The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (27 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Hill liked to study men thoroughly, in the same way he studied transportation, fuel, or the works of Gibbon. Undoubtedly he knew a good deal about Rogers’s background – that he had gone to sea as a youth, that he had begun his adult life as an apprentice to a ship’s carpenter, that he had studied engineering at Brown University and then entered Yale as an instructor. Though Rogers was a Yale graduate, with a bachelor’s degree in engineering, it is quite impossible to think of him as a “Yale man,” with everything that phrase connotes. In a profession remarkable for its individualists, he was unique. He was short and he was sharp – “snappy” was an adjective often used to describe him – and he was a master of picturesque profanity. Blasphemy of the most ingenious variety sprang to his lips as easily as prayer to a priest’s. Because of this he was saddled with a variety of nicknames, such as “the Bishop” and “Hell’s Bells Rogers.” The young surveyors who suffered under him generally referred

to him as “the old man.” He was fifty-two when he set off into the mountains, but he must have seemed more ancient than time – a crotchety old party, seemingly indestructible and more than a little frightening. Small he may have been, but his mien was forbidding: he possessed a pair of piercing eyes, blue as glacial ice, and a set of white side whiskers that were just short of being unbelievable; they sprouted from his sunken cheeks like broadswords, each coming to the sharpest of points almost a foot from his face.

He had won his military title by displaying a quick mastery of bush-fighting in the Sioux uprising of 1861 and gained his professional reputation as “the Railway Pathfinder” while acting as a locating engineer for the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad. In the field he carried a compass, an aneroid barometer slung around his neck, and very little more. Generally he was to be seen in a pair of patched overalls with two pockets behind, in one of which he kept a half-chewed plug of tobacco and in the other a sea biscuit. That, it was said, was his idea of a year’s provisions.

The tobacco he chewed constantly. Secretan, who did not care at all for Rogers, paid tribute to him as “an artist in expectoration.” There were many who believed that he was able to exist almost entirely on the nutritive properties of chewing tobacco. “Give Rogers six plugs and five bacon rinds and he will travel for two weeks,” someone once said of him. Everyone who worked for him or with him complained about his attitude towards food; he was firmly convinced that any great variety – or even a large quantity of it – was not conducive to mental or physical activity.

His own diet was supremely Spartan: Harry Hardy of Chatham, who worked with him in 1883, recalled that “he was stingy with the Company’s money, but generous to a fault with his own.…I have heard it said that he carried raisins to eat with him on his trips. There were no raisins in the country. It was beans – just ordinary beans – that he carried. He used to eat them raw.” A. E. Tregent, who was with him that first year in the mountains, agreed: “His idea of a fully equipped camp was to have a lot of beans. He would take a handkerchief, fill it with beans, put a piece of bacon on top, tie the four corners and then start off.” John F. Stevens, who worked for him as an assistant engineer, described Rogers as “a monomaniac on the subject of food.” The Major once complimented Stevens on the quality of his work but then proceeded to qualify his remarks by complaining that he “made a god of his stomach.” Stevens had dared to protest about the steady diet of bacon and beans which, he said, were the camp’s

pièce de résistance

three times a day. His demands

for more varied fare marked him in Rogers’s eyes as an “effeminate gourmet.”

Van Horne tried constantly, and with only intermittent success, to get Rogers to provide more appetizing food in larger quantities for his men. On one occasion, while visiting his camp, he challenged the Major on the subject.

“Look here, Major, I hear your men won’t stay with you, they say you starve them.”

“ ’T ain’t so, Van.”

“Well, I’m told you feed ’em on soup made out of hot water flavoured with old ham canvas covers.”

“ ’T ain’t so, Van. I didn’t never have

no hams!”

Van Horne, so the story has it, moved hurriedly on to James Ross’s mountain camp where plenty of ham was available. It is small wonder Rogers had trouble keeping men working for him.

