a mud hole,” he complained to Macdonald. It was “imperatively necessary in the interest of the City” that a change be made. But the

CPR

had no intention of making a change; although Regina began, at first, to grow up on two locations, the magnet of the station was too much for the settlers, whose tents started to rise in clusters on the swampy triangle known as The Gore in front of the makeshift terminus.

In October, the survey of the new capital was completed and lots put up for sale. The survey included everything but the Dewdney syndicate’s property on Section 26, Township 17, Range 20. Nonetheless, the owners

of Section 26 subdivided their land and put it up for sale as well. The struggle between Dewdney and Scarth moved to Winnipeg, where the rival properties were “boomed,” as the phrase of the day had it, in huge competing advertisements.