Outwardly he was a hard man – hard on himself and hard on those who worked for him. Only a very few, who grew to know him well, came to realize that much of that hardness was only an armour that concealed a more sensitive spirit. “Rogers was a queer man,” A. E. Tregent remembered, “lots of bluff and bluster.” It was a shrewd assessment. The profane little creature with the chilly eyes and the rasping voice was inwardly tormented by intense emotions, plagued by gnawing doubts, and driven by an almost ungovernable ambition. “Very few men ever learned to understand him,” his friend Tom Wilson wrote of him. Wilson, a packer and later a Rocky Mountain guide, was one of those few. Rogers, he said, “had a generous heart and a real affection for many. He cultivated a gruff manner to conceal the emotions that he seemed ashamed to let anyone sense – of that I am certain. His driving ambition was to have his name handed down in history; for that he faced unknown dangers and suffered privations.”

James Jerome Hill understood those ambitions when he offered to put Rogers in charge of the mountain division of the

CPR

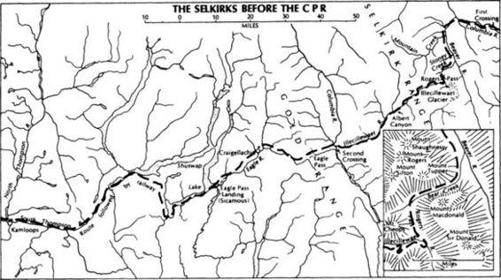

. Rogers’s main task would be to locate the shortest practicable route between Moose Jaw Bone Creek, west of Regina, and Savona’s Ferry in British Columbia, where Andrew Onderdonk’s government contract began. That meant finding feasible passes through the southern Rockies and also through the mysterious Selkirks. There were several known and partially explored passes in the Rockies, including the Vermilion, Kootenay, Kicking Horse, and Howse, but no one had yet been able to find an opening in the Selkirk barrier. Hill made Rogers an offer he knew he could not refuse: If the Major could find that pass and save the railroad a possible hundred and

fifty miles, he promised, the

CPR

would give him a cheque for five thousand dollars and name the pass after him.

Rogers did not care about the cash bonus. But to have one’s name on the map! That was the goal of every surveyor. He accepted Hill’s offer on the spot and, from that moment on, in Tom Wilson’s words, “to have the key-pass of the Selkirks bear his name was the ambition he fought to realize.”

Rogers’s first move was to read everything that was available about the mountain country, including the journals of Walter Moberly, a man who knew more about the Selkirk mountains than anyone alive. In 1865 and 1866, and again in the winter of 1871–72, this tough, dedicated, and often difficult engineer had sought a pass in the Selkirks without success. He had come to believe that none existed, but there was one possibility that he had not fully pursued. That was the east fork of the Illecillewaet River, a foaming tributary of the Columbia whose smoke-blue waters tore down the western wall of the Selkirks through jungles of spruce and cedar to join the mother river at the site of what is now Revelstoke, British Columbia.

An entry in Moberly’s journal of 1866, published by the British Columbia colonial government, caught Rogers’s eye:

“Friday, July 13th

– Rained hard most of the day. Perry returned from his trip up the east fork of the Ille-cille-waut River. He did not reach the divide, but reported a low, wide valley as far as he went. His exploration has not settled the point whether it would be possible to get through the mountains by this valley but I fear not. He ought to have got on the divide, and his failure is a great disappointment to me. He reports a most difficult country to travel through, owing to fallen timber and underbrush of very thick growth.…”

Perry was Albert Perry, known as the Mountaineer. Rogers was not able to interview him for he had died under rather gaudy circumstances. A man who hated Indians, he had often predicted that one would eventually murder him. One night, while Perry slept in his blankets under a tree near Burrard Inlet, an Indian made good that prophecy.

It is possible that Rogers did go up to Winnipeg, a day’s journey from St. Paul, to talk to Moberly, though it is doubtful he learned much more since Moberly had clearly rejected the Illecillewaet as a feasible route for the railway. Five years after Perry’s abortive foray, Moberly returned to the mountains on the Canadian Pacific Survey; he crossed the Selkirks on foot in midwinter but did not bother to explore the neglected valley, which

his earlier journal entries had suggested would bear further scrutiny. Indeed, he reported to the chief engineer, Sandford Fleming, that there was no practicable pass in that mountain rampart.

Nonetheless, Rogers determined to complete Perry’s exploration. With his favourite nephew, Albert, he set off at the beginning of April for Kamloops, the settlement closest to the Selkirks, which lay one hundred and fifty miles to the east beyond the intervening Gold Range. It took him twenty-two days to reach the town, for he had to travel by train to San Francisco, by boat to Victoria and New Westminster, and by stagecoach the rest of the way. When he arrived, he engaged ten “strapping young Indians” through a remarkable contract made with their leader, Chief Louie. Its terms rendered them up to Rogers as his virtual slaves, to work “without grumbling” until they were discharged. If any of them came back without a letter of good report, his wages were to be forfeited and the chief agreed to lay one hundred lashes on his bare back. The Indians were all converted Christians, but the local priest did not complain about this barbarism; rather he was a party to it, for he was the man to whom the letters of good report were to be addressed, and his church was to be the beneficiary of the forfeited wages. It is perhaps unnecessary to add that, in spite of the hardships the party encountered, no murmur of complaint ever escaped the Indians’ lips.

Rogers, who knew about three hundred words of Chinook jargon, the traders’ pidgin tongue, did not have a very high opinion of Indians, possibly because they ate too much – a fatal weakness in his eyes. “Every Indian,” he once declared, “is pious and hungry. Their teachings and their stomachs keep them peaceably inclined. Any one of them can out-eat

two white men, and any white man can out-work two Indians.” The Major spent eight days in Kamloops trying to find out how far an Indian could travel in a day with a hundred-pound pack on his back and no trail to follow, and how little food would be required to keep him alive under such conditions. He concluded – wrongly, as it turned out-that the expedition’s slim commissariat could be augmented by game shot along the way and so set off with a minimum of supplies. He was to regret that parsimony.

The twelve members of the party left Kamloops on April 29. It took them fourteen days of hard travel to cross the rounded peaks of the Gold Range (or Monashees as they were later called). They proceeded down the Columbia by raft, with the unfortunate Indians swimming alongside, until, about May 21, they reached the mouth of the Illecillewaet. Here Rogers found himself standing on the exact spot from which Moberly’s assistant, Perry, had plunged into the unknown, fifteen years before.

It must have been a memorable moment. The little group, clustered on the high bank of the Columbia, was dwarfed by the most spectacular mountain scenery on the continent. Behind them the rustling river cut an olive path through its broad evergreen valley. Above them towered the Selkirks, forming a vast island of forest, rock, ice, and snow – three hundred miles long – cut off from the rest of British Columbia’s alpine world by two great rivers, the Kootenay and the Columbia. These two watercourses, rising within a mile and a quarter of each other, together described a gargantuan ellipse which virtually encircled the mountain chain. The Selkirks, as Rogers probably knew, were of a different geological age and structure than the neighbouring Rockies; their distinctive shapes helped to tell that story – massive, cloud-plumed pyramids bulking against the sky. Once they had formed the crest of the continent’s spine, rising high above the prehistoric ocean, eons before the Rockies were born. It was only after the earth’s crust cooled and inner convulsions shifted the position of the continental divide that the Selkirks were subordinated to the younger peaks.

Now began a terrible ordeal. Each man balancing a hundred-pound pack on the back of his neck struggled upward, picking his way over mud-falls, scaling perpendicular rock points, wading through beaver swamps dense with underbrush and the “villainous devil’s clubs,” whose nettles were almost inescapable. Albert Rogers later wrote that without the fear of his uncle’s dreadful penalty, all the Indians would have fled. Recalling the journey two years later, Rogers remarked that “many a time I wished myself dead,” and added that “the Indians were sicker than we, a good deal.”

In the gloomy box canyon of the Illecillewaet (later named for Albert Rogers) the snow was still several feet deep. Above them, they could see the paths of the avalanches – the timber crushed to matchwood in swaths hundreds of feet wide. Sometimes, unable to move farther on one side of the river, they were forced to crawl gingerly over immense snow bridges suspended one hundred and fifty feet above the frothing watercourse. At this point, the toiling men, bent double under the weight of their packs, were too concerned with the problems of terrain to marvel greatly at the beauty around them; that luxury would have to await the coming of the railway. But there was a touch of fairyland in those shadowed peaks. The music of running water was everywhere, for the torrents of spring were in full throat. Above them they could catch glimpses of an incredible wedge-shaped glacier, hanging like a jewel from the mountain pinnacles. Before many years passed the Illecillewaet Glacier would become one of the

CPR’S

prime tourist attractions